For the past 15 years, BNP and its alliance have remained outside the realm of political power. Following their defeat in the 2008 elections, their absence in the 2014 electoral process, and their inability to facilitate the 2018 elections, they opted for a path of protest and agitation. However, their efforts in various movements yielded no success. Instead, these movements often led to widespread chaos and distanced them from the general populace. This report delves into the reasons behind their consistent failures in these movements.

A regular turnover of ruling authorities can be beneficial for a country’s progress. However, when the alternative party fails to present an appealing vision for the nation, the idea of change for the sake of change loses its appeal among the populace.

BNP appears to lack a clear and defined ideology, making it a less compelling opposition force. While many political parties and groups in Bangladesh may be primarily clientelistic, they still retain some semblance of an underlying ideology. The ruling Awami League, for instance, seems to embrace a (nationalist) ideology, albeit adaptable, rooted in its historical role during the Liberation War.

In contrast, BNP has failed to establish a strong ideological foundation that could unite and attract the public. From its inception, it has been a mixture of disparate elements, lacking a coherent and appealing ideology. As a result, they have been unable to build a robust foundation among the people, leading to the lack of success in their movements over the past 15 years.

You can also read: ELECTION NEGOTIATION: WHY IS AWAMI LEAGUE TOUGH ON BNP?

BNP’s Movement Failed – Obaidul Quader

Obaidul Quader, the General Secretary of the Bangladesh Awami League and the Minister of Road Transport and Bridges, emphasized that BNP’s inability to succeed in the recent movement reflects a broader trend. He asserted that a party that fails in a movement is also likely to falter in an election, as those who cannot achieve their goals in movements often face similar setbacks in electoral contests. These remarks were made during his speech as the chief guest at a ‘Peace, Development, and Reconciliation Rally’ hosted by the Awami League.

Mirza Fakhrul’s Expression of Concern

Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, the Secretary-General of BNP, expressed his concern by remarking that the party’s inability to mobilize the youth for its movement represents a shortcoming. He made these remarks during a discussion meeting commemorating the 40th death anniversary of BNP’s founder and former president, Ziaur Rahman.

Mirza Fakhrul stated, “Across the world, historical changes have been driven by youth movements. However, where are our youth today? Our shortcoming lies in our inability to engage the youth. I firmly believe that we have yet to effectively involve the youth.”

Why BNP Faces Repeated Failures

A Retrospective:

The year 2022 marked a potential turning point for the primary opposition party, BNP, and its closely aligned partner, Jamaat-e-Islami. Several political factors appeared to be favoring BNP-Jamaat right from the outset. Early in the year, when Sri Lanka declared bankruptcy amid an economic crisis, a group of rumor spreaders began circulating false information on social media about similar impending consequences in Bangladesh.

Simultaneously, due to the economic sanctions imposed by Western countries on Russia following the conflict in Ukraine, global commodity and dollar prices surged, leading to a foreign exchange crisis within Bangladesh. The government was compelled to impose import controls and raise fuel prices, resulting in increased hardships for the public due to soaring prices of essential goods. This economic instability provided an opening for BNP and Jamaat after years of political dormancy.

The political landscape of BNP-Jamaat, which had largely receded to press conferences following their electoral setback in 2018, witnessed a resurgence. The alliance began advocating for the reinstatement of a caretaker government, a demand that had virtually faded away in 2018. BNP, in particular, successfully organized numerous public gatherings at the ward, union, and departmental levels by revitalizing dormant leaders and activists through various programs. Buoyed by these activities, the government found itself facing calls for a unified movement against it.

The return of Tarique Rahman from self-imposed exile in London, coupled with declarations by some senior BNP leaders that Khaleda Zia would take charge of the country from December 10, generated considerable buzz. However, as the year progressed, they refrained from making any definitive announcements and instead opted for a 10-point demand and a nationwide mass march on December 24. Nine days after the initial 10-point announcement, a 27-point announcement added further ambiguity to their objectives. By year-end, BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami once again found themselves ensnared in a political quagmire, leaving many questions about their true intentions unanswered.

Chaos Under the Guise of Protest:

This isn’t the first instance of political tumult involving BNP-Jamaat. In 2013, they attempted to obstruct the trial of war criminals by advocating for a transparent, impartial, and international justice system. Jamaat, operating under the political shelter of BNP, wreaked havoc across the nation for years, resulting in the loss of many innocent lives. Ultimately, they couldn’t obstruct the trial of those responsible for the 1971 atrocities, with several perpetrators already facing execution.

