How Dr. Yunus Risks Turning Bangladesh into a Pawn of the US Deep State

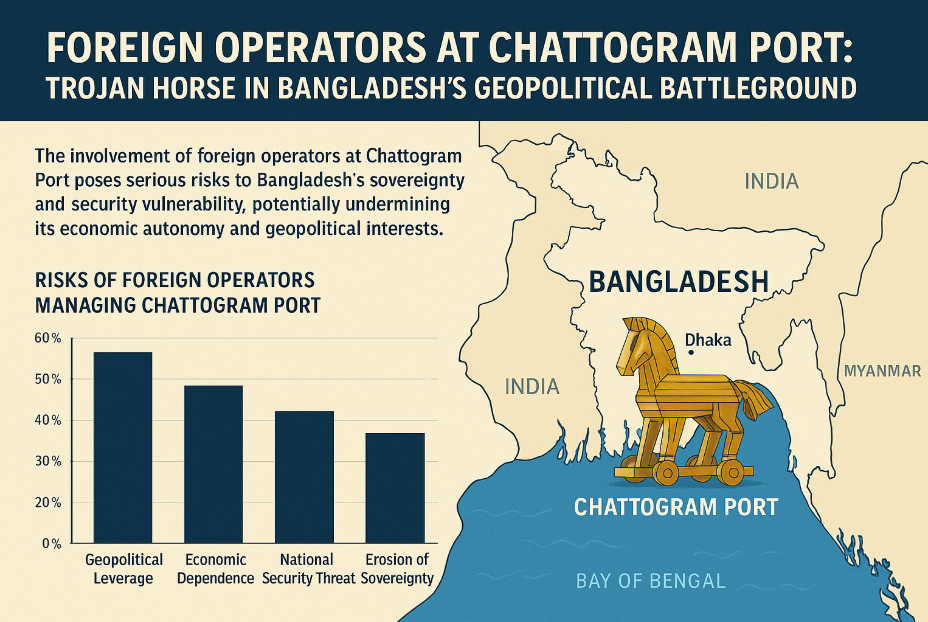

The recent announcement by the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) that three terminals – New Mooring Container Terminal (NCT), Laldia Container Terminal, and elements of the Bay Terminal of Chattogram Port, will be handed over to foreign operators by December. It has been packaged as a bold step toward so called “enhancing port management efficiency.” To the casual observer, it might sound like a harmless infrastructure upgrade, yet, beneath this polished rhetoric lies a geopolitical minefield.

The move cannot be separated from the political context in which it was made that with Dr. Muhammad Yunus now sitting as chief adviser in Bangladesh’s interim government, installed after the controversial removal of She

ikh Hasina, this decision appears less like an economic reform and more like a calculated maneuver to advance the United States’ deep-state ambitions in South Asia.

Indeed, for decades, the US has viewed Bangladesh as a strategic prize in the Indo-Pacific theatre. Its location on the Bay of Bengal provides a critical maritime gateway linking South Asia to Southeast Asia, and its newly expanded Exclusive Economic Zone offers access to untapped oil, gas, and mineral reserves. It menas, the aim is not merely to modernize a port, but to reshape Bangladesh’s geopolitical alignment, extract its vast natural resources, and recalibrate the region’s security balance.

A Security Gamble Bangladesh Cannot Afford

Ceding operational control of Chattogram Port to foreign operators poses multiple, interlinked risks. Placing this asset in foreign hands, especially those aligned with US strategic ambitions, is tantamount to surrendering Bangladesh’s front gate. And history is clear: once such control is ceded, reclaiming it is a costly and uphill battle. It compromises sovereignty by allowing external actors to influence berthing priorities, restrict or distort access to critical data, and potentially disrupt crisis logistics. The terminal’s systems record highly detailed information on cargo, shippers, and routing data that would be invaluable to foreign intelligence services. In a dispute, the ability to slow operations or adjust fees could be leveraged to exert pressure on national policy, while long concession contracts would limit Bangladesh’s capacity to reverse course or build domestic capabilities in the future.

These dangers are amplified by today’s geopolitical climate: the Myanmar border remains volatile, with some 1.5 million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and recurring cross-border clashes; naval activity in the Bay of Bengal is surging as Indo-Pacific alliances realign; and foreign intelligence agencies are expanding their footprint in strategic zones, with US-led QUAD ambitions looming large. In this environment, ceding control of the nation’s primary port is like inviting an unknown power into the nerve centre of national security—a gamble Bangladesh cannot afford.

