As Sri Lankan lawmakers, defying Ranil Wickremesinghe’s sizeable unpopularity with the public, elected him as the country’s new President on July 20, the new President told the Parliament that the nation was “in a very difficult situation” and that there were “big challenges ahead.” After sweeping the vote with the backing of the former President Rajapaksa’s ruling party, he called for unity and bipartisanship moving forward. Meanwhile, the island nation remains wracked with protests as the country stands effectively bankrupt and facing acute shortages of food, fuel and other basic supplies.

CIVIL CONFLICT IN SRI LANKA

Political unrest and civil war is quite common in Sri Lanka. Civil conflict raged for decades between the Sinhala-dominated government and the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) – killing 100,000 people. The conflict concluded in 2009 with a government triumph. Situation was calm until the 2019 Easter Sunday suicide bombings, which killed more than 200 people and were blamed on a little-known Islamic group. Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a former military commander regarded by many people as a civil war hero, was elected President months later. But due to policy failures, Sri Lanka being Asia’s oldest democracy since 1931 is struggling both politically and economically.

WHAT’S PULLING SRI LANKA TO PIT?

The impact of coronavirus pandemic prompted Sri Lanka’s financial problems, which were compounded by Rajapaksa’s government’s incompetence. Sri Lanka had $7.6 billion (£5.8 billion) in foreign currency reserves at the end of 2019, which have since fallen to roughly $250 million (£210 million). The country currently procures $3 billion (£2.3 billion) more than it exports each year, which puts continued pressure on its foreign currency.

Rajapaksa, in his tenure, was faced with criticism for the large tax cuts he implemented in 2019, as Rajapaksa declined to take loan from IMF then, which cost the government more than $1.4 Billion (£1.13 Billion) every year.

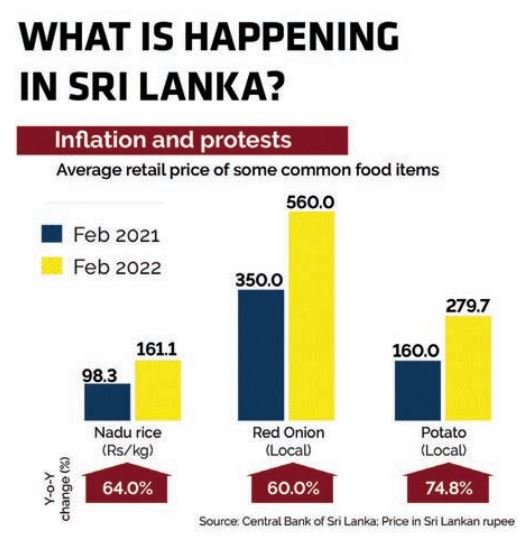

Late last year, the country was unable to fund even the most fundamental imports, and it has since defaulted on its obligations. Dissatisfaction has been building for months due to acute food and fuel shortages, record inflation and extended power outages.

Even Rajapaksa’s closest supporters began to reject him, and when demonstrators stormed his official house in Colombo July 10, 2022, he was forced to flee to a navy base in fear of his life. Borderless corruption, nepotism, imbalanced judiciary, scattered law & order situation, arbitrariness in ruling of Rajapaksa government- forced Sri Lanka to accept this fate. Rajapaksa resigned publicly on July 14, after 32 months into his five-year mandate. Gotobaya Rajapaksa fled to Maldives before reaching Singapore in a military jet.

It is also described that a string of devastating bomb strikes in 2019 scared off tourists, which adversely impacted Lankan economy as tourists are considered as a vital sector in the economy. Sri Lanka’s defective financial policy affected them previously. Unplanned debt receiving, corruption in taking loans, especially from China, cost the country to sacrifice Hambantota port, the principle port of Sri Lanka. Currently, due to foreign currency shortage, Sri Lanka is unable to pay debts while the interests increasing. The vicious circle of debt has twisted Sri Lanka.

Keeping aside financial collapse, Rajapaksa government established worst example of nepotism by making Mahinda as Prime Minister, his brother Gotabaya as President, son Namal as Minister of the sports and youth affairs, other son Yoshitha was elevated to the powerful post of the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, other brother Basil as Finance Minister and another brother Chamal as Minister of Irrigation and Chamal’s son Shasheendra was accommodated as Minister of Agriculture. Moreover, Mahinda’s brother-in-law, Nishantha Wickramasinghe, was appointed Head of Sri Lankan Airlines.