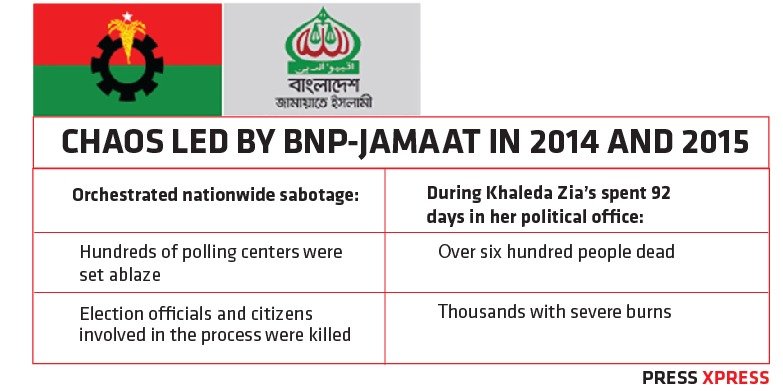

In 2014, the BNP-Jamaat alliance orchestrated nationwide sabotage to disrupt the 10th National Assembly elections. Hundreds of educational institutions designated as polling centers were set ablaze, and election officials and citizens involved in the process were killed. Their efforts fell short again as the elections proceeded on schedule, and a government was formed. BNP leader Khaleda Zia spent 92 days in her political office, vowing not to return home until the government fell in 2015. During these 92 days, the BNP-Jamaat alliance instigated widespread violence, leaving over six hundred people dead and thousands with severe burns.

Subsequently, militant organizations became increasingly active, targeting both local and foreign individuals, including common people, clergy, shrine attendants, writers, and publishers. Jamaat’s connections with various militant individuals and organizations had been proven repeatedly in the past and present. This raised concerns about potential collusion between BNP-Jamaat and militant groups, but their conspiracy failed once again as the Awami League government vigorously combated militancy.

As a result of their repeated failures in four successive anti-Awami League movements, the BNP-Jamaat alliance practically abandoned its demand for national elections under a caretaker government. However, in 2018, they adopted a new approach. Led by Dr. Kamal Hossain, a trusted figure in the Western world, they formed an alliance called the Jatiya Oikya Front and participated in the 11th National Assembly elections. Unfortunately, many BNP-Jamaat activists and supporters couldn’t reconcile with this ‘secular’ leadership. Additionally, rampant nomination trading occurred, resulting in multiple coalition candidates in most constituencies. This fragmented their election campaign and divided their activists. The Jatiya Oikya Front managed to secure only seven seats, five of which were from BNP and two from Ganoforum.

Dreadful Political Practices:

Despite BNP’s formation occurring after 1975, Ziaur Rahman established a cabinet that included individuals associated with the 1971 assassination and political middlemen. This move extended a political platform to all anti-liberation war parties, including Jamaat-e-Islami, Muslim League, and Nezam Islam, allowing them to engage in politics within independent Bangladesh.

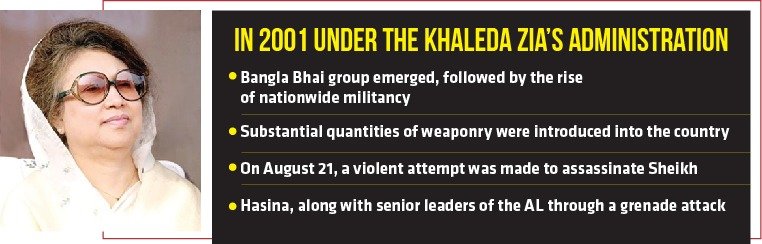

Similarly, Khaleda Zia, in 2001, formed a cabinet that included recognized war criminals. During her government’s tenure, a strategy was employed to suppress progressive and left-wing organizations. First, the Bangla Bhai group emerged, followed by the rise of nationwide militancy, all with the implicit support of the Khaleda Zia administration. Moreover, substantial quantities of weaponry were introduced into the country under the government’s supervision. On August 21, a violent attempt was made to assassinate Bangabandhu’s daughter, Sheikh Hasina, along with senior leaders of the Awami League through a grenade attack.

Leadership Shortcomings in BNP’s Setbacks:

The grassroots members of BNP hold the view that the party’s failures in anti-government movements are primarily attributed to its leaders. The leaders’ propensity to evade confrontation has hindered their ability to mobilize workers effectively. Even grand initiatives like the Democracy Movement failed to gain traction due to the lack of committed leadership. These sentiments were expressed by field workers who attended a recent BNP rally at Suhrawardy Udyan.

