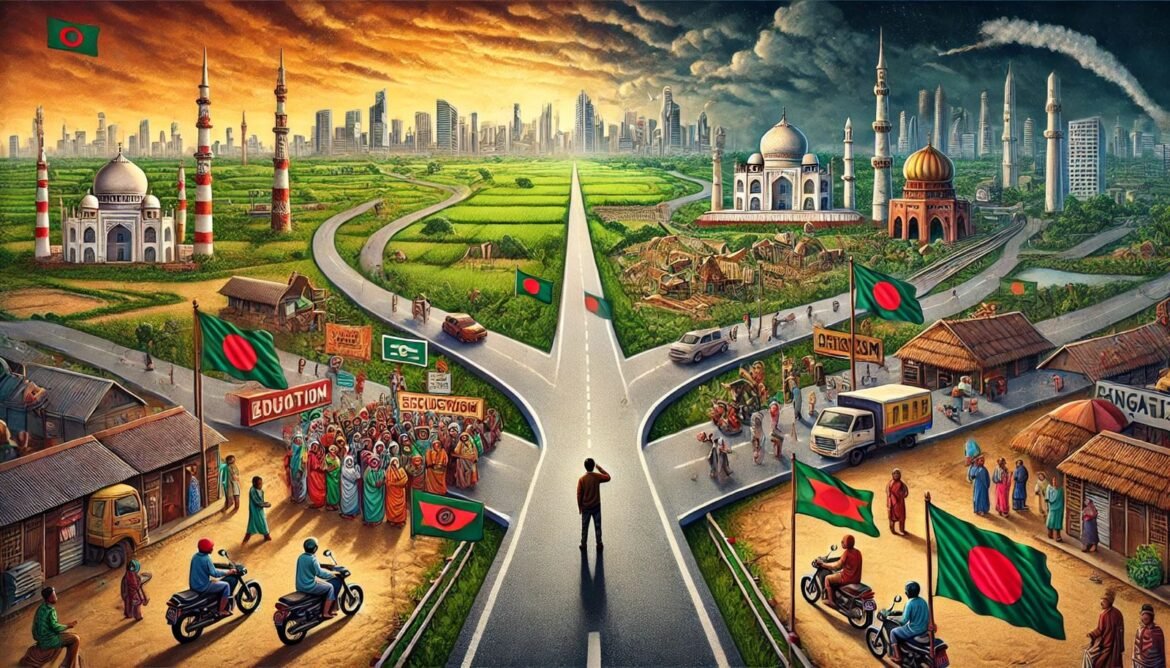

Bangladesh is at a critical crossroads amidst the complexities of political balance between the secular aspirations of its people and the rise of a strong Islamist movement. Professor Mohammad Yunus, the Nobel Laureate and head of the interim government, has been striving to restore normalcy in the country and bring back democratic values. On the other hand, Islamist elements want to inject transformation into their populous country for an Islamic state.

According to reports in The Daily Star and Dhaka Tribune, one of the most influential Islamist parties of Bangladesh, Jamaat-e-Islami, has recently held a pivotal meeting in Dhaka with key Qawmi scholars. The agenda, held on August 25, called starkly for the establishment of governance under Islamic law. This is not an effort by fringe elements but some of the most prominent members of this coalition, Hefazat-e-Islam, considered hardline and commanding influence over substantial elements of the population.

While Yunus has shied away from proclaiming his regime as “secular,” every one of his speeches has spoken to reforms, unity, and protection for minorities. It is in this light that he seemed to pledge to keep Bangladesh a democratic, eclectic state. Yet, this vow of his is now increasingly pitted against the forces that believe Bangladesh’s identity must be transformed into that of an Islamic republic.

Yunus is only beginning to develop his leadership, and his appointment as an advisor to the interim government has already received mixed responses. By many accounts, he is making “the right moves” by reaching out to religious minorities and calling for reforms in institutions, among other things. But there are more immediate tasks that his government needs to get its act together on, like flood relief and ensuring a free and fair election. Some ministers have been criticized for their efforts to shift blame on India for recent floods in the country. This has been largely viewed by critics as little more than a diversionary tactic, intended to deflect attention from core issues facing the country to which the government bears responsibility.

More significantly, Yunus and his administration have had little to say about targeted attacks against known Awami League supporters. According to various reports in Prothom Alo, leaders and members of the Awami League and heads of strategic entities, including the Supreme Court, universities, and the police, have become victims of violence and intimidation. While the military has been spared because of its perceived closeness to the recent uprisings, this uncomfortable alliance could be tested by the moment the interim government fails to present a clear agenda for leading the country towards elections.

The stakes become higher when Islamist groups such as Hefazat-e-Islam and Jamaat-e-Islami seize the advantage to expand their influence. The Dhaka Tribune quoted the Joint Secretary General of Hefazat, Maulana Azizul Haque Islamabadi, as reinforcing the need for unity among Islamist forces. “This unity, or a greater unity, will be of no use if we cannot unite in the battle of the ballots,” he said. The meeting also emphasized a coalition among Islamist groups under Jamaat chief Dr. Shafiqur Rahman, who was praised by other leaders for being pious and leading them towards an “Islamic state.”

The rising profile of Hefazat-e-Islam within the interim cabinet can also be underlined by the fact that one of the most influential Advisers in Yunus’s cabinet is the senior Hefazat leader AFM Khalid Hossain, Adviser for Religious Affairs. This acts to denote the spiraling influence which Islamist figures have in dictating the course of the regime.

The prospect of an Islamist coup is not an abstract fear for reformists and secularists. Taufiq Islam, a youth activist quoted by The Financial Express, came forward with the concern of many thus: “A foothold in politics would mean the implementation of Islamic rules like Sharia law, which is against the very creation and idea of Bangladesh.” Memories of Hefazat-e-Islam’s violence-soaked history, especially its attacks against religious minorities, further fuel this apprehension. The violence following Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit in 2021, including the attack on a train and desecration of Hindu temples, became a grim reminder that Hefazat does not shy away from violence to reach its goals.

Hefazat-e-Islam, since its formation in 2010, has always opposed any reformist move, like the National Women’s Development Policy Bill aimed at granting equal rights to women, or a reduction in the influence of the clergy in politics. Islamist groups spread anti-India propaganda in an environment of suspicion and division. According to recent reports from The Daily Star, members of the interim government have links with activists who have been at the forefront of protest campaigns such as “India out” that have gained momentum since the January elections.

The future of Bangladesh is at a crossroads. As the stormy political waters are being braved by Yunus, the country remains divided between the promise of a secular, democratic future and the resurgence of forces that fight to impose an Islamist state. Over the coming months, the future course of Bangladesh will either preserve the spirit of its founding or suffer a sea change in its national identity.