China has launched a high-profile summit to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive project designed to boost global connectivity and trade through Chinese investments in infrastructure development. World leaders, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, have convened in Beijing for this milestone event, occurring against the backdrop of escalating tensions between Israel and Hamas.

China’s ambitious BRI

The BRI, initiated by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, has attracted hundreds of billions of dollars in investment for the construction of bridges, ports, highways, power plants, and telecom projects across Asia, Latin America, Africa, and parts of Europe. Xi has characterized it as the “project of the century,” symbolizing China’s ascent as a global powerhouse. Nevertheless, it has faced growing skepticism, especially in Western capitals, where concerns about Beijing’s global aspirations prevail.

Critics have accused China of burdening developing nations with excessive debt through the initiative. Large-scale BRI projects have encountered environmental and labor issues, as well as corruption scandals, sometimes leading to public protests.

A decade into the BRI, Xi’s global infrastructure ambitions confront challenges. Chinese investment in BRI projects has waned as the country’s economy slows down. Recipient nations struggle to meet their debt obligations, partly due to global economic disruptions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine conflict.

Meanwhile, the United States perceives the BRI as a means for Beijing to expand its global influence at the expense of American power and has proposed its own infrastructure development investment program.

The Beijing summit has prompted heightened security measures, with road closures and a significant police presence, as leaders and delegations from around the world come together for this momentous occasion.

China’s BRI Fuels Infrastructure Worldwide

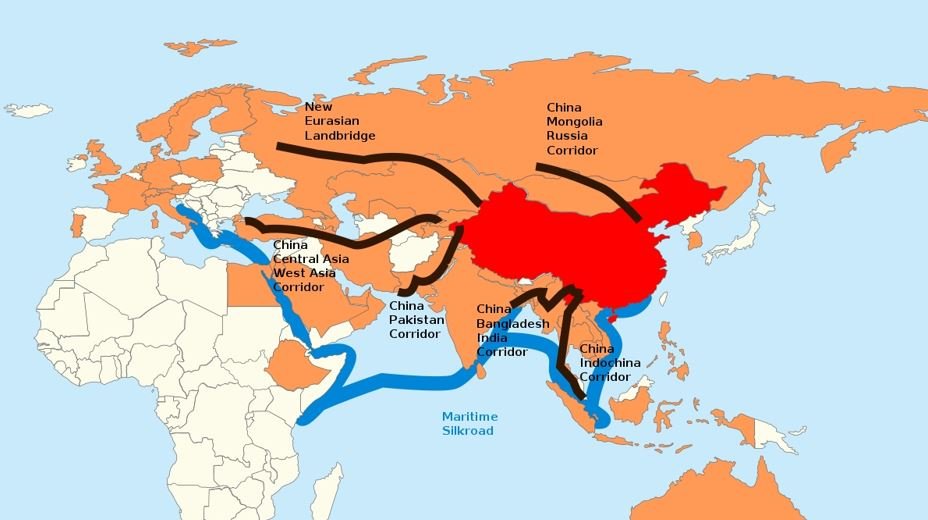

Originally envisioned as an overland “belt” and a maritime “road” connecting China with Europe and Africa, the BRI has funded infrastructure and energy projects across the developing world.

Supported by China’s development banks and state-controlled commercial lenders, Chinese construction firms have built extensive highways in regions from Papua New Guinea to Kenya, established ports in areas like Sri Lanka and West Africa, and provided power and telecommunications infrastructure across Latin America and Southeast Asia.

