The staggering volume of stressed assets in Bangladesh’s banking sector has plunged the nation into a state of grave concern. Over the past decade, the total volume of Non-Performing Loans (NPL) has increased more than tenfold, swelling from Tk427.25 billion in Q4 of FY12 to Tk1.46 trillion in Q2 of FY24. Yet, this figure merely scratches the surface. Experts suggest that including loans in special mention accounts, court injunctions, and rescheduled loans would elevate the total to a staggering Tk5.50 trillion.

You Can Also Read: MICROFINANCE LEADS BANGLADESH’S FIGHT AGAINST POVERTY

This alarming revelation was presented by the Center for Policy Dialogue (CPD) on Thursday, May 23, 2024, shaking the foundations of Bangladesh’s economy. Dr. Fahmida Khatun, the Executive Director of CPD, disclosed these findings in a keynote paper titled “What Lies Ahead for the Banking Sector in Bangladesh?”

Dr. Khatun also highlighted the troubling transformation of the banking sector into a tool for financial oligarchy under crony capitalism, painting a stark picture of monopolies concentrating financial power and exploiting the masses for their gain.

The Burden of Non-Performing Loans

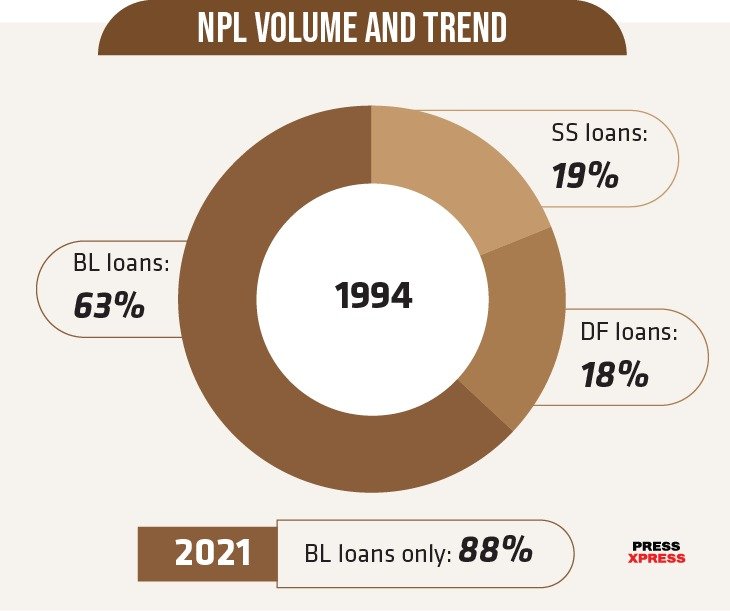

In financial management, loans are classified as unclassified or classified, determining the stability of the banking system. When promptly repaid, they’re termed unclassified; when repayment falters, they become non-performing loans (NPLs). These NPLs, like malevolent specters, haunt the corridors of financial institutions, marked with labels of sub-standard (SS), doubtful (DF), or the most ominous of all, bad/loss (BL), depending on the duration of their delinquency.

Managing NPLs in Bangladesh is daunting, given the vital role of the banking system in the economy. A sustainable banking system requires NPL rates of 2-3%, yet Bangladesh faces disproportionately high rates. The trajectory of Non-Performing Loans rates reflects economic turbulence, from 25% in 1991 to nearly 35% in 2000. Despite some decline, such as 8.06% in 2020, rates surged back to 9% by 2022.

Behind these stark figures lies a tale of culpability, primarily borne by state-owned commercial banks (SCBs) and specialized banks (SBs). In the labyrinth of financial distress, they bear the brunt, with Non-Performing Loans rates soaring to staggering heights. Against the backdrop of a nine percent NPL rate in 2022, SCBs and SBs grapple with rates of approximately 22% and 12%, respectively, painting a dire picture of financial tumult.

In 2022, NPLs reached Tk120,649 crore, a grave threat to economic stability per Bangladesh Bank. Beyond the stark figures lies a narrative of decay, as NPL quality worsens yearly.

The journey from 1994 to now reveals a troubling trend. While SS and DF loans decreased, BL loans surged. In 1994, SS and DF loans were 19% and 18%, with BL loans at 63%. By 2021, BL loans skyrocketed to 88% of classified loans.

Rising Tide of Written-off Loans

In the realm of banking, loan write-off looms ominously—a practice concealing loans deemed irrecoverable. In Bangladesh, loans classified as bad/loss for three years meet this fate. Yet, as banks bid farewell to these non-performing relics, the chance of recouping losses dims to a mere whisper.