Many activists also believe that BNP’s reputation has suffered due to its association with Jamaat, with the blame for Jamaat’s terrorist activities falling squarely on BNP’s shoulders. One BNP worker expressed, “In politics, one must be prepared to endure imprisonment and persecution. How can a movement succeed if leaders shy away from the fear of arrest?” A youth party member questioned the effectiveness of leaders who only appear in front of television cameras but do not actively participate in the movement.

There are differing opinions on whether BNP has benefited or suffered from abstaining from elections. Some Trinamool activists within BNP believe that the party can regain power by removing the “failed and fugitive leaders” and reorganizing the party.

On the other hand, BNP’s student organization and its primary political wing lack experience in organizing movements, and it’s not in their nature to do so. They contend that they face obstacles, such as police restrictions on their activities and numerous legal cases filed by the Awami League against their leaders and activists, which consume their time and resources, making it difficult to engage in movements effectively.

What Could Have Been Done Differently

Looking back a bit, the pivotal moment for the BNP after 1991 was the opportunity to break away from its military legacy and transform into either a conservative or center-right democratic party. This chance presented itself in 1991 for various reasons. However, the BNP failed to seize this opportunity. Had the BNP chosen a different path and refrained from aligning with Jamaat on that day, the party might have lost power through a vote of no confidence in Parliament, similar to the first government of Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Yet, like Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the BNP could have reclaimed power by running an interim government and holding elections within a specified timeframe.

Despite being labeled a so-called religious nationalist party, the BNP had the potential to transform into a center-right political party rooted in country-based nationalism, rather than being associated with religious nationalism or carrying the legacy of war criminals and the military. If the BNP had won clean elections while managing the interim government, there would have been no need for forming an unelected caretaker government for a second time in Bangladesh. The nation could have progressed in the democratic process. Even if the Jatiya Party or Ershad had been rehabilitated, they would have left a lesser military legacy.

The focus should have been on a country-based approach rather than a religious-based one, reducing the chances of religiously fueled politics gaining prominence in the country. At that time, Awami League’s ideological struggle had a different context; it didn’t need to compete in the realm of religious nationalism or support for religion. The battle was between the Bengali nationalism rooted in a thousand years of Bengali culture and the country-based nationalism of the BNP and Jatiya Party. Awami League’s Bengali nationalism was primarily rooted in conceptual and traditional nationalism. The outcome in terms of vote politics and convincing the people was a separate matter.

In 1991, however, the BNP chose a different path by forming a government with the support of Jamaat-e-Islami and engaging in contentious elections. This decision, in part due to Jamaat’s influence, perpetuated the rise of religious-based politics in the country, along with the resurgence of demands for caretaker politics. The BNP lost out to the movement advocating for a caretaker government, ultimately leading to the Awami League’s return to power in Bangladesh after a span of twenty-one years.

Contrasting Approaches: AL vs. BNP in Political Movements

Those acquainted with the political history of Bangladesh and East Pakistan recognize that after August 15, 1975, Awami League leaders and workers faced numerous legal cases, far surpassing the current scenario. On that fateful day, many leaders from Awami League, Jubo League, Chhatra League, and Sramik League were detained. However, what set them apart was their resilience and adaptability. Even though their leaders were arrested, others stepped up to lead, and they conducted their movements with tactical precision, though not on a massive scale. Their primary goal was to overthrow the military government, and their unity and determination were evident.

In contrast, the reality of BNP’s last 15 years has been marked by an inability to articulate a coherent political program. This is not only a significant failure for a party with over four decades of existence but also evidence of its failure to evolve into a genuine political entity. In the realm of politics, it holds true across all nations that for any political party, whether it’s for elections or movements, the foundation lies in establishing a clear political agenda. Once the people embrace this agenda, the possibility of successful movements and political victories naturally follows. BNP, unfortunately, has not reached this crucial stage, and this political mediocrity remains at the heart of its failures.

Why has the BNP-Jamaat alliance struggled to regain political ground despite repeated efforts? Undoubtedly, these two forces have engaged in politics for many decades, drawing support mainly from religious sentiments, often with the backing of certain segments of civil society and without international repercussions. However, their return to the political mainstream has been hindered primarily by their reliance on non-political means. In essence, until BNP-Jamaat can distance themselves from opposition politics, militancy, and terrorism, their political reintegration remains elusive. Any temporary resurgence built upon non-political alliances is unlikely to be sustainable, as evidenced over the past decade and a half.