With Trump determined to have another US presidential run, the far-rights have been tasting electoral success in different parts of the trouble-torn world in recent times. Voters in the heart of Europe – especially in Italy and Sweden – veering to the far-right in the last couple of months have raised many eyebrows. Although staunch Brazilian leader Bolsonaro has missed out on his presidential re-election only by a whisker in the October 30 runoff, Israel’s ultra-nationalist leader Netanyahu has staged a historic comeback to form a far-right government, thereby raising a chorus of growing global concern – Is liberal democracy under threat with the rise of the far-right? NASHIR UDDIN digs deeper into the domain of far-right forces for this cover story

Although far-right extreme candidates have struggled in the November 8 US midterm elections, ultra-nationalist former US President Donald Trump has set his sight on yet another presidential campaign race lately. Meanwhile, his ardent follower and Brazil’s populist President Jair Bolsonaro has challenged the results of the October 30 second-round election runoff after apparently missing out on his re-election by a whisker, but voters in Europe have veered to the far-right in recent months as evidenced in the electoral success of Giorgia Meloni in Italy, Jimmie Åkesson in Sweden and Marine Le Pen in France.

You can also read: Rishi Sunak: Golden era of UK-China relations is over

One might argue that far-right French candidate Le Pen lost her race against President Emmanuel Macron earlier this year, but she remarkably got more than 41% of the vote in a runoff, far more than she got in 2017 polls, which suggests that her anti-immigration voice is being growingly heard in France.

In fact, there is a lot of evidence that far-right politicians have been gaining ground in recent years across different parts of the world. In Europe’s Hungary and Poland, more entrenched far-right leaders have already won and kept power. In a more dramatic fashion, the latest return of Israel’s longest-serving leader Benjamin Netanyahu to form a far-right government has only added further gloss to globally growing influence of the far-right politicians.

IS THE FAR-RIGHT A GLOBAL PHENOMENON?

As the far-right landscape is growingly getting global, virtually all countries have a potential breeding ground for far-right politics, which now stretches to places that have long been considered ‘immune’ to it, like Portugal, Ireland, Canada, and, until recently Spain. What’s more, the far-right landscape goes on way beyond the periphery of Western Europe and covers almost all corners of the globe these days. Political analysts say far-right’s salience in Central and Eastern Europe grew considerably throughout the 2000s.

Additionally, the far-right forces have both a historical and contemporary presence in Latin America and in the Global South, in countries like Turkey, Indonesia, Myanmar, and India, as well as in developed countries like the United States, Israel, Japan, South Africa, and Australia. Within this global scenario, the far-rights feature different variants of a shared ideological core, and invariably contain a multitude of organizations. The far-right politics, as we see, blurs the distinction between different modes of political partaking, as right-wing groups combine conventional party membership and un-conventional (if not violent) forms of politicking, extreme-right ideas and left-wing issues, as well as conventional imageries and pop culture symbols.

FACTORS AND PHILOSOPHIES CHARACTERIZING FAR-RIGHT SCENE

- The far-right is a global phenomenon with implications for local, national, and transnational politics.

- Far-right actors take on multiple organizational forms, have distinct political goals, and hold different understandings of democracy, nativism, and authoritarianism.

- The far-right politicians are against liberal democracy and prefer democracy of a more populist or authoritarian type.

- They very much often emphasise Christianity and the importance of Christian nationalism, as well as the role of the family.

- They openly campaign against what they call the LGBTQ lobby.

- The boundaries between the different geographic, ideological, and organizational variants of the far-right are often blurred.

FAR-RIGHT’S GEOGRAPHICAL SCOPE

The foremost political domain of the contemporary far-right groups is national domestic arenas. In most cases, the far-right actors run for national elections, organize around recognized national leaders, and mobilize on national values and top- ics. The exemplary example of these parties is the French Rassemblement National, or National Rally, un- der Marine Le Pen (previously Front National founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen), but more contemporary examples include Vox and its trailblazer Santiago Abascal in Spain, and Jair Bolsonaro’s Aliança pelo Brasil (Alli- ance for Brazil).

