The topic of religion-based politics has become an increasingly important issue in recent times in Bangladesh, unlike anything we have seen before in the country’s history. The emergence of organizations such as Jamaat-e-Islami and Hefazat-e-Islam, as well as their violent behavior and calls for bans, have raised concerns about the future of politics in Bangladesh. This is further compounded by the accumulation of power by religious political groups, the compromising position of the country’s main political parties, and the growing violence committed in the name of religion. As a result, people are questioning the reasons behind this phenomenon and its potential impact on the future of Bangladesh.

WHAT ARE THE REASONS FOR THE INCREASING INFLUENCE OF RELIGION IN POLITICS?

The answer to this question is being sought by many. In recent decades, Islamists have gained power in several countries around the world. One factor behind this trend is the collapse of the Soviet Union, which resulted in a decline in the popularity of socialism as a political ideal. Additionally, the foreign policy of the United States has played a role, as US policies in Afghanistan from the 1980s to the present day have directly or indirectly empowered Islamists. In some nations, Islamists have achieved power through democratic elections, while the equivocal stance of Western nations on the Palestine issue has helped increase their popularity among the general public. Moreover, the failure of secular governments and their leaders in numerous countries in meeting the basic needs of their populations, coupled with widespread corruption, has enabled Islamists to position themselves as a viable alternative.

YOU CAN ALSO READ: CARETAKER GOVERNMENT: DENT IN DEMOCRACY?

In Bangladesh, the growing influence of religion in politics can be attributed, in part, to increased social and economic ties with Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian nations (such as Malaysia). The number of Bangladeshis working in Middle Eastern countries has risen significantly, leading to closer social and economic relations with these nations. This has an effect among the rural people. Additionally, the expansion of Madrasah education in Bangladesh has played a role. Students who attend Madrasahs typically do not support groups outside of their religious beliefs. Each year, hundreds of thousands of students graduate from Madrasahs, and they are integrated into various sectors of society, where they often advocate for religious beliefs. Many Madrasah graduates are actively involved in religious politics, contributing to the growth of their political influence.

CURRENT SITUATION IN BANGLADESH

The rise of religion-based politics in Bangladesh can be attributed to various factors and processes, and although it has some support in Bangladeshi society, it is limited in scale. Recent elections have demonstrated that the level of support for Islamist parties is extremely low, with a combined vote share of less than 8 percent. While religion holds great importance and influence in social life, the people of Bangladesh do not view it as a political ideology and do not want to see religion used in politics. They do not see religious groups as legitimate representatives. However, violent incidents involving Jamaat-e-Islami or Hefazat-e-Islam or like-mined groups occur when there is political crisis. If clear ideas and concrete steps are not taken to address this situation, it could have long-term consequences for Bangladesh’s political landscape.

Some say that the radical right wing in Bangladesh have gained momentum in the current political vacuum as leftists and progressives are not as active as before, and the activities of the BNP and other opposition parties have dwindled. This has provided an opening for the right-wing to increase their presence in both urban and rural areas. However, another perspective is that the rise of religious right-wing parties is a result of power-centric politics without any clear ideological foundations. In this view, the right-wing has been able to expand their influence by taking advantage of the absence of a strong political opposition and by focusing on power rather than principles.

Some believe that the ruling Awami League in Bangladesh is providing various concessions to certain Madrasa-based parties and groups in an effort to suppress the opposition from the BNP and Jamaat. Previously, Jamaat-eIslami was a major rival to religious parties aligned with Qaumi Madrasas and Pir’s groups in the realm of religious politics. However, due to various factors, Jamaat no longer has a significant public presence and has been relegated to a state of voluntary exile. In their absence, ultra-conservative groups have attempted to fill the void. Despite their relatively small scale, religious parties have managed to carve out a position among the people and exert influence in the country’s political landscape.

