The struggle for democracy has been a major theme of the year 2022. It was a topic of discussion during the U.S. midterm elections, the first election following former President Donald Trump’s unfounded allegations that the 2016 presidential election was fraudulent. It was also a crucial issue in significant elections in Hungary and Brazil, where incumbents claimed, without evidence, that voting fraud and international meddling would invalidate the outcome. Democracy faces an existential threat around the globe.

According to the V-Dem Institute, a research watchdog based in Sweden, the amount of democracy enjoyed by the typical individual around the world in 2021 declined to levels seen in 1989. This indicates that the democratic advances made over the past three decades have been drastically eroded. In 2021, about one-third of the world’s population lived under authoritarian control, and the number of countries trending toward authoritarianism is three times that of countries leaning toward democracy.

Democracy in decline

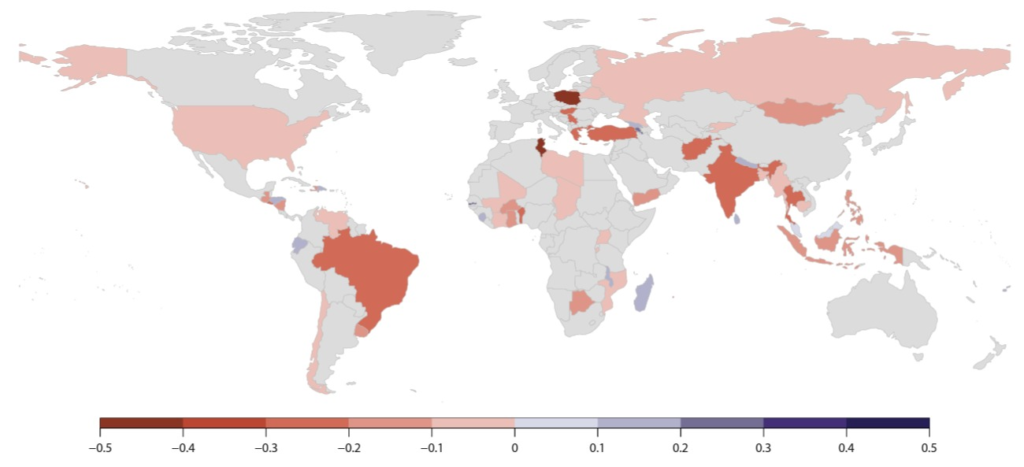

The fall of democracy is most prominent in Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and Asia-Pacific, as well as portions of Latin America and the Caribbean, where the rule of law has been under attack. For example, in some Latin American and Caribbean countries, attacks were made on electoral management bodies, constitutional courts, the media, and national human rights institutions.

COVID-19 was also used as an excuse by some governments to cut back on public oversight.

Loss of trust in institutions has created fertile ground for populist leaders and groups, who seize the chance to blame everything on “democracy and human rights.”

YOU CAN ALSO READ: MYANMAR AND ROHINGYA CRISIS CENTRALITY, CONSENSUS AND CLEAVAGES OF ASEAN WAYS

“Democracy is not working well on a global scale,” asserts former Costa Rican politician and current secretary general of International IDEA Kevin Casas-Zamora. International IDEA has discovered that the number of countries going toward authoritarianism is more than double the number of countries moving toward democracy. 52 of the 104 democracies covered in investigations are deemed to be in decline, an increase from 12 a decade ago. About half of non-democratic nations, such as Afghanistan and Belarus, are growing more autocratic.

The democracy ratio by classifications

According to the Economic Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) most recent Democracy Index (DI) for 2022, only 24 of the 167 countries examined by its model, or 43 percent, can be termed “full democracies.” The approach classifies countries based on the prevailing degree of democratic behavior using four categories: (a) full democracy; (b) flawed democracy; (c) hybrid democracy; and (d) autocracy.

The number of ‘flawed democracies’ in its latest DI is 48, while 59 are autocratic (the same number as in 2021), and 36 are ‘hybrid democracy,’ (an increase from 34 the previous year). While some countries have improved (47), 92 countries’ index scores have either remained unchanged (48) or dropped (44) in last year.

