Bangladesh’s foreign policy principle of ‘neutrality’ served well as armour during the Cold War and post-Cold War period. It has successfully avoided taking sides in a great power competition and engaging in any security or military alliance system. Hence, IPEF presents a critical dilemma for the Bangladeshi policymakers since, at least on the face of it, the Framework has economic connotations. However, Bangladesh is not taking any quick decision on joining any initiative that might be interpreted as taking sides, as Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen said, IPEF is an understudy subject and national interest will determine Bangladesh’s decision, writes ASM TAREK HASSAN SEMUL

FINDING THE MISSING PIECE

The reemergence of China as a great power and the change in global distribution of power has shaped international politics in the last decade or so. Under Xi’s leadership, China has become the powerhouse of global manufacturing and more assertive in its global ambition and posture. On the other hand, the United States of America (USA) under the Trump administration was turned into a reluctant leader of the “free world”, which started questioning the idea of providing “free public goods”. Washington’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017 under the Trump administration was one of those

ALSO, YOU CAN READ: A NEW WORLD ORDER?

examples, along with the threats to curtail down on the United Nations (UN) and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) funding. These raised doubts among the allies regarding Washington’s commitment towards leading a plethora of multilateral initiatives once built and sustained by the USA itself. The incumbent Biden administration inherited one such initiative called the Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS), which is believed to be created to contain China’s growing influence on the Indo-Pacific and beyond. China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) and Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI) intend to play a supportive role in the plan for infrastructure-led growth and development for several Indo-Pacific countries.

The Foreign Minister of Bangladesh famously described China’s role at the Munich Security Conference of 2022, where he said China has come forward with a “basket of money” along with “aggressive and affordable” proposals.

This put the Western-built Britton Woods organisations in competition with China’s connectivity plans for the Indo-Pacific region. During the Cold War era, these organisations played an instrumental role in a bid to build an alternative global economic regime for the USA, an alternative to the Soviet’s socialist system. In the post-Cold War era, Bretton Woods organisations supported sustaining the neo-liberal order and facilitated the spread of democracy and intensification of the globalisation process. China exploited this “neo-liberal order” well in the 1990s to integrate itself with the global production network as well as ensure its “peaceful rise”. For two reasons, financial loans provided by the Bretton Woods organisations started to face stiff competition with the introduction of BRI in 2013.

Asian economic resurgence can be partly attributed to the rise of the Southeast Asian economies and China’s unprecedented economic growth in the last two decades. Following the same development path, many other regions in Asia tried to fashion their economic growth based on manufacturing and exportoriented sectors. However, such a detour from agronomic society to industrialisation requires massive overhauling of the energy and infrastructural sectors. Often such overhauling led to high expectations that mega-infrastructure building projects will bring infrastructure-driven growth for countries due to increased investment and employment. Whereas the World Bank and IMF loans are apparently known to be attached with conditionalities or “strings”, BRI provided the much-soughtafter finances. Therefore, when IPS was introduced as the grand strategy to contain China’s growing dominance over the IndoPacific region, the economic or financial piece was missing that could successfully counterbalance BRI.

FILLING THE VOID

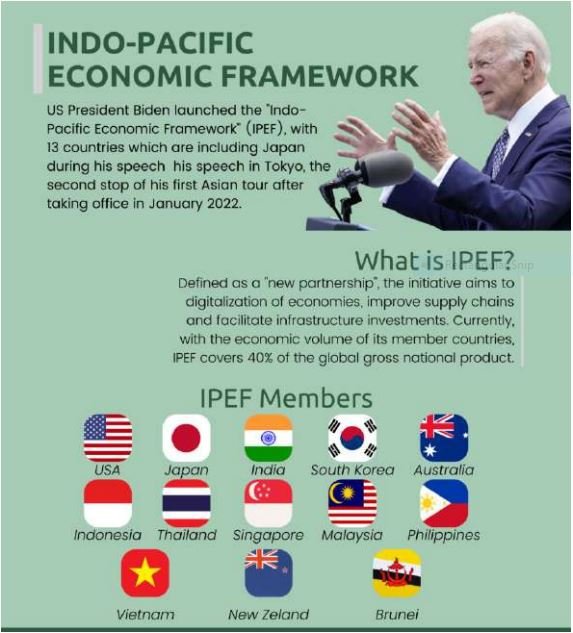

Following the USA withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) under the Trump Administration, countries which are parties to the Agreement continued anyway without Washington and built the new Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TransPacific Partnership (CPTPP). CPTPP represents around 13% of the world’s GDP and, on a global scale, is one of the largest free-trade zone, which is in the process of taking China and the UK on board. Hence, it was imperative for President Joe Biden to introduce the missing economic piece to clarify USA’s foreign policy direction and engage with the Indo-Pacific region. On 23rd May 2022, Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) was unveiled in Tokyo during Biden’s first visit to Asia since taking office. Initially 13 countries and later with Fiji joining the IPEF made it an organisation comprising of 14 member countries, which roughly make 40 per cent of the world’s GDP. The USA, Japan, India and South Korea are among the largest economies in the world that are members of this formidable economic bloc.

ministerial pillar meeting at the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework’s

Ministerial in Los Angeles on September 8.

The geographical configuration of the member states of the IPEF gives the impression of being distinctly Indo-Pacific, where Southeast Asian countries connect major economies from both the Indian and Pacific oceans. Barring the usual suspects like Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia, all the ASEAN countries featured in this initiative. Such overwhelming participation from the ASEAN counties should not be taken as a major foreign policy shift but rather as evidence that Southeast Asian nations are hedging between the USA and China. One of the significant drawbacks that can disappoint the existing and aspiring members is that the IPEF is not a free trade agreement (FTA). The Trump administration’s anti-FTA received significant popularity in the public domain and became a populist agenda to substantiate the “America First” narrative.