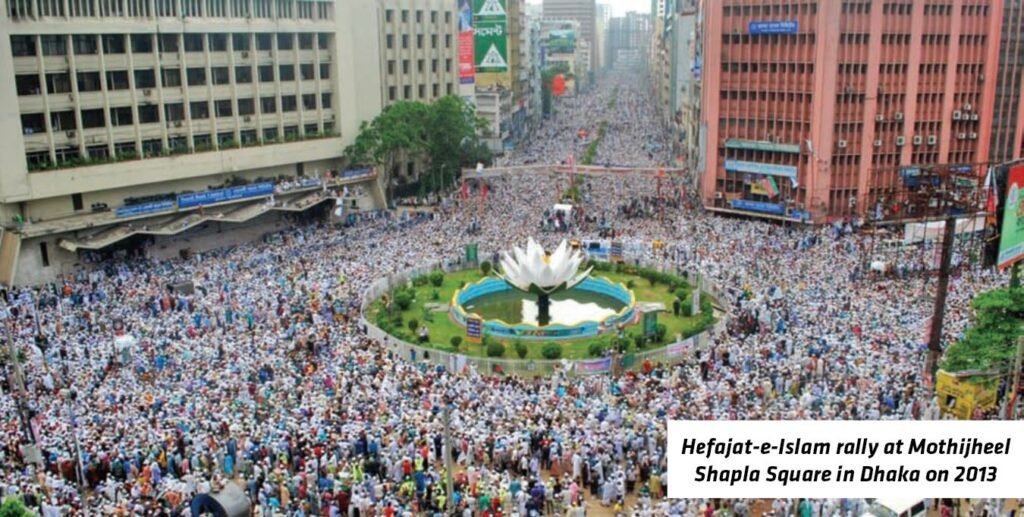

The first major demonstration of religious power in Bangladesh was seen on May 5, 2013, when Hefazat-e-Islami carried out a series of violent attacks in several areas of the capital, including Motijheel, Gulistan, Paltan, and Dainik Bangla. They set fire to various institutions, including shops and bank booths, and even cut down hundreds of trees in the middle of the road. After a day of chaos, they eventually settled at Shapla Chattar in Motijheel at night. Some political parties, including the BNP and Jatiya Party, encouraged the Hefazat workers with statements. However, the activists were eventually forced to vacate Shapla Square due to the all-out action of law-and-order forces later that night.

According to analysts, if the Hefazat activists had not been dispersed that night, they might have issued an ultimatum to Sheikh Hasina’s government to resign. The leaders and activists of BNP and Jamaat might have joined them, potentially leading to the fall of the government. However, a few days after the incident, the distance between the ruling party and the religious group unexpectedly decreased. The government began to provide various facilities to Hefazat leaders, and they eventually became silent.

Hefazat is among the religious parties that oppose the construction of a statue of Bangabandhu. Another significant religious group is the Islami Andolon, led by the son of the late Pir of Charmonai. This group often criticizes the government and opposes the construction of the sculpture of Bangabandhu.

Leaders of certain religious groups involved in various issues see an opportunity to build a strong position for themselves, especially in light of the inactivity of various anti-government forces. They are actively working to consolidate their position and increase their influence within society. As a result, they are gradually gaining strength and having an impact on the country.

Political analysts have a different perspective on this matter. They believe that the influence of religion on electoral politics in Bangladesh has been increasing since the 2001 elections. As a result, there has been a growing trend of religious groups joining politics. The political landscape has become polarized, with the major parties trying to keep the religious parties on their side for the sake of power. The religious groups are taking advantage of this situation by gaining various privileges from the state, which in turn increases their power and influence.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN RELIGION-BASED PARTIES ARE STRONG?

The inclusion of Islam as the state religion in Bangladesh has already raised questions about the equality of citizens, and the efforts of Islamists to push their agenda further in this regard only exacerbate the issue.

The inclusion of Islam as the state religion in Bangladesh has already raised questions about the equality of citizens, and the efforts of Islamists to push their agenda further in this regard only exacerbate the issue.

The objectives of religious parties are not fundamentally different from those of other political parties; they seek to gain power. However, unlike other political parties, religious parties do not acknowledge the sovereignty of the individual in promoting their political ideology to attain state power. The principle of individual sovereignty is a cornerstone of liberal democracy. Islamist organizations reject this principle, as they believe that recognizing individual sovereignty contradicts the sovereignty of God, making it unacceptable. This belief was once prevalent in the Christian community and still exists among some evangelicals in the United States.

One of the biggest downsides of a religious party in power is the potential for the erosion of equal rights for all citizens. When a state exhibits partiality towards a particular religion, it undermines the fundamental concept of equal citizenship before the law. This issue can arise not only when religious parties come to power, but also when they become dominant in politics. For instance, in 1974, religious parties in Pakistan forced the Ahmadiyya community to be declared as ‘infidels’ through the second amendment to the country’s constitution. In Bangladesh, Islamist parties have long demanded that the same be done, and this demand has recently been included in the 13-point demand for custody by such parties and organizations. Despite opposition from other parties and organizations, the demand is gaining momentum, as evidenced by the recent attack on the Ahmadiyya community in Panchagarh.