The Insurgency Connection: A Hidden Agenda to Destabilise India

This issue extends beyond Bangladesh’s internal politics since India’s Northeast, known as the “Seven Sisters” (Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland), has long been a hotspot for insurgencies, separatist movements, and ethno-political unrest. Linked to mainland India by the narrow Siliguri Corridor, just 14.29 miles (23 km) wide, the region remains strategically vulnerable. While insurgency-related violence dropped by 70% in incidents and 80% in civilian deaths between 2013 and 2019, Manipur has seen a resurgence since May 2023, when clashes between Meitei and Kuki communities reignited militant recruitment and activity, often with the tacit or direct support of external actors seeking to weaken India’s grip on the area.

Against this backdrop, Dr. Muhammad Yunus’s statements to India’s NDTV on 7 August 2024 take on a deeper significance, “If you (India) destabilise Bangladesh, it will spill over all around Bangladesh, including Myanmar and seven sisters in West Bengal everywhere.” This conveys his critical intentions toward Indian territory, fueled by a political perception that he is closely aligned with Pakistan’s ISI. History offers precedent for channeling harm toward Indian territory: in 2004, under BNP rule, authorities intercepted a massive shipment of 10 truckloads of modern arms, including rocket launchers, at Chittagong Port’s Urea Fertilizer Ltd jetty. The cache was reportedly bound for the Indian separatist group ULFA.

Now on the ground, under a Yunus-led interim administration, closely aligned with US deep-state interests, the risk profile shifts dramatically. With foreign operators potentially controlling Chattogram Port terminals, the possibility of unscanned cargo, covert arms transfers, and clandestine military logistics grows substantially. Such a corridor could discreetly funnel resources to insurgent groups in India’s Northeast, achieving two strategic objectives for Washington: first, diverting India’s attention inward by reigniting domestic unrest; second, securing enduring US-friendly access to Bangladesh’s ports and Bay of Bengal maritime routes, thereby entrenching American strategic presence in the Indo-Pacific.

Resource Exploitation Disguised as Development

The Bay of Bengal is rich in oil, gas, minerals, and fisheries that sustain millions. Since resolving maritime disputes with Myanmar (2012) and India (2014), Bangladesh has secured about 118,813 square kilometres of maritime territory—covering a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea, a 24-nautical-mile contiguous zone, a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone, and parts of the continental shelf beyond. This expanse safeguards vital resources and strategic shipping lanes, making control over gateways like Chattogram Port a matter of sovereignty, not just trade.

But Bangladesh’s expanded maritime domain has also heightened its allure to resource-hungry powers. Framing the port handover as “efficiency improvement” conceals the real agenda: granting foreign operators the logistical control needed to extract and export these resources. Once terminals fall under foreign management, Dhaka’s ability to oversee or restrict exploitation will erode. The gains will leave the country; the environmental and strategic costs will remain at home.

Ignoring Domestic Capability

Proponents of foreign management at Chattogram Port point to promises of modern logistics, reduced corruption, and faster trade processing. Yet even if these gains materialise, they will come at the cost of deep strategic dependency. Once Bangladesh’s most critical maritime asset is integrated into the operational framework of a superpower’s corporate proxies, national leverage to resist external policy demands will diminish sharply. Operational efficiencies may be temporary; the strategic vulnerability will endure for decades.

The Bangladesh Investment Development Authority’s announcement raises critical questions. Were domestic companies given a fair chance to bid for these contracts? Has there been an independent security assessment of the prospective foreign operators? Are there undisclosed agreements that effectively predetermine control?

Bangladesh is not lacking in capability. Its logistics and shipping sector includes thousands of firms capable of managing port terminals, provided they receive adequate investment and access to modern technology. By sidelining these domestic operators in favour of foreign control, the government not only weakens national sovereignty but also erodes the very industrial base that could protect it.

This policy does more than compromise control of a vital asset, it undermines the domestic

Conclusion: Sovereignty Over Convenience

What Dr. Yunus proposes is not modernisation, it is surrender. Across the world, the US deep state has perfected a strategy: cloak geopolitical expansion in the language of development, take control of strategic infrastructure, and use it to reshape regional power balances. From Latin American ports to African mining hubs, the outcome is the same, local sovereignty eroded, foreign leverage entrenched.

Handing Chattogram Port management to a foreign entity is not an economic upgrade; it is a strategic forfeiture. In the Indo-Pacific, where US-China rivalry already defines the security landscape, this move would plant a permanent foreign foothold in the Bay of Bengal, destabilise India’s Northeast, and bind Bangladesh to an agenda it does not control. The precedent is clear, once such control is ceded, reclaiming it requires immense political, economic, and even military cost.

Dr. Yunus’s alignment with this playbook risks turning Bangladesh from a sovereign actor into a pawn in a larger geopolitical contest. This is not about faster cargo clearance or cleaner ledgers, it is about whether Bangladesh will retain the ability to decide its own fate.

The choice is stark: trade away independence for the illusion of foreign efficiency, or defend the nation’s strategic assets before they become instruments of someone else’s power. The Trojan Horse is already at the gates. Once it is inside, convenience will quickly become captivity.