While domestic politics remains a primary channel of mobilisation, the far-right also informs supranational and transnational arenas. Political parties like National Rally and the Danish People’s Party, for instance, have taken advantage of supranational institutions like the European Parliament to build transnational links and partnership. In addition, recent years have brought about a revitalisation in cross-country mobilisation against migrants and refugees, via the swift spread of the pan-European Identitarian network, the emulation of the PEGIDA rallies outside of Germany, and the upswing of citizen street patrols following the Nordic model of the Soldiers of Odin. As a final point, certain far-right narratives, notably the white and male supremacism, have transcended national borders to become effectively transnational. Worldwide networks like the so-called ‘counter-jihad’ movement have especially benefited from the increasing availability of online spaces that allow for greater connectivity between far-right actors and Islamophobic individuals, which spans from Europe to North America to Asia.

Lastly, the far-right actors also take part in local and regional politics. Firstly, most of the far-right parties that are active at the national level also invest in local politics and community activism. Sub-national representation in the government may practically act as a ‘laboratory’ to test national campaigns and policy, as with the local councils regularly held by Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), and by the National Front in the French cities of Toulon and Orange in the 1990s. Secondly, certain far-right groups have emerged out of separatist movements (e.g., the Flemish nationalist Vlaams Belang, or Flemish Interest, and, up until recently, the Italian Lega (previously Lega Nord-Northern League) or at least politicized regional grievances (e.g., the French Identitarians, Shiv Sena in India, and CasaPound in Italy), with the goal of bringing these issues into the domestic political arena.

DOES GENDER PLAY ANY ROLE IN THE FAR-RIGHT?

- Gender dimensions have a role in far-right ideology in terms of embracing masculinity (for men) and femininity (for women).

- Although some far-right actors and organizations promote the idea of gender equality and are LGBTQ- friendly, most emphasize biological differences between men and women and traditional gender norms that fulfill these biological attributes.

- While most members of far-right organizations are male, women play critical roles as supporters, activists, or even sometimes as leaders, as well as symbols in far-right propaganda.

FAR-RIGHT ORGANIZATIONAL VARIANTS

The global far-right landscape comprises four main types distinguished by their degree of internal organisation and primary goals of action–ranging from the most structured and institutionally oriented to the least structured and grassroots-oriented ones. These platforms, on the one hand, can be non-hierarchical and leaderless, which is at odds with the foremost paradigm for the most far-right organisations. On the other hand, they allow for multiple forms of engagement, as the far-right groups and actors can readily manage web platforms, often in anonymous ways, and accordingly serve, at once, intellectual, militant, and information functions. The example of a successful far-right online mobilisation outcomes include the election of Brazil’s Bolsonaro, who has rather been grassroots-oriented.

THE FAR-RIGHT IDEOLOGICAL FEATURES

The far-right landscape ideologically comprises all actors that are located “to the right” of the mainstream and conservative right on the left-right political spectrum. The ideology of these groups rests on the belief that inequalities are natural and therefore some groups are superior to others, which informs their nativist and authoritarian views of the society. Almost all far-right groups see law and order (or order and punishment) as the crucial conditions to keep society together. Still, some quarters believe that developing a strictly ordered society can be possible only within a non-democratic, authoritarian regime, whereas others simply show authoritarian assertiveness, such as the glorification of authority figures, and the predisposition towards punishing any behaviour considered ‘deviant’ from their own moral values. In this respect, it is imperative to distinguish the diverse sub-variants of the far-right ideology.

It can be noted here that the pundits often distinguish between groups that are hostile to liberal democracy, usually referred to as the radical right, and those that oppose democracy as such usually referred to as the extreme right. Although radical right organizations are hostile to liberal democracy, they accept popular sovereignty and the minimal procedural rules of parliamentary democracy. Therefore, they seek to obtain support of the people by criticizing crucial aspects of liberal democracy, such as pluralism and minority rights, and also publicly condemn the use of violence as an instrument of politics. This perhaps is the most widespread variant of contemporary far-right ideologies, and applies to the most far-right parties represented in parliaments across Europe, including the Sweden Democrats and the Alternative fur Deutsch- land (AfD, or Alternative for Germany), as well as the Justice and Development Party in Turkey.