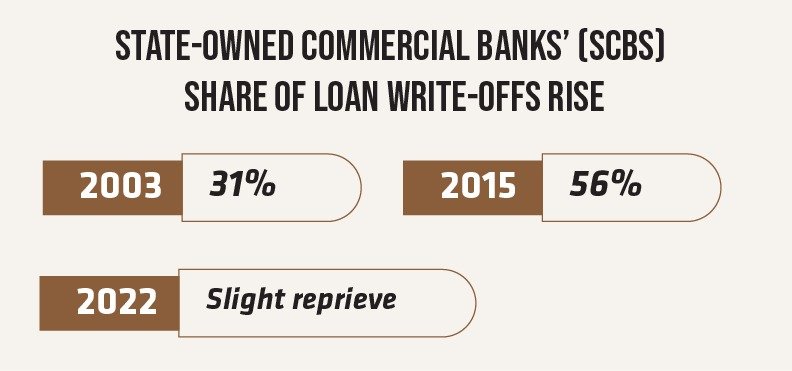

The tale of loan write-offs unfolds like a grim saga, tracing a trajectory of ominous escalation over the years. From a modest Tk3,700 crore in 2003, the figures burgeoned to a staggering Tk60,400 crore in 2022, painting a portrait of financial distress writ large.

Behind these stark figures lies a tale of disparity, as different types of banks bear the brunt of this mounting burden. State-owned commercial banks (SCBs), once stalwarts of stability, witnessed their share of loan write-offs surge from 31% in 2003 to a startling 56% in 2015, before a slight reprieve in 2022. Conversely, private commercial banks (PCBs) saw their contributions rise steadily, commanding a lion’s share of 60% by 2022, a testament to the shifting sands of financial dynamics.

By combining the ranks of non-performing and written-off loans, the veil is lifted, revealing a stark reality. In 2020, for instance, an NPL rate of 8% belied the true figure, as the addition of nearly four percent of written-off loans unveiled the actual NPL rate of 12%.

The Harsh Reality of NPLs

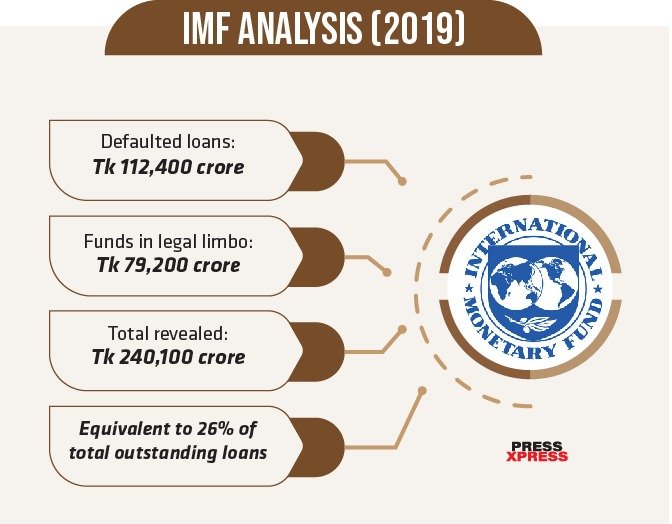

In 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) peered behind the curtain, undertaking a comprehensive analysis that encompassed a multitude of loan categories often overlooked in conventional assessments. From defaulted loans worth Tk112,400 crore to funds ensnared in legal limbo to the tune of Tk79,200 crore, the IMF’s calculations revealed a staggering total of Tk240,100 crore, equivalent to a daunting 26% of the total outstanding loans. Yet, this revelation laid bare a disconcerting truth—the reported NPL rate of 9.3%, a mere fraction of the actual magnitude, offered a distorted reflection of reality.

Recently, the Bangladesh Bank unveiled another layer of the NPL saga, shedding light on risky loans lurking in the shadows. With NPLs towering at Tk120,649 crore, alongside rescheduled debts and written-off loans, the specter of financial peril looms larger than ever. The culmination of these revelations paints a chilling tableau—a total NPL equivalent of Tk377,922 crore, a staggering 27.23% of the total outstanding loans, shattering illusions of stability and thrusting the banking sector into the crucible of crisis.

As Non-Performing Loans climb, Bangladeshi banks face provision woes, straining asset quality and capital maintenance. Accurate NPL estimation is crucial to avoid pitfalls. Underestimation masks financial fragility, risking solvency illusions. Some banks hover on insolvency’s edge, hidden until it’s too late.