- The proximity of the river facilitated transportation of heavy materials and labor force required for pyramid construction

- Cutting-edge radar satellite imagery revealed the river’s path buried beneath desert sands

- The river’s entombment likely began during a major drought around 4,200 years ago

A team of researchers has finally announced the exciting discovery of a dead branch of the Nile River in Egypt. It is hoped that this discovery of the dead river branch might help solve that mystery. For centuries, the majestic pyramids of Egypt have captured the world’s imagination, yet the logistical feat of constructing these monumental structures in the arid desert landscape remained an enigma.

You can also read: What Lies Beyond Human Brain Intricate Pathways?

When thinking of the seven wonders of the world, the first that comes to mind is the pyramids of Egypt.

Constructed nearly four and a half thousand years ago, this amazing structure continues to fascinate people with its architecture and the mysteries surrounding its construction.

There are various theories about the pyramids, including that they were built by aliens from another planet or that the pharaohs constructed them for grain storage.

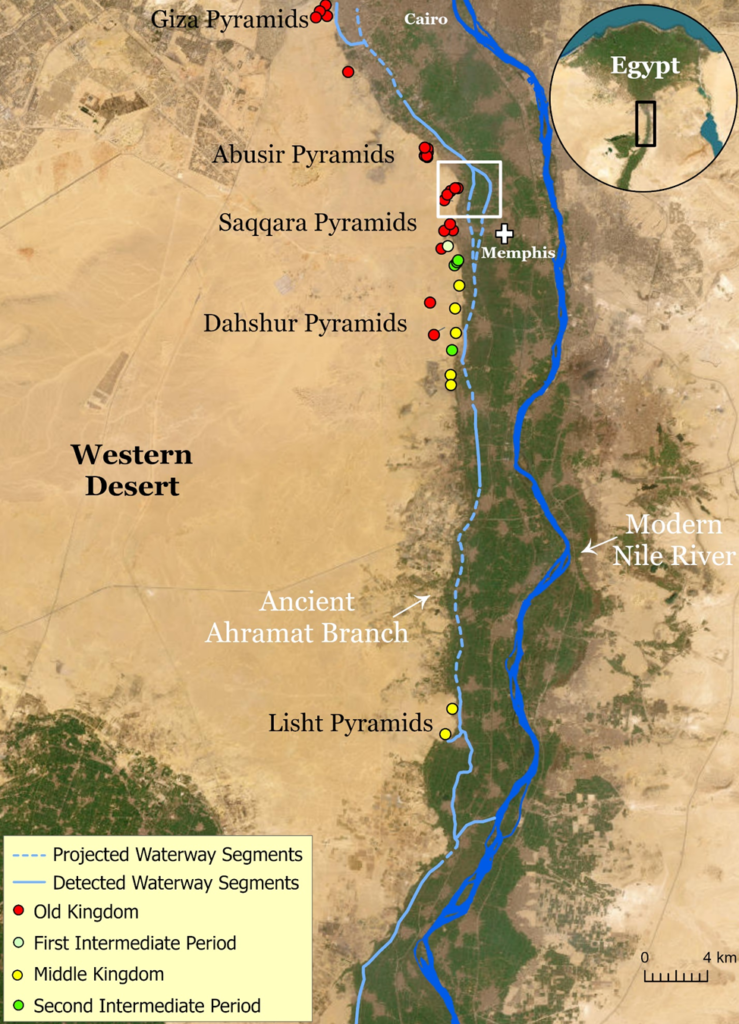

According to a study by the University of North Carolina Wilmington, the recently discovered 64-kilometer-long dead branch of the Nile had been hidden beneath Egypt’s desert and agricultural lands for thousands of years. The research indicates that this river branch flowed alongside 31 pyramids in Egypt. It was through this river that large stone blocks were transported.

It is believed that this recent discovery might reveal the construction secrets of the pyramids built 3,700 to 4,700 years ago.

Beginning of Pyramid Construction

Before the construction of the pyramids, the Egyptians had a different method of burial. At that time, burials took place in small rectangular structures known as ‘mastabas’.

It states that around 2780 BCE, the first pyramid, built in six steps one on top of the other, was constructed in a step-like shape.

Built for a pharaoh named Djoser, this pyramid is considered the first true pyramid, even though its corners were not smooth. It is commonly believed that the designer of this tomb was named Imhotep, who is regarded as the first architect of the pyramids. After the construction of the first pyramid, subsequent pharaohs began to build larger and more refined pyramids.