The extreme right organizations, by contrast, typically reject the minimum features of democracy -popular sovereignty and majority rule. They are often inspired by Fascism or National Socialism and believe in a system ruled by individuals, who have special leadership characteristics and are thus naturally different from the rest of the people. Consequently, they reject democracy and party politics, oppose all forms of ethnic and cultural diversity within the nation-state, and are open to the use of violence to implement political agendas. Modern-day examples of extreme right actors include the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn in Greece, the paramilitary organization Rashtriya Swayam-sevak Sangha (National Volunteer Organization) in India, and the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan in the USA.

In addition, researchers recognize two (or sometimes even three, as deliberated here) main variants of the nativist component of the far-right ideology, i.e., the idea that only native people shall reside in nation-states. Biological racism comes up as the first variant that suggests that specific ethnic groups are genetically greater to others, and it is predominantly endorsed by marginal extreme-right parties and white supremacist organizations promoting racial compassions of ethnic dominance. The second one is ethnic nationalism, which is supported by the majority of radical right parties that reject racial hierarchies in support of an ethnocultural understanding of the nation. Looking at the nation in terms of ethnicity, as well as shared cultural characteristics, like language, traditions, and religion, these groups argue that the mixing of different ethnic groups creates overwhelming cultural complicacies and should therefore be opposed. Unlike biological racism, this sort of nativism distorts dominant liberal values to challenge minority rights, religious pluralism, and ultimately, the im- migrants’ arrival and settlement in general.

The far-right ideology can also take new and often surprising forms if these ideological variants are growingly established. Across the world, the far-right groups draw progressively on themes and demands traditionally associated with the political left, like environmental protection and females’ rights. Far-right groups, associating these issues to their nativist and nationalist ideals, try to blur the distinction between the mainstream and the far-right politics. Repackaging the far-right perceptions in ways that resonate with more prevalent ideas and pop culture symbols, in fact, allows marginalized far-right groups to attract foreign media attention and impact mainstream politics.

TIES BETWEEN THE FAR-RIGHT AND THE MEDIA

- While established news media are often critical to far-right actors, they have several times played a vital role in mainstreaming far-right actors and their beliefs.

- Far-right actors often criticize “mainstream” media and communicate through alternative news media, as well as blogs, websites, forums, and mainstream social media platforms.

- Far-right actors were early adopters of digital communication technology and they are currently in the forefront of online “attention hacking” through aggressive speech, hate campaigns, memes, and dis/misinformation.

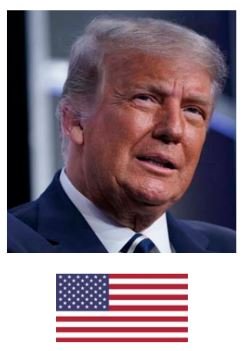

USA

The world has arrived at an historical inflection point few believed would be possible in countries such as the United States, which has long claimed the bragging rights as the world’s greatest democracy. The ascendency of the despotic Donald Trump and his administration that excelled at grooming the public for an embrace of fascism as sent chills throughout what’s left of the civilized world. As in many other countries, the far-right in the US found itself pushed to the margins in the aftermath of the Second World War. However, this process was neither straightforward nor definitive.

Trump’s candidacy and campaign in 2016 allowed for the different strands of far and extreme right to converge under one banner, as he was not only the candidate of the Grand Old Party, but also closely allied with the new kid on the far-right block: the alt-right. Trump also received support from traditional extreme-right movements and actors such as David Duke, a former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, and the Proud Boys.

ITALY

The hot-button issues like immigration, cost of living, and energy crises easily translate to Italy too, where like-minded far-right forces have been voted to power of late.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, which is known as an insurgent populist movement whose lineage traces back to Mussolini, has formed the incumbent government.

As the 45-year-old far-right political firebrand from Rome was sworn in as Italy’s first female prime minister on 22 October, she was backed by two more familiar rightwing figures, the ex-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and Matteo Salvini of the League, both of whom are deemed as expert in the politics of division.

Like the Sweden Democrats and Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly the National Front), the Brothers of Italy have carefully laundered their image and suppressed their wilder urges.

Meloni has moderated her anti-EU stance and distanced herself from Russia. In contrast, Berlusconi is known as an old pal of Vladimir Putin. Italy’s far-right shares other characteristics with European brethren–hostility to “elites”, authoritarian tendencies, disdain for multiculturalism and gender rights, and an obsession with national identity underpinned by racism.

