A high-stakes global summit aimed at halting nature’s decline concluded in disarray on Saturday, with only partial agreements and major unresolved issues overshadowing the event. COP16, held in Cali, Colombia, saw nearly 200 countries come together for the first time since the landmark 2022 deal aimed at preserving biodiversity. This two-week gathering sought to address crucial goals, such as protecting 30% of Earth’s land and sea, while also tackling environmental harm within the financial sector.

However, negotiations stalled after nearly 12 hours of intense discussions that stretched past the scheduled Friday deadline, ending abruptly on Saturday morning. With several key delegates leaving to catch flights, quorum was lost, and talks were suspended, leaving core issues like funding for nature conservation and monitoring mechanisms unresolved. Delegates will reconvene in Bangkok next year in hopes of finalizing a path forward.

Discontent Among Delegates Over Process and Delays

The drawn-out process provoked frustration among various delegations, who criticized the structure of discussions that left critical topics unresolved until the final moments. “We question the legitimacy of delaying vital issues to the end of COP,” said Brazilian negotiator Maria Angelica Ikeda, just before discussions on funding were cut off. Michelle Baleikanacea, representing Fiji, echoed similar concerns, highlighting that limited budgets left many developing nations unable to extend their stays to continue negotiations. “We are the only Pacific island delegation left here,” Baleikanacea noted, underscoring the financial strain on smaller countries.

Key Breakthroughs Amid the Deadlock

Despite the challenges, COP16 delivered a few significant breakthroughs. Countries agreed on a global levy on products developed using genetic information from nature, a measure expected to raise substantial funds for biodiversity efforts.

This levy, known as the Digital Sequence Information (DSI) fund, could bring in over $1 billion annually, with at least half directed to Indigenous communities and developing nations. Indigenous communities also achieved a milestone, as they were granted a formal, permanent role in the UN biodiversity decision-making process — a historic step hailed as a “watershed moment” for Indigenous representation.

While the DSI fund was approved, uncertainties remained over its formalization due to the reduced presence of countries during the vote, potentially questioning the decision’s validity in the future.

Lack of Financial and Monitoring Strategies Raises Alarms

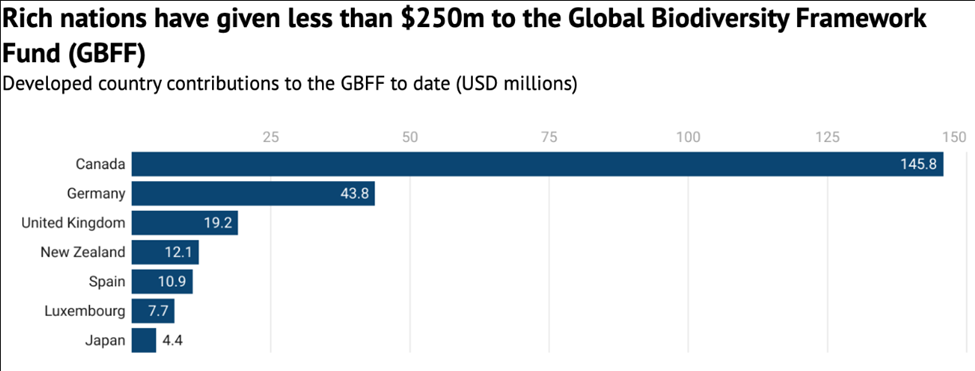

Observers noted that despite these partial successes, the summit’s inability to finalize a strategy for financing conservation efforts leaves a critical gap. The world needs an estimated $700 billion annually to halt biodiversity loss, yet COP16 failed to agree on how to raise the $200 billion per year target set for 2030. Delegates from the Global South voiced concerns that wealthy nations may not deliver on their pledge of $20 billion by 2025, leaving developing countries without crucial resources to protect biodiversity.

“This COP neither secured the promised funding nor instilled confidence that leaders will act urgently,” remarked Sierra Leone’s Environment Minister Jiwoh Abdulai. Critics pointed out that while resources are often rapidly mobilized for crises such as pandemics or wars, similar urgency is lacking for biodiversity — a crisis affecting global ecosystems and economies.

Furthermore, no consensus was reached on a framework for monitoring the progress of biodiversity targets set two years ago in Montreal. The failure to establish monitoring protocols risks repeating past failures, where vague goals led to inadequate action on nature preservation. Despite general agreement on a draft framework, delegates were unable to approve it, having spent excessive time debating more contentious topics.

Conclusion

COP16’s disappointing conclusion has sparked concerns about the global commitment to safeguarding biodiversity. Experts warn that the delays and lack of robust financial and monitoring strategies threaten the decade-long goals to protect ecosystems and reverse environmental degradation. Brian O’Donnell, director of the Campaign for Nature, stressed that “the world doesn’t have time for business as usual,” and urged countries to act with the urgency the crisis demands.