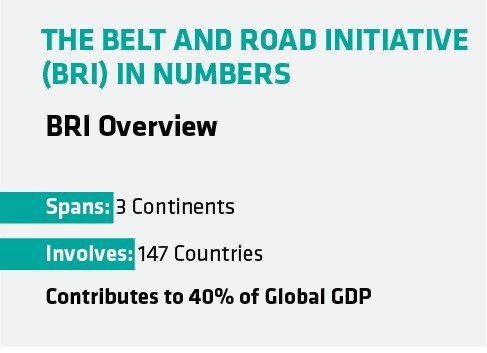

Beijing asserts that over 150 nations have engaged in cooperative agreements within the BRI framework, pledging to undertake more than 3,000 projects with an estimated mobilization of up to one trillion dollars in investments. Nonetheless, monitoring BRI financing remains intricate due to limited data transparency and the involvement of numerous financial entities.

According to research from Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, China’s primary development banks extended a minimum of $331 billion in loans to government borrowers in developing countries between 2013 and 2021. In the initiative’s inaugural five years, China, on average, outspent other major economies, including the United States, on financing overseas development projects, according to AidData, a research lab based at William & Mary in the United States.

Risks and criticism

While the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has played a vital role in offering essential funding to impoverished nations, drawing comparisons to the United States’ post-World War II Marshall Plan to reconstruct Europe, critics argue that it has come with its own set of drawbacks. Some of its projects have faced allegations of insufficient environmental and labor standards, while others have encountered recurring obstacles due to funding shortages or opposition on political grounds.

According to the Global Development Policy Center, Chinese-built fossil-fuel power plants release approximately 245 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. The same research revealed that Chinese development finance projects pose considerably higher risks to biodiversity and indigenous lands compared to projects financed by the World Bank. However, the primary concern revolves around the issue of risky lending, as critics accuse China of burdening low- and middle-income governments with debt levels that surpass their GDP capacities.

While claims that the Belt and Road Initiative serves as a comprehensive “debt trap” designed to gain control over local infrastructure have been largely dismissed by economists, they have tarnished the initiative’s reputation. This was particularly evident when Sri Lanka relinquished control of the Hambantota port to China after failing to meet its debt obligations.

More recently, experts suggest that China’s overseas lending portfolio has shifted toward supporting borrowing nations in financial distress, reflecting the evolving financial landscape and the challenges that countries face in repaying substantial loans to Beijing and other lenders.

BRI Faces Economic Challenges

Initially conceived, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) served as a means to direct China’s surplus capacity abroad and create fresh avenues for Chinese goods in international markets. However, as China’s economy experiences a deceleration, the once-ambitious program seems to be losing momentum, a trend that began even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

China is entering the second decade of the Belt and Road facing substantial economic challenges domestically. The anticipated post-COVID economic rebound has not materialized, and local governments are grappling with increasing debt linked to a property crisis.

The extent to which Beijing’s domestic economic challenges will impact its overseas lending in the long run remains uncertain, but there are indications of shifting strategies. Analysts have observed a departure from an emphasis on grand, often wasteful, multi-billion-dollar infrastructure projects towards smaller ventures with more favorable returns, particularly those involving renewable energy and digital technology.

China may also place greater emphasis on environmental concerns, improved social protections, and due diligence, especially as Beijing and its banks draw lessons from the project’s first decade.

Moreover, the BRI has spurred other countries to enhance their own efforts in supporting infrastructure projects in the developing world. In June 2022, leaders from the Group of Seven advanced economies pledged to allocate $600 billion in investment by 2027 to advance transformative projects aimed at narrowing the infrastructure gap between nations.

Just last month (September, 2023), the United States, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, France, Germany, Italy, and the European Union announced their collaborative plan to establish rail connections linking Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

Increasing China’s Clout Globality

According to Mr. Lavin, “I believe it serves as a valuable tool in Chinese diplomacy, strengthening relationships.” He adds, “It certainly enhances dialogues from Beijing’s perspective, but it might not necessarily foster a regional consciousness or a collective regional will to collaborate.”

While the running cost is estimated to be around US$2 trillion, the overall expenditure on the BRI is projected to reach as high as US$8 trillion over its lifetime.

Dr. Chong underscores that China’s capacity to invest in other nations, especially in developing regions, has significantly increased its global influence. “This has notably bolstered China’s international clout.”