PORTUGAL

Portugal until 2019 was touted as seemingly immune to far-right populism in the political arena, in stark contrast to other parts of Europe. But in Portugal’s January 2022 polls, the far-right party Chega made gains although the socialists got re-elected.

The far-right Chega (Enough) party made significant gains and was third with 7.15% of the vote. Earlier, far-right candidate André Ventura managed to secure over half a million votes to reach third place.

He was an MP and leader of Chega, a proto-fascist party which became a member of the European Parliament’s Identity and Democracy group in October 2019, just months after formation in April the same year.

Progressive forces in Portugal find themselves fighting a war on two fronts: a resurgent far right has been making inroads into the country’s politics, while the long-standing monopoly on power held by the parties of the “big centre” has stifled the voices of any genuine opposition.

In a society where the legacy of dictatorship and colonialism can still be felt, where racism remains rife, and ecological thinking has yet to take root, setting out a unifying political vision to take on these powerful rivals is far from simple.

SWEDEN

leader of the Sweden Democrats

The success of the Sweden Democrats in the September 11 national elections shows that no country is immune to far-right populist parties. As part of the scary rise of the far-right in Europe, it’s a familiar theme and one that progressive politicians and liberal media often rehearse. Voting behaviour in different countries is influenced by personalities, events, timing, regional issues, party loyalties and electoral systems. In the end, all politics is local.

That said, far-right populist parties are a pan-European problem that concerns all democrats. Common ground, and ideological conjunctions, can be found, for example, between Sweden, in Europe’s far north, and Italy in the Mediterranean south. In both, radical right parties are on the up. Surprising many in Stockholm, the Sweden Democrats, a party with neo-Nazi roots and a fierce anti-immigrant, law and order stance, won second place in the September 11 national election, backed by one in five voters.

Its support will be crucial for the new centre-right coalition aiming to replace the Social Democrats. If the fact that such a party, skewered by opponents as neo-fascist brown shirts, will play kingmaker is not alarming enough, then consider this: in the land of Greta Thunberg’s birth, 22% of first-time voters aged 18 to 21 voted for the Sweden Democrats, a party that shares the European far-right’s scepticism about the climate crisis. Worries about cost of living and energy crises, the war in Ukraine, immigration and gun crime–a burning issue in Sweden–may help explain this phenomenon.

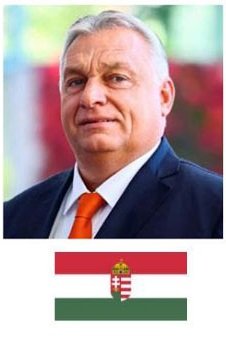

HUNGARY

The damage the far-right can do in power is painfully evident in Hungary. Its pro-Moscow prime minister, Viktor Orbán, and his Fidesz party have obstructed EU action on Ukraine and undercut judicial, academic, minority, and media freedoms. In September, the European parliament declared Hungary was no longer a democracy.

FRANCE

The electoral success of Germany’s centre-left Social Democrats, and setbacks for the hard-right Alternative for Germany in 2021, suggested the forces of reaction were in retreat.

Then came France’s presidential election run-off, when the far-right’s Marine Le Pen gained a record 13.3m votes. The far-right candidate in France, Marine Le Pen, lost her race against President Emmanuel Macron earlier this year, but she got more than 41% of the vote in a runoff, far more than she got in 2017, which suggests that her anti-immigration message is growing in France.

This startling change of fortunes must be ascribed, not just to a weak and divided left, but also to the growing European trend in anti-immigration attitudes. However, the broader lesson to be drawn from such fluctuations is that efforts to discern distinct, Europe-wide trends can be misleading.

POLAND

Poland’s president is Andrzej Duda, who narrowly won re-election in 2020 with a focus on anti-LGBTQ sentiment. Duda is another favourite of Trump’s.

The right-wing Polish Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, is another vocal white supremacist.

His ultraconservative ruling nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) hosted ‘Warsaw Summit’ of the far-right forces in December last.

BRAZIL

‘Bolsonarismo,’ the Brazilian far-right movement built around President Jair Bolsonaro, shares much in common with ultra-conservatives in power in Europe–Hungary, Poland, and Italy–but is closer to Donald Trump and the US alt-right. Although he challenged the results of October 30 second-round election runoff after apparently missing out on his re-election by a whisker, the far-right’s arrival in power in Brazil, as elsewhere, is linked to deep social upheaval.