Ongoing anti-government protestors in Sri Lanka, since last four months, have lamented rising prices of basic commodities and an economic crisis that has nearly depleted the country’s foreign reserves, dried up remittances and fuelled inflation. Although the protests have been furious, they have mainly been nonviolent but still badly impacted the economy. Many think the root of Sri Lanka’s downward graph lies in the continuous political unrest.

FOREIGN INFLUENCE AND DEBT PRESSURE

To help stabilise the economy, the Sri Lankan government has approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a quick funding and a bridging loan. In order to get an IMF loan, Sri Lanka would need to adopt a debt restructuring plan. The rejection of debt restructuring by China is concerning as Sri Lanka owes Beijing $6.5 billion. Statistics say that the debt of Sri Lanka to China is 08% of the entire national income of Sri Lanka – making them the biggest borrower from China. Falling in China’s ‘debt trap’ under the Belt and Road Initiative, Sri Lanka surrendered control over Hambantota port in 2017. Lured by China, Sri Lanka adopted mega projects and construction of luxurious infrastructures like Colombo Port City, stabbed their overall economy, making them bait for cementing China’s influence in the region. What the government considered as the ‘white gold’ for economy ended being the ‘white elephant’. Sri Lanka would lose a lot of time if its debt restructuring relied on Paris Club funding (an IMF program) and Chinese involvement if China slowed the process. Former Cabinet spokesperson Nalaka Godahewa confirmed the Chinese reservation, saying the government’s sole concern is China’s stance. Geographical position, international corridor and China biased foreign policy trapped Sri Lanka be a battlefield for influence establishment between China and India. India, however, approached Sri Lanka with $3.5 billion aid in emergency, whereas, Sri Lanka requires a minimum of a billion per month to normalise import process of basic commodities.

The $81 billion economy of Sri Lanka is on the verge of collapse as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raises global prices for oil and other commodities. Due to a foreign currency shortfall, Sri Lanka stated in April that it would halt repayment of international debts. The government has hiked interest rates, depreciated the local currency, and imposed import restrictions on non-essential items. Sri Lanka’s development is slowing, and inflation is hitting high, consumer prices increased over 30% year on year in April, following a 19% increase in March. However, with only $2 billion in foreign exchange reserves and $7 billion in debt payments due this year, restoring the country’s economic health would be difficult. Sri Lanka’s combined foreign debt is $51 billion, of which $28 billion must be repaid by the end of 2027. Sri Lanka’s economy and fate of 21.92 million people is swinging like pendulum; irony is they don’t have control of the pendulum.

A NEW PRESIDENT OPPOSED BY MANY

Facing the task of leading the country out of its economic collapse and restoring order after months of mass protests, Wickremesinghe in presidential race roundly defeated his main rival for the job, Dullus Alahapperuma, with 134 votes to 82 in a parliamentary vote. A former six-time prime minister, he failed in his previous two runs for the presidency. But his victory on July 20 means he will serve out the rest of the presidential term until November 2024. Viewed by many as a shrewd political operator, Wickremesinghe managed to cling on in the Parliament despite his party being wiped out in the 2020 election. It failed to win a single constituency, and its only seat – for which Wickremesinghe nominated himself – was awarded under the party list system reflecting overall votes polled.

As Gotabaya Rajapaksa formally resigned as the President of Sri Lanka, putting an end to the days of ambiguity that had followed the ousted leader’s flight from the island amid fierce public outcry over the nation’s economic problems, the Speaker of the Parliament Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana addressed the media on July 15 saying, “I have accepted the resignation,” which was televised on the national channel of the island nation. The protesters had also called for resignation of Wickremesinghe, a close ally of the Rajapaksa political family who was appointed Prime Minister in May. Protesters earlier burnt down his private home and also stormed his prime ministerial office in Colombo in demonstrations against his leadership. But on July 20, he managed to surprise many with many others being dismayed and disappointed over his win.

IS INDIA GAINING OVER CHINA IN SRI LANKA?

