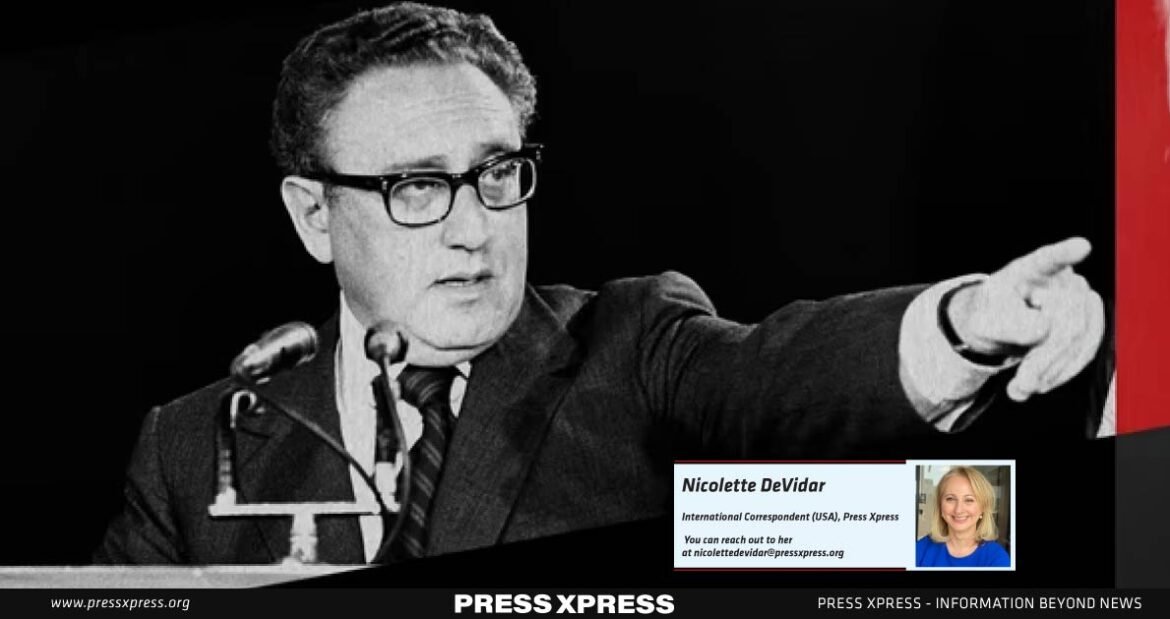

Henry Kissinger’s departure from the global stage generated many reactions. They are as controversial as his imprint on 20th centuries politics. Although serving as US Secretary of State for only eight years, his influence turned out larger than life. At closer look, it is comparable to the effect of a flagpole on which both ends of the political spectrum balanced each other off: Dictatorial and democratically elected governments around the world and various US administrations in Kissinger’s post-office times alike.

Kissinger introduced Realpolitik, a concept that defined the second half of the 20th Century US foreign policy to a large degree, but also much of his own worldview.

Realpolitik is a German word that can’t adequately be translated to English without losing some of the complexity of its concept. Just like Kissinger’s personality can’t be grasped in its full dimension without really understanding the word itself and all it entails.

Realpolitik captures Kissinger’s own essence: a tip of a Speer integrating the complexities of various realities of each stakeholder (or chess figure) at the moment of what is, without being clouded by ideologies; embedded in his particular lens through which he viewed the world, while simultaneously extracting the quint essence for what’s important for the US. All in one process.

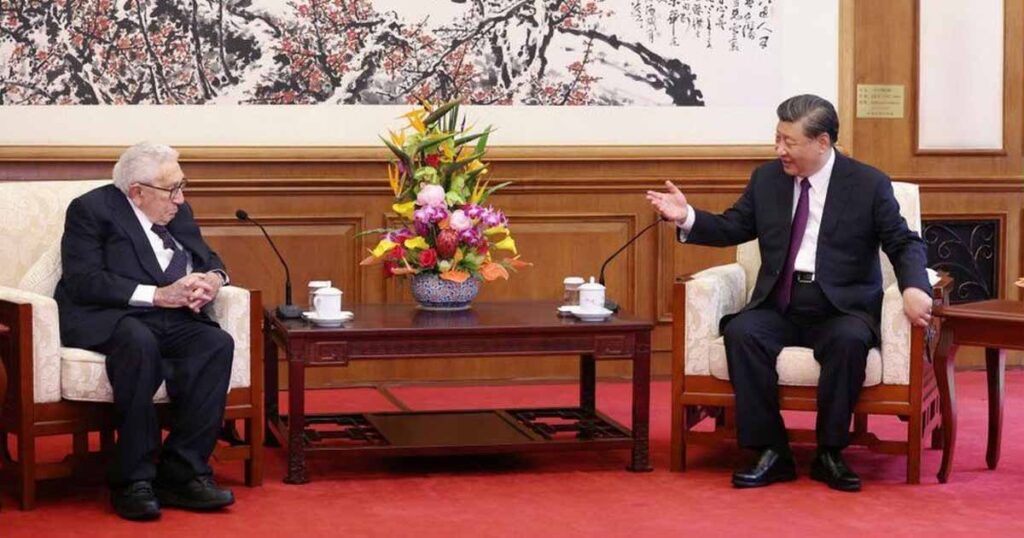

Whether championing “detente” with the Soviet Union or orchestrating secret negotiations in China, in his 100 year life span, his influence was underlined by erudite strategic thinking, cunning shrewdness, strong negotiation skills and his definition of Realpolitik.