In Europe, the far-rights accuse immigrants of causing every crisis and want to close the borders, but the Brazilian context is different: no longer a major immigration destination, “immigrants aren’t a big subject,” and Islamophobia and anti-Semitism are less prevalent than in Europe. Bolsonarismo’s version of “national solidarity” is instead a battle of “good people” versus the “corrupt.” As with far-right movements everywhere, Bolsonarismo’s Holy Trinity is God, country, and family.

The latter, says true believers, is under threat from gay marriage, abortion, and “gender ideology.” Whereas conservative Catholics are the core of the European far-right, in Brazil, it is the powerful, fast-growing Evangelical movement. Bolsonaro’s movement is also more military in nature than its European cousins.

UNITED KINGDOM

Britain’s two-party system excludes smaller, extreme parties from parliament. But they operate in more insidious ways. It is also true, as one might say, that far-right parties have not gained the significance in the UK that they have elsewhere.

The first-past-the-post voting system effectively excludes the representation of small, far-right parties in parliament. More effective, in Britain, is entryism into an existing party. The UK’s white supremacist British National party (BNP) is, however, highly unlikely ever to return an MP to Westminster – thanks partly to Britain’s electoral system.

It’s best ever electoral showing was at the local elections, in which BNP candidates won three local council seats (out of a national total of over 6,000) in the deprived and racially divided Burnley. The BNP’s Cambridge graduate leader, Nick Griffin, wanted to pay non-whites to return to their countries of ethnic origin.

He represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament from 2009 to 2014. Griffin served as chairman and then president of the far-right British National Party from 1999 to 2014, when he was expelled from the party.

However, the British should be grateful – and proud – that far-right parties have never gained the significance they have elsewhere – especially at a moment of national introspection and not a little self-flagellation – whereas Austria, Spain, the Netherlands, and Serbia all have their own versions of the same contagion. In fact, the far-right parties have been gaining ground in several European countries since the 1990s, their successes ascribed to disenchantment with the perceived failures of left-wing governments, growing concern over immigration, and the tightening of the European Union. A game-changing surge in support for nationalist, Euroscep- tic, culturally intolerant parties was predicted after the 2016 Brexit referendum and Trump’s US election victory. In fact, the rising assemblage of the far-right, associated with white nationalism, nativist ideologies, and identitarian politics, has established itself as a major political force in the West in the last decade – thereby making substantial election gains across the USA, Europe, and Latin America, and coalescing with the so-called populist movements of Trump, Brexit, and Boris Johnson’s 2019 polls in the UK. And this shift in political paradigm represents a major new political force in the western world that has rolled back the liberal international- ism that developed after WWI and shaped the world institutions, globalization, and neoliberalism. It also had an impact on western democracies. Analysts see its historic origins date from the rise of fascism in Germany, Italy, and Austria from the 1920s. Indeed, the movement can be conceived as a reaction against the rationalism and individualism of liberal democratic societies, and a political revolt based on the Nietzsche, Darwin, and Bergson philosophies that purportedly embraced irrationalism, subjectivism, and vitalism as the core. As for Europe, the 27-nation EU is already beset by challenges, including rising inflation and energy costs, and is now wary that a far-right Italian leader might join a strident nationalist bloc, including Hungary and Poland. The EU leaders will be watching to see if Meloni takes office at the heart of Europe as a populist firebrand, who rallies against the EU, or, as she has in recent weeks, toned down her rhetoric. In South Asia, critics are pondering an idea as to whether any rise of the far-right can take centre stage here. The answer that comes straightway is if the affairs are mismanaged here badly enough, yes, it could. The December 2021 meeting of the European far-right in Poland’s Warsaw.

“All these far-right movements are rooted in an economic and social crisis that is growing worse by the year: rising inequality, declining income for the working and middle classes,” says Christophe Ventura, a Latin America specialist at the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs (IRIS).

Exclusive Interview with Professor Bashir Ahmed

PROFESSOR BASHIR AHMED, Teaches politics at Jahangirnagar University’s Department of Government and Politics. He often appears in media as a pundit on governance and international issues as well. Recently, he talked to Press Xpress Joint Editor Nashir Uddin in an exclusive interview and shared his views on the scary global rise of the far-right.