The inclusion of Islam as the state religion in Bangladesh has already raised questions about the equality of citizens, and the efforts of Islamists to push their agenda further in this regard only exacerbate the issue. As religious parties in Bangladesh gain strength, the main political parties seem to be retreating in the face of their pressure. The recent partial acceptance of the 13-point demand, including the consideration of custody claims and governance based on the Madina charter, is evidence of this. On the other hand, the BNP’s attempt to align with these organizations for political interest, without fully comprehending the implications of the custody claim, indicates a short-sighted approach by politicians who are not considering the long-term impact of religious parties on the state and social life of Bangladesh. So, in this backdrop, what will be the role of religious parties in the politics of Bangladesh in the future and what role will the constitution and law play?

THE FUTURE OF RELIGION-BASED POLITICAL PARTIES IN BANGLADESH

Many are questioning the role of religious parties and politics in the future of Bangladesh, especially regarding the fate of Jamaat-e-Islami. Those who oppose this brand of politics are seeking to address it through political means and are interested in understanding the actions they and the Bangladeshi government can take.

In dealing with religion-based politics, legal and constitutional considerations are typically the first point of reference. The Constitution previously prohibited religion-based politics until 1977, and Article 12 pledged to eliminate discrimination based on religion, political recognition of a religion by the state, misuse of religion for political purposes, and adherence to a particular religion in order to enforce the principle of secularism.

Although Article 12 was reintroduced to the Constitution, Article 38 took a different form. It stipulates that no one shall have the right to form or be a member of any association or organization that undermines religious, social, and communal harmony among citizens or attempts to discriminate against citizens based on religion, caste, sex, place of birth, or language. As a result of this change, the state cannot ban any political party on the basis of religion under this Constitution. This may be why the Prime Ministers and policy makers have repeatedly stated that religion-based politics will not be banned in Bangladesh.

WHAT SHOULD BE DONE TO COUNTER RELIGIOUS INFLUENCE IN POLITICS?

In order to address the rise of religious politics in Bangladesh, it is crucial to strengthen the democratic system. The historical emergence of Islamists in Muslim-majority countries, such as the rise of Hamas in Palestine from the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, has shown that when citizen participation in the political process is restricted and their rights are curtailed, Islamist groups can take hold. Algeria’s situation in the 1980s further reinforces this trend. In such circumstances, religious parties have demonstrated that the secular democratic system fails to guarantee the rights of citizens. Notably, religious parties in Bangladesh aim to foment antagonism and violence within established political parties. The undemocratic conduct of the major parties in Bangladesh has served only to benefit these groups. Thus, strengthening the democratic system is crucial, as democratic politics gives political rights to religious parties while confining religious politics within a limited scope.

To counter the rise of religion-based politics in Bangladesh requires not only strengthening the democratic system but also initiating a social movement. Political development in any country is not solely influenced by political parties, and this holds true for the rise of Islamist politics in Bangladesh.

Social, cultural, economic, and philanthropic organizations create an emotional landscape and a favorable environment for this type of politics, while education and mass media ensure its deep-seated permanence within society.

Despite the absence of an Islamist political party in Bangladesh from 1972 to 1978, various organizations worked towards this goal, and this process has continued and become widespread. Conversely, efforts by organizations to expose the negative aspects of Islamist politics have been limited. Religious groups have taken advantage of this situation to their benefit.

Attempting to deal with religious groups through legal and constitutional regulations or force while this situation continues within society is unlikely to succeed. Therefore, the second step is to initiate and sustain a social movement that requires significant reforms in the education system.

Finally, there is a little enthusiasm in the academic community of Bangladesh to engage in extensive discussions on religion and secularism, which have been taking place around the world for decades. This disconnection from new ideas and debates in the world of knowledge has led to a dearth of thought.

It is relevant to note that Islamist thinkers in various countries around the world have undergone changes in their thinking and ideological positions.

However, we do not see even a hint of this among South Asian Islamist politicians and their supporting intellectuals. If we do not create an environment conducive to reading, research, and fearless debate on the relationship between religion, secularism, politics, and society in Bangladesh, we will continue to be stuck in old ways of thinking. To wrap up, it is not realistic to expect a quick solution to the issues surrounding religion-based politics, religion-based parties, and the relationship between religion and politics. However, relying solely on the course of events is not the answer, and resorting to force is not a viable solution. Instead, finding a solution requires citizen activism and robust discussion. Through lively and vigorous debate, we may be able to discover a new path forward.