The release of 23 Palestinian child prisoners as part of a recent ceasefire agreement has renewed scrutiny of Israel’s detention and prosecution of Palestinian minors. These children were among the 290 Palestinian prisoners freed following the January 19 ceasefire that ended 15 months of relentless Israeli bombardment in Gaza. According to the Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, before the latest prisoner exchanges, at least 320 Palestinian children were being held in Israeli prisons.

But why are Palestinian children imprisoned in such significant numbers, and under what legal system are they prosecuted? The answers lie in a dual legal structure that disproportionately affects Palestinians and subjects them to a military court system that international rights groups have long criticized.

The realities of Palestinian child prisoners

In 2016, Israel enacted a controversial law allowing children as young as 12 to be held criminally responsible for certain offenses, including murder, attempted murder, and manslaughter. Although prison sentences can only begin after a child turns 14, the law marked a significant shift. Previously, children under 14 were not subject to imprisonment.

The law came in response to the arrest of Ahmed Manasra in 2015. Manasra, 13 at the time, was accused of attempted murder in occupied East Jerusalem. After the law was enacted, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison, a sentence later reduced to nine on appeal. His case became a symbol of the harsh measures imposed on Palestinian children within Israel’s legal framework.

Over the past two decades, an estimated 10,000 Palestinian children have been detained under Israeli military law, according to Save the Children. Arrests are often linked to activities as minor as throwing stones or participating in small unauthorized gatherings—actions that are often deemed political by Israeli authorities. These children are interrogated, detained, and prosecuted in military courts, which have been criticized for lacking due process and disproportionately harsh treatment compared to Israel’s civil courts.

A dual legal system

Israel enforces two parallel legal systems in the territories it occupies. While Israeli settlers in the West Bank and East Jerusalem are subject to Israeli civil law, Palestinians in these areas are governed by military law. This disparity creates vastly different experiences for children living in the same region.

Palestinian children accused of offenses are tried in military courts run by Israeli soldiers and officers, while Israeli children, even in the same geographical area, are tried under a civilian legal system. According to the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, nearly 75% of Palestinian children detained in the occupied West Bank remain in custody until the end of legal proceedings, compared to less than 20% of Israeli minors.

The treatment of Palestinian minors during detention has drawn criticism from human rights groups. Children are often arrested during nighttime raids, interrogated without a guardian or legal counsel, and held in pretrial detention for extended periods. HaMoked, an Israeli NGO, reported that during 2020, Palestinian minors in detention were allowed just one 10-minute phone call to their families every two weeks.

Prisoner releases under the ceasefire

The recent prisoner releases, part of a ceasefire agreement between Hamas and Israel, have provided temporary relief for families. Two children were among the 290 Palestinian prisoners released in two waves since January 19. In the first exchange, 90 prisoners were freed, including 21 children.

While these releases are welcomed, they represent a fraction of the overall detainee population. As of Sunday, Addameer estimated that approximately 10,400 Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank remain in Israeli custody. Many of these individuals have been detained for years, some without formal charges or trials.

Among those released was Muhammad al-Tous, a 69-year-old man who had been imprisoned for 39 years after his arrest in 1985. His release highlights the extended duration of sentences served by many Palestinian prisoners. Prominent figures, such as Marwan Barghouti, a co-founder of the Fatah political party, have also spent decades in Israeli prisons; Barghouti has been detained for 22 years.

Abuse and indefinite detention

Palestinian prisoners, including children, often face harsh conditions during detention. Former detainees have reported instances of beatings, torture, and humiliation, both during interrogation and imprisonment. This treatment has only intensified since the start of Israel’s war on Gaza following the Hamas-led attacks on October 7, 2023.

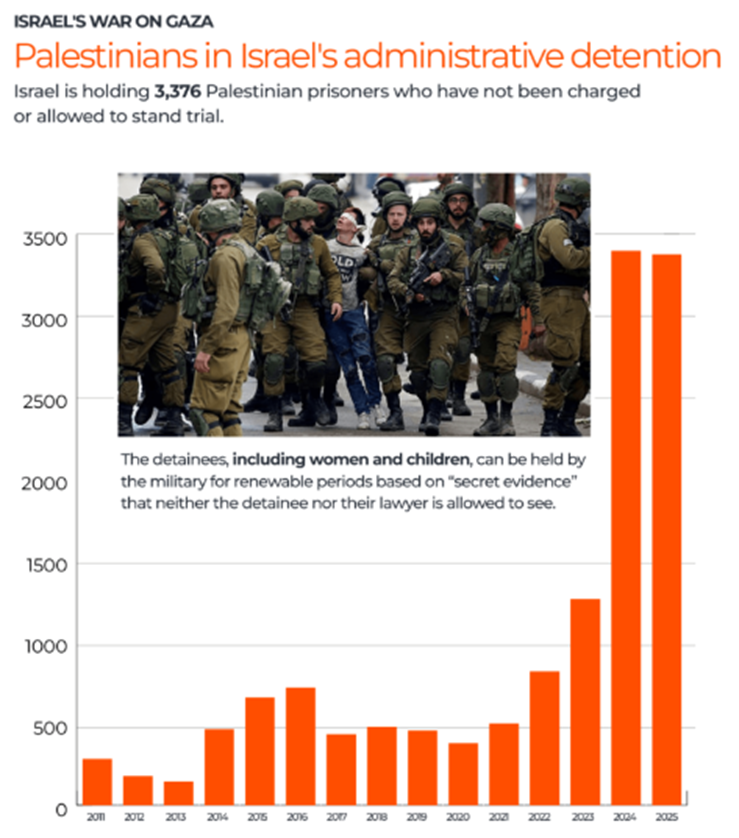

A particularly controversial aspect of Israel’s detention practices is the use of administrative detention. As of January, around 3,376 Palestinians, including 41 children and 12 women, are being held under administrative detention—a policy that allows individuals to be imprisoned without charge or trial. Detainees and their lawyers are denied access to the evidence against them, and their detention can be renewed indefinitely, often lasting for years. This practice has been in place since the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948.

A glimpse of hope or a grim reminder?

The recent prisoner exchanges have offered a glimmer of hope for families of detainees, but they also underscore the enduring inequalities of the occupation. As part of the ceasefire agreement, an additional 26 captives are expected to be released in the coming weeks, along with hundreds more Palestinian prisoners. However, these exchanges do not address the systemic issues that lead to the detention of thousands of Palestinians each year.

For the nearly 2.3 million residents of Gaza, most of whom have been displaced during the ongoing conflict, the ceasefire brings only temporary respite. Talks aimed at resolving the broader conflict are scheduled to begin on February 3, but the path to lasting peace remains uncertain.

As Tamer Qarmout, an associate professor at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, remarked, “These prisoners should have been released through a bigger deal that ends the conflict, that brings peace through negotiations, through ending occupation. But the harsh reality in Palestine is that as we talk, occupation continues.”

What lies ahead?

The release of Palestinian prisoners as part of the ceasefire deal is a reminder of the broader struggle faced by Palestinians under occupation. For the families of detained children, the release of even a few brings immense relief. Yet, the harsh realities of occupation, coupled with systemic inequalities in Israel’s legal framework, ensure that thousands of others remain behind bars.

The next phase of prisoner exchanges offers hope for families still awaiting the release of their loved ones. However, without addressing the underlying issues of military law, administrative detention, and the treatment of Palestinian children, such exchanges will remain symbolic rather than transformative. For now, the plight of Palestinian child prisoners continues to highlight the deep divisions and injustices of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.