From the moment he stepped foot into the world of politics, he demonstrated an ability to navigate complex geopolitical landscapes. He got America out of the Vietnam war. Played a pivotal role in shaping American foreign policy during the height of the Cold War while serving as the US National Security Advisor to President Richard Nixon. And masterminded a historic diplomatic breakthrough between the US and China ushering in a new era in US-China relations.

Then there is the other side: He ousted the democratically elected Chilean president Allende and supported Augusto Pinochet’s coup. Closely assessed political developments in smaller countries in Africa and South America using bombing raids and lethal tactics as diplomatic leverage. In 1971, Kissinger was the prime mover behind the US’s choice to back West Pakistan in its campaign against East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in his effort to bolster a friendly regime that could help engage China.

Kissinger didn’t shy away from supporting brutal dictatorships at times when he saw them useful to American interest, though “shuttle” diplomacy – a policy approach he practically invented — was at the core of Kissinger-ism. For some, he was too aggressive, for others, not aggressive enough.

His worldview seemed to always revolve around the theme of “restoring the world” , “renewing the world”, shaping the world order – with the central idea that nations abjured ideological conceptions and instead, operated in ‘Realpolitik’. This particular view — his lens — he projected onto US foreign policy.

A view that was widely shaped by his own experience and personal imprint from having grown up in a Germany in between wars:

where a focus on what is, without room for sentimentalities, was a defining cultural social element (before Nazi ideology took over); where a strict outlook on rebuilding from the pains of WWI – and later, amplified by the pains from WWII – constituted a focus nearly every family held.

It was an environment stripped of any sentimentality and emotions as all the energy by survivors needed to be mustered to focus on rebuilding new lives out of rubble.

Experiencing dramatic loss culminating in having to flee from your homeland in fear of being murdered are shock traumas that leave a deep imprint on the human psyche.

Survivors who experience what disastrous impacts can occur when environments change drastically overnight, find themselves more often than not in a constant state of tense observation to proactively stay in control. Kissinger is a perfect example.

His outlook: Better to play the chess figures than being played as one. With mortal threats constantly in view.

One could say, security is the center of foreign policy. But to someone who has experienced shock trauma, loss, persecution and mortal threats – it inevitably adds another dimension.

An approach evident throughout his political influence and thought process.

Our objective”, he wrote, “was to purge our foreign policy of all sentimentality”.

“The superpowers’, he wrote “often behave like trow heavily armed blind men … each believing himself in mortal peril from the other which he assumes to have perfect vision”.

“I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people”.

Kissinger’s world was a chess board. And he the skilled puppeteer. One who looked at the whole board, not just a part. Displaying a full range of Good and Bad in a single swipe.

The red thread: Skillful play of opposites – Kissinger’s life theme

Kissinger’s approach to stability was a skillful play and integration of opposites – in his strategic outlook as much as in the display of his personality. Everything about him was two-fold. (– Generally, a hallmark of stability.) Kissinger exemplified human complexity in full range, from savage to witty. And embraced all of it.

“Ignorant” is what he said to those who only saw one side. As much as he wrecked havoc in South America and other small nations, One-sided, Kissinger never was.

As diplomat, he conversed with figures along the entire spectrum of left and right, communism and capitalism, democracy and totalitarianism — and wasn’t afraid of engaging with either one of them.

Spiraling Up

In today’s vocabulary one could say, he used an inclusive approach to the whole chessboard. Something that can’t be said about politics today. In today’s climate around the world, the name of the game has become to reduce complexity to a single narrative, denying that another end of the spectrum exists and/or can contribute something to the stability of the whole.

The consequence is a world with increasingly polarized ends on both sides (left and right of the spectrum), who negate the existence of the other side of the chess board. Today, opposite views are often oppressed, censored, demonized or simply negated. Instead of inviting them to construe a more constructive climate, built on an understanding that stability needs opposites. It takes conscious efforts to invite opposite viewpoints to a discussion. Something to be lauded when it happens today.

While Kissinger’s approach can be easily judged, condemned or admired — it was deliberate. Whether good or bad, it was based on a vision. It involved deliberate thinking vs empty emotional reacting, or the plain impulse to oppose.

The end of thought

Kissinger-ism in the 20th Century was characterized by diplomacy and negotiation, rooted in geopolitics and an understanding of historical and cultural contexts. (Embedded of course by the unsentimental approach to life through his personal experience as discussed earlier.)

Few of these are visibly present in international dealings of today. In Western politics, we see instead a negation of previous administration policies as the new modus operandi. In lieu of vision. — It’s the end of thought.

Absence of vision leads to chaos. While vision always provokes pro and cons – (as it’s two-fold) – vision is a flagpole to hold space for the future to evolve.

In today’s complexity-driven environment, those flagpoles — aka visions (not ideologies) — are few. Mainstreaming by denying other points of views in favor of ideology or impulse to oppose has taken over making the overlapping grey area — the place where consensus can be found — where opposites can meet, inaccessible. Thus, we see more polarized societies driven by impulse raw emotional reactions vs a deliberate focus on addressing the issues of our time from a big picture perspective and with evolving consciousness.

Where opposites meet is really the place where things can happen. Think of a spiral: coming to a full circle is the beginning point of the next higher stage in human and earthly evolution.

Ironically, Kissinger’s influence on the global stage was marked by the Yom Kippur war. He departed during the Israel-Gaza war. In systems transformative terms, one could say, it’s coming full circle.