During the recent anti-government protests, Sri Lankan protesters while shouting slogans targeting former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his family also raised chants against India. A number of their slogans hurling abusive languages could be widely heard during the demonstrations. While anti-Indian sentiments like these still persist, how Sri Lankans view India might be changing as the country grapples with political and economic chaos. The island nation is in the midst of unprecedented economic crisis that has sparked massive protests, and forced its President to quit after fleeing the country. Sri Lanka over the years has built up a huge amount of debt – to the point that it is now struggling to buy essentials such as food, fuel and medicine. Some sections of the Sri Lankan politics have always viewed with suspicion the presence of its bigger and powerful neighbour, India. Over the years, majority Sinhala nationalists and leftwing parties led several anti-India protests in Sri Lanka. But Sri Lanka turned to India as it suddenly found itself in a deep economic mess months back and the BJPled government in Delhi responded with financial help, which was not the first time though. In fact, no other country or institution has helped Sri Lanka as much as India did in the past year. Analysts are of the view that Sri Lanka’s desperate financial need, in a way, has helped Delhi regain its influence on the island nation of 22 million people after China made inroads by offering loans and other forms of financial aid for infrastructure or mega projects in the past one and a half decades.

CAN WICKREMESINGHE BRING MUCH-NEEDED UNITY?

New President Ranil Wickremesinghe faces the immediate task of trying to lead Sri Lanka out of economic collapse and restore public order. He has been promoted from being Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister to its new President within a matter of days. He now has the job he has long coveted – but the challenges he faces are monumental. “Our divisions are now over,” he told Parliament in a short acceptance speech upon getting elected by his fellow MPs, and urged his opponents to work with him for the greater good of the country. However, many doubt whether Sri Lanka can unite under Wickremesinghe and his opponents question his mandate to serve out the current term before elections in late 2024, even though constitutional procedure has been followed. He is the sole MP of the party that he leads and he owes his election to top office to the members of the ruling SLPP party, led by the Rajapaksas. The new president’s deep unpopularity could trigger more unrest at a time when Sri Lanka needs political stability so it can resume stalled negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout package. He has been prime minister six times, but has never seen out a full term. His latest prime ministerial stint began as recently as May, when he was named to the post in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt by Mr Rajapaksa to cling to office.

For months now, people have been struggling with daily power cuts and shortages of basics such as fuel, food and medicines. The country’s foreign currency reserves have virtually run dry, meaning it doesn’t have enough funds available to buy goods from other countries. Resentment at these growing hardships boiled over, forcing Gotabaya Rajapaksa out of office – and Mr Wickremesinghe will be aware the same fate could await him. In the last election, his UNP was almost wiped out, managing to scrape together just one parliamentary seat, leaving him its sole representative in parliament – and fuelling his opponents’ claims that he lacks legitimacy for office. One major reason people are angry at Mr Wickremesinghe has been his perceived closeness to the Rajapaksa family. Many people believe he helped shield them when they lost power in 2015. In an effort to shore up his authority when he was named acting president, Mr Wickremesinghe instructed a new committee headed by the military and police chiefs to “do what is necessary” to restore order. There are fears he could order security forces to come down hard on protesters if they demonstrate against him, particularly as the financial pain shows no sign of easing soon. The economic crisis was “going to get worse before it gets better”, he told the BBC in May. But the turmoil is now so great that it is unclear what measures will be equal to the task – or whether Mr Wickremesinghe is the man to do it.

HOPES FADED?

People in the island are suffering because of Sri Lanka’s struggle to pay for crucial imports like food, fuel and medicine for its 22 million people as it battles a foreign exchange crisis. Inflation has soared about 50%, with food prices 80% higher than a year ago. The Sri Lankan rupee has slumped in value against the US dollar and other major global currencies this year. In Sri Lanka, many blamed Rajapaksas for mishandling the economy with disastrous policies whose impact was only exacerbated by the pandemic. The entire country came to a standstill where no hope remained visible. Bad governance, biased foreign policy, internal conflict and corruption, extended nepotism and overall arbitrariness in leadership bankrupted Sri Lanka while facilitating opportunists and keeping the commoners mired in sheer hopelessness.