- What is the reason behind the recent electoral success of the far-right across the world?

In my opinion, the traditional left-right socioeconomic split has somewhat faded over time, and the debate over open borders versus border closure has largely taken its place. Numerous academics have examined the traits and causes of supporters of far-right parties – noting the dangers they bring to liberal democracy. Far-right voters often resemble non-voters and conventional left-wing party supporters in terms of socioeconomic disadvantage, and they resemble center-right party supporters in terms of authoritarian ideas.

We need to look at how far-right candidates have done well in elections around the world, at the same time we should look at more subtle factors that may have contributed. It also considers the geopolitics of the various states, the integration of policies by opposition parties, specific events and their proximity to the various states, the growing trend of rejecting traditional electoral politics, the softening of opinions from hard-line racism to a focus on immigration levels and economics, and so on. As a result, success will be measured not only in terms of seats won but also in terms of other populist movements like street protests, online support, and lobbying influence – explaining why some far-right parties have been more successful in some countries than others.

- Does it signal any durable change in world’s governance order?

In the coming days, I can already sense a worrying shift in the global governing structure. Because of the electoral success of far-right candidates that pander to anti-immigrant sentiment and disregard basic civil and political liberties, difficulties inside democratic regimes have fostered the growth of populist leaders. In France, the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria, right-wing populists increased their support and parliamentary representation in 2017. Except for Austria, they were kept out of power, but their electoral success contributed to the demise of both left- and right-wing establishment parties.

While centrist newcomer Emmanuel Macron easily won the French presidency, major parties had trouble forming stable governing coalitions in Germany and the Netherlands. Consider the United States, which has suffered a string of failures in the administration of elections and the criminal justice system over the past ten years—under the leadership of both major political parties—but whose core institutions were attacked in 2017 by a government that rejects long-established standards of ethical behavior in a variety of endeavors.

- Do you think the recent far-right success stands as an apparent threat to the established democratic norms across world?

My belief is that the rise in antidemocratic measures around the world is more than just a set- back for fundamental liberties. There are dangers to the economy and to security. When there are more free nations, all countries, including the United States, are safer and more prosperous. As there are more authoritarian and oppressive regimes, alliances and treaties fall apart, nations and entire regions become unstable, and violent extremists have greater opportunities to operate.

Democratic regimes give citizens the opportunity to shape the laws that all must follow and to have a role in how their lives and jobs are conducted. This encourages a greater respect for harmony, justice, and accommodation. Unfortunately, due to the rise of the far-right, so-called autocrats impose arbitrary laws on their subjects while disobeying any restrictions themselves, which breeds abuse and radicalization.

- How do you regard the far-right action, influence and prospect in South Asia in general and Bangladesh in particular in the coming days?

It is true that democratic governance and South Asia have a tangled relationship. Widespread democratisation in the 1980s and 1990s changed the region’s character from its illiberal past and raised expectations for a democratic wave. But in recent years, democratic regress has turned the political tides against democracy, fuelling a rise in illiberalism and, in some circumstances, authoritarianism. Even the “successful” democracies in the region nevertheless struggle with issues of accountability and financial transparency.

In addition, there is growing political division along racial, ethnic, and religious lines in many Asian countries. As many times as not, governments have reverted to illiberal techniques and practices to quell dissent and support their own positions in an increasingly dangerous domestic political context. This is something that our political parties have emphasized. In many Indo-Pacific nations, illiberal trends have been intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic. South Asian nations have used widespread lockdowns, limitations on the freedom of speech and movement, and escalating policing powers. Even established democracies are being forced by the COVID-19 problem to address the issue of striking the right balance more explicitly between individual liberty and collective interests.

Many of the governments in South Asia have a lot of tough choices to make in figuring out how to best play the hand they have been given. The best way to promote the rule of law, human rights, and democratic government in a region that supports many democratic standards but is wary of ideological conflicts between China and the United States and their effects on South Asia will need to be decided among these factors.

It is too early to make any judgments on the far-influence rights on Bangladesh’s electoral process. Bangladesh will be an asset in the great-power conflict taking place across Asia since it is a sizable and developing nation in a strategically important area. As a result, Bangladesh and other South Asian nations’ party structures saw considerable transformations. The far-right has broken long-standing patterns of party competition by moving from the edges to the mainstream.