The EIU views it as a bad outcome considering the magnitude of changes to various metrics connected to limits on personal liberty after the pandemic lockdowns and other limits were lifted in 2022.

Full democracy:

In terms of the number of ‘full democracy’ in 2022, the industrialized nations of western Europe led the world in 2022, with 14 of the total 24 ‘full democracies’. The EIU defines “full democracy” as countries that protect civil rights with political freedom and promote democratic values through political culture. Only Canada in North America is a “full democracy.”

Flawed democracy:

Flawed democracies have fundamental civil liberties with occasional infringements, low voter turnout, media partisanship, generally fair and free elections, and losing parties denying electoral results. France, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Hungary, Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka are included in the category of “flawed democracy”.

The US remains a “flawed democracy” after being demoted in 2016.

Hybrid democracy:

Regular electoral frauds prohibiting free and fair elections, limits on political opposition and denial of free speech, non-independent judiciary, pervasive corruption, controlled media, weak rule of law, underdeveloped political culture, low levels of political involvement, and lack of competent governance have all been characterized as hybrid democracy (common in developing countries).

Turkey, Armenia, Ukraine, Mexico, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Pakistan are examples of “hybrid democracies.”

Autocracy: China, Russia, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Belarus, and Azerbaijan comprise the category of “autocracy” (government in which one person possesses unlimited power).

The democratic erosion

The severity of the democracy erosion varies from region to region. According to International IDEA, in the previous five years, approximately half of Europe’s democracies have been eroded. In the Asia-Pacific area, 54% of the population resides in democracies, the vast majority (85%) of which are weak or regressing. The Americas are home to three of the seven countries that are going backwards.

“Democratic erosion affected 12% of democracies a decade ago. That proportion has gone up to 50% now,” asserts Casas-Zamora.

This democratic deterioration coincides with another worrisome trend. The progressively diminishing percentage of people who trust democratic systems to address the most serious challenges of the day, such as rising food and energy prices, soaring inflation, and recession.

According to studies, global satisfaction with the democratic process has declined significantly in recent years. 52% of respondents in 77 nations believed that having a strong leader who is not beholden to legislatures or elections is a positive thing, up from 38% in 2009, according to a report by International IDEA referencing a 2021 World Values Survey research.

Why countries are backsliding? Could it be minimized?

Different organizations use different methods to find backsliding countries. For IDEA, whether or not a country is backsliding depends on a number of factors, such as the effectiveness of its institutions (can the state hold fair and regular elections? ), its checks and balances (is executive power limited? ), and how it protects basic rights (are civil liberties protected?). IDEA also considers other factors, such as impartial administration (is corruption a challenge?) and civic participation (do citizens participate beyond elections?).

Aside from reducing inequality, one of the most important things a country can do to stop its democracy from going backwards is to protect its checks on executive power. These checks include institutions such as the judiciary, a free press, and civil society. For democracies, this entails preserving the integrity of their elections, the most essential check on authority.

Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, states, “Independent, rule of law-abiding institutions play a key role in ensuring the necessary checks and balances. They provide the ultimate foundation for stronger and resilient democracies.”

According to her, to prevent democratic regression, political and financial assistance to foster public engagement, media freedom, and civic education is necessary. Prioritizing investment in these foundations of democracy and supporting them via political action can go a long way toward resolving a number of the problems currently confronting the global community.

“In line with their international human rights obligations, Governments need to protect and promote the space for people to engage in public affairs, to voice their views and concerns freely, safely and without fear, including though peaceful protests and other forms of civic engagement,” Michelle added.

What’s ahead of 2023?

One of the few bright spots in the current state of global democracy is the widespread occurrence of civic action, from worldwide rallies bringing attention to the climate issue to enormous protests in repressive regimes like Iran and China.

Indications from the past suggest that democracy will continue to face serious challenges in the future. “The next few years are going to be extraordinarily challenging for democracy and we’re going to see a lot of people on the street,” says Casas-Zamora.

“This is a double-edged sword, because on the one hand this can create a lot of political instability; on the other hand, it’s also an exercise of democratic rights. It will create a lot of instability but it will also prove the willingness of people to demand their rights, which is not a bad thing,” he added.