Three pyramids, three rulers

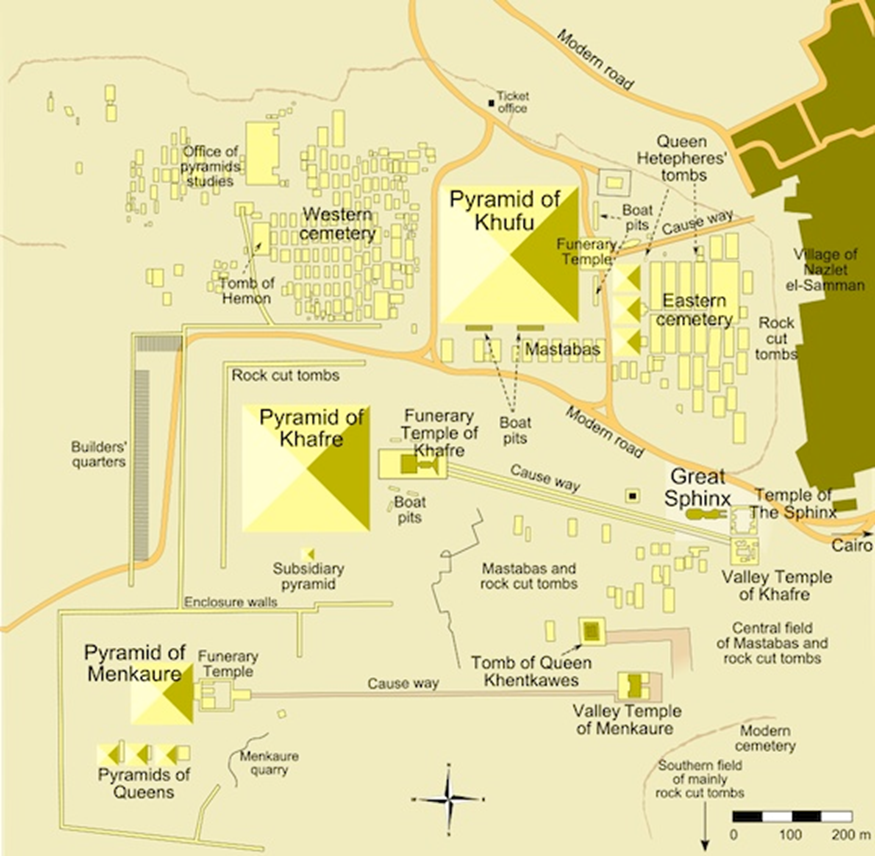

The newly discovered river branch meandered through a region near the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis, where some of the most famous pyramids stand, including the Great Pyramid of Giza – the sole surviving wonder of the ancient world – as well as the Khafre, Cheops, and Mykerinos pyramids. Each pyramid was part of a royal mortuary complex that included a temple at its base and a long stone causeway, some nearly a kilometer in length, leading east from the plateau to a valley temple on the edge of the floodplain.

Archaeologists long suspected that the ancient Egyptians must have utilized a nearby waterway to transport the colossal stone blocks required for pyramid construction.

Yet, as lead study author Eman Ghoneim of the University of North Carolina Wilmington lamented, “nobody was certain of the location, the shape, the size or proximity of this mega waterway to the actual pyramids site.”

Using cutting-edge radar satellite imagery, an international team of researchers mapped the elusive river branch, dubbed “Ahramat” – Arabic for “pyramids.” As Ghoneim explained, “Radar gave us the unique ability to penetrate the sand surface and produce images of hidden features including buried rivers and ancient structures.” Subsequent field surveys and sediment core analyses further corroborated the river’s existence, as detailed in the study published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

According to the scientists, this once mighty river gradually became entombed in sand, potentially starting during a major drought around 4,200 years ago. For millennia, its path alongside the legendary pyramids lay concealed beneath the desert, until this groundbreaking discovery shed light on how these ancient wonders were constructed.

Easier to Float Down the River

The Giza pyramids were situated on a plateau approximately one kilometer away from the riverbanks. According to Ghoneim, many of these pyramids were accompanied by ceremonial raised walkways that ran parallel to the river and terminated at the Valley Temples, serving as harbors.

This suggests that the river played a pivotal role in transporting the massive building materials and labor force required for pyramid construction.

Suzanne Onstine of the University of Memphis, a co-author of the study, highlighted the logistical challenges of constructing such colossal structures.

She noted that the heavy materials, predominantly sourced from the south, would have been far easier to transport by floating them down the river rather than over land.

Additionally, fluctuations in the river’s course and volume over time may have influenced the strategic placement of the pyramids across different dynasties, reflecting the intimate relationship between geography, climate, and human behavior.

This discovery underscores the significance of ongoing research initiatives focused on unraveling the mysteries of the iconic pyramids.

Giza’s Smallest Pyramid

Earlier this year, (2024) an ambitious restoration project was initiated by an Egyptian-Japanese archaeological mission, aiming to restore the smallest of Giza’s renowned pyramids to its original state from over 4,000 years ago. The project involves repositioning hundreds of granite blocks, once part of the outer casing of King Menkaure’s pyramid.