Therefore, it was assumable that the Biden administration would not risk the economic centrepiece of their IPS by opening up the USA market for Asian countries. Washington needed an economic framework that would set some binding rules for trade and economic engagement and shape a “rule-based order” to make China’s engagement difficult if it does not follow suit. Unlike Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) and CPTPP, the IPEF does not intend to advance reciprocal tariff-free access for member countries. Rather, it has identified four pillars to work on:

(i) fair and resilient trade (encompassing seven subtopics, including labour, environmental, and digital standards); (ii) supply chain resilience; (iii) infrastructure, clean energy, and decarbonisation; and (iv) tax and anti-corruption.

The USA intends to get back its “rule-shaper” status by creating a favourable environment for itself that would influence trade and investment, such as supply chain resilience, digital economy, cross-border data standards, decarbonisation and energy efficiency. However, with China being the largest trading partner with most of the IPEF members, it will be difficult to decouple China from the supply chain network in the Indo-Pacific. What’s more, China is the second-largest economy and the largest global manufacturer, establishing USA’s dominance on trade and investment rules in the Indo-Pacific region might be a long shot. Therefore, instead of Trump’s “trade war”, the “precise decoupling” of China is a difficult but much more lucrative proposition for Washington to achieve.

Washington understands the dilemma of prospective countries in joining such an initiative, which might antagonise China and leave little space for manoeuvring. Consequently, IPEF sets a low threshold for joining and allows member states to choose between different issues and modules and leave out pillars that they are not comfortable with. Lack of a clear roadmap, fluidity in nature, non-inclusion of tariff reduction and market access might be the drawbacks of this initiative. Potential members find the incentives a little as opposed to when it comes to getting engaged in a great power competition in the Indo-Pacific region as a price. On the other hand, Washington is trying to take partner countries and allies on board by lessening USA’s dependence on China in supply chain networks – especially in the high-tech industry. Since the USA legislature has not approved IPEF, its legal status and future might create doubts among the member states. Maintaining “high-standard” compliance with the issues such as labour and environmental standards, reducing carbon emissions, anti-corruption, and clean energy undermines the political, economic and developmental nuances, complexities and diversities among the member countries. Adhering to the four pillars of IPEF would imply that member states have to change their respective laws, standards and governance system following the “high-standard” set by the USA. On the other hand, removing ambiguity and building a clear and meaningful direction for the Framework will require the Biden administration to convince the Congress and domestic polity. Washington has to be weary regarding giving any concession to the other member states of IPEF when it comes to amassing bipartisan support.

BUILDING BANGLADESH’S POSITION

Despite the intensified competition between the USA and China over the last decade, Bangladesh has maintained a balanced approach towards these two great powers. On the one hand, the USA and its transatlantic European allies have been the biggest export destination for the readymade garments (RMG) industry, at the same time, China has been a significant source of raw materials, infrastructure cooperation, defence purchase etc. Therefore, when Bangladesh was approached to consider joining the Indo-Pacific platform, it brought out the development and economic priorities to the forefront as the apex national interest.

The Foreign Minister of Bangladesh said, “We’re sure that we’ll be effectively engaged in any future ‘Indo-Pacific Alliance’ if it is found to be purely economic in nature.”

Bangladesh’s foreign policy principle of ‘neutrality’ served well as armour during the Cold War and postCold War period. It has successfully avoided taking sides in a great power competition and engaging in any security or military alliance system. Hence, IPEF presents a critical dilemma for the Bangladeshi policymakers since, at least on the face of it, the Framework has economic connotations. However, the way Beijing perceives IPEF signals that IPEF will be securitised by China as it was dubbed as “economic NATO”. Beijing is likely to discuss and negotiate with other Asia-Pacific countries regarding its new initiative Global Security Initiative (GSI), which is thought to be an initiative to counterbalance QUAD.

However, it is clear that Bangladesh is not taking any quick decision to join any initiative that might be interpreted as taking sides, as Foreign Minister AK Abdul Momen said, IPEF is an understudy subject and national interest will determine Bangladesh’s decision. Although the issue of clean energy and decarbonisation might have a polarising impact on IPEF members, many members have developed environment, corporate accountability and labour standards over the last decade or so. Hence, harmonising standards by IPEF states might be on the horizon. In such cases, developing countries like Bangladesh, which are trying to attract FDI or sign FTAs, will face difficulties complying with strengthened business regulations and attaining their national economic interest. Moreover, like many resident countries of the Indo-Pacific, China is critical to Bangladesh’s supply chain network for the RMG industry.

Any sanctions or toughening up of standards might negatively impact the supply chain that the Covid-19 pandemic has already disrupted. Should that happen, Bangladesh, along with many other countries in the Indo-Pacific region that depend on China for raw materials and regard USA and Europe as export destinations will be in trouble. Moreover, with the majority of ASEAN nations joining the IPEF, space for manoeuvring through the troubled water of great power tussle is getting limited. As the number of neutral states shrinks in the Indo-Pacific region, small states like Bangladesh, which wants to stay away from the geopolitical tussle and has so far done well with their hedging between major powers, might have to reevaluate their approach. This compulsion might not go well for a ‘peaceful, inclusive and prosperous Indo-Pacific.’