In addition to the major structures, several smaller pyramids for queens are arranged as satellites. A large cemetery of smaller tombs, known as mastabas (Arabic for ‘bench’ due to their flat-roofed, rectangular shape with sloping sides), fills the area to the east and west of Khufu’s pyramid. These mastabas were arranged in a grid-like pattern and constructed for prominent members of the court. Being buried near the pharaoh was a great honor and ensured a prized place in the ‘Afterlife’.

Meanwhile, recent advancements in technology have brought new insights into the mysteries of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Utilizing space-based radiation, a team of archaeologists and scientists uncovered a 30-foot-long corridor hidden within the ancient structure, offering a glimpse into its concealed chambers and corridors.

Construction

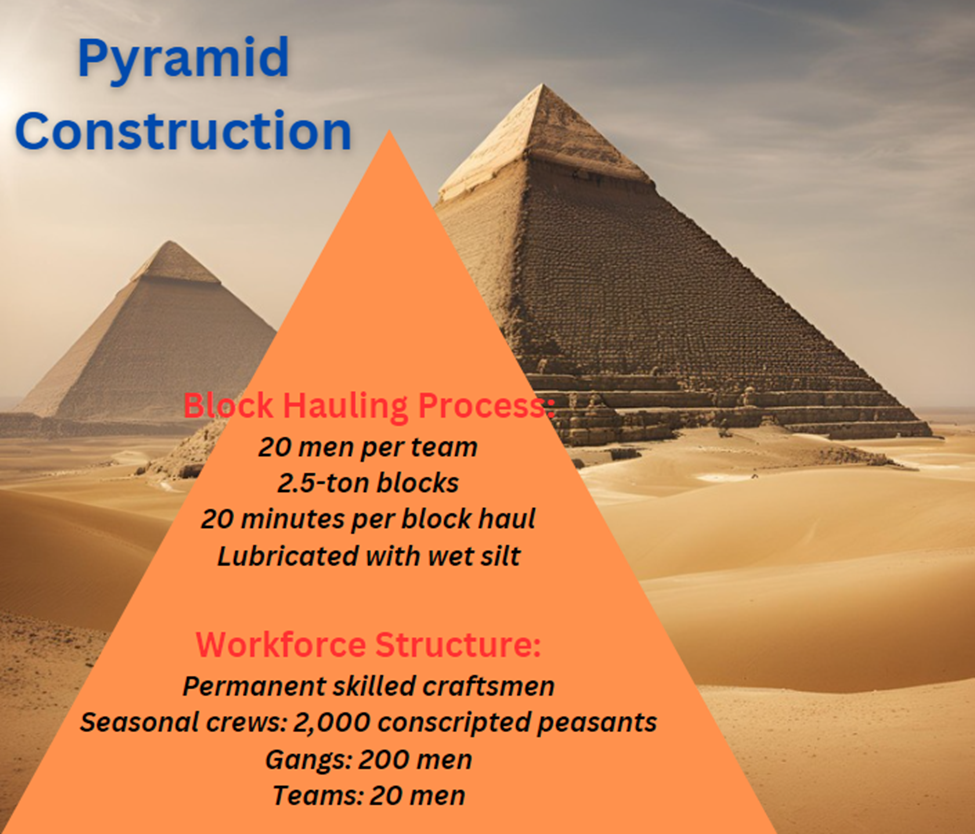

Many questions remain about the construction of these massive monuments, and theories abound. The workforce needed is still debated, but the discovery of a workers’ town south of the plateau provides some answers. A permanent group of skilled craftsmen and builders was likely supplemented by seasonal crews of about 2,000 conscripted peasants. These crews were divided into gangs of 200 men, further split into teams of 20. Experiments show that teams of 20 men could haul 2.5-ton blocks from the quarry to the pyramid in about 20 minutes using a lubricated surface of wet silt. An estimated 340 stones could be moved daily, especially considering that many blocks used in the upper courses were smaller.

World’s oldest wonder

The Great Pyramid of Giza, often hailed as the world’s oldest wonder, has fascinated scholars for centuries, even drawing the attention of the Greek historian Herodotus. As the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it stands as a testament to the ingenuity of its builders, remaining largely intact through the ages. For millennia, from its construction until the completion of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, it held the title of the tallest structure on Earth.

Today, the pyramids continue to stand as Egypt’s most significant historical attractions, drawing visitors from around the globe. While the mystery of how the ancient Egyptians constructed these immense structures with massive stone blocks remains unresolved, ongoing research, such as the measurements conducted by the ScanPyramids team, offers valuable insights into their construction methods and internal architecture.