Cambodia has emerged as an unlikely climate champion. Since signing the 2015 Paris Agreement, the Southeast Asian nation has positioned itself as a global advocate for emissions reduction, committing to carbon neutrality by 2050. The government’s 2020 Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and its recently approved Climate Change Strategic Plan 2024-2033 outline ambitious sustainability goals.

But while the Kingdom earns praise for its climate commitments, a growing number of critics argue that its flagship carbon credit farming program benefits wealthy industrialized nations at the expense of local farmers.

The Cost of Climate Action for Cambodian Farmers

As one of the world’s top 10 rice producers and exporters, Cambodia’s rice fields are now a key battleground for global carbon trading. The concept is simple: thousands of Cambodian farmers are being paid by foreign corporations—mostly from richer economies—to adopt greener farming methods in exchange for carbon credits that help polluters offset their emissions.

The reality, however, is far more complicated. The Cambodian Rice Federation (CRF) says that while the initiative looks good on paper, farmers aren’t getting a fair deal.

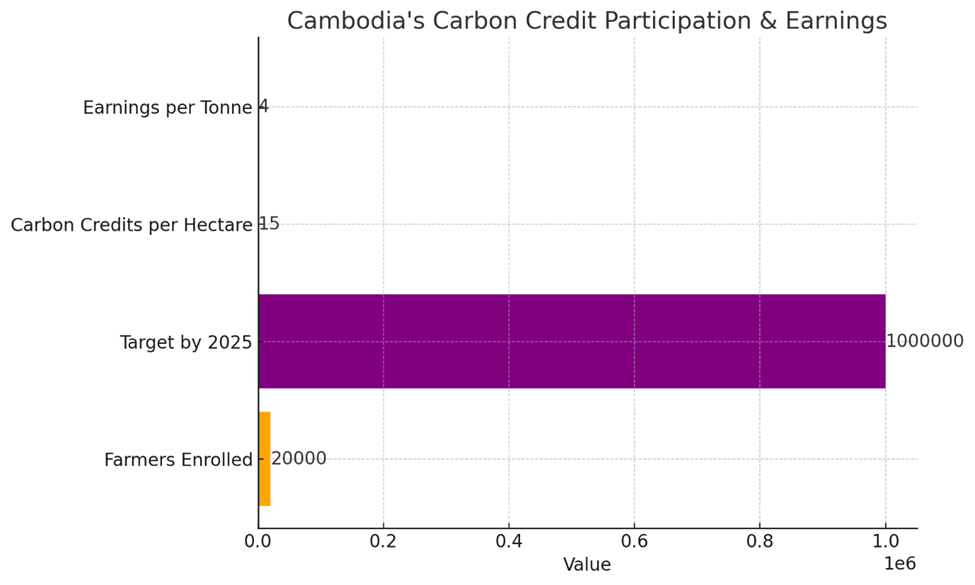

“For all the extra labor and money they pour into this, they’re earning just $4 to $10 per tonne of carbon credits,” says CRF President Chan Sokheang. “That’s nowhere near enough.”

A Billion-Dollar Industry, but for Whom?

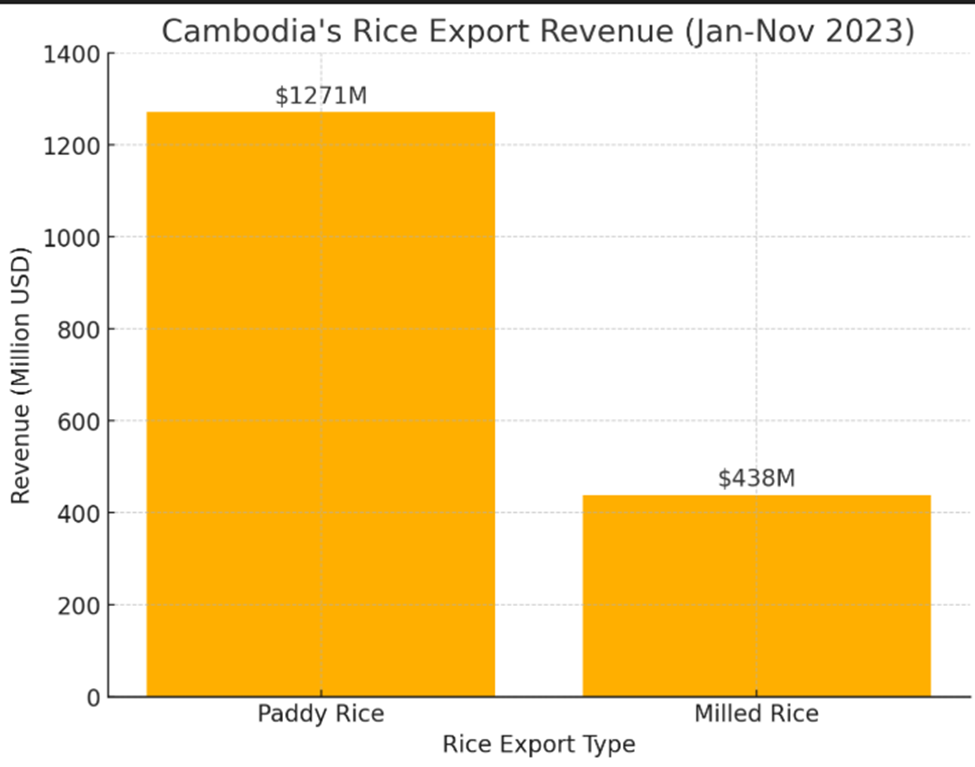

Agriculture accounts for 22% of Cambodia’s GDP, and rice is a major export. From January to November 2023, the country earned $1.27 billion from paddy rice and $438 million from milled rice, reflecting 16.42% and 3.97% year-on-year growth, respectively. China, Vietnam, and Thailand remain Cambodia’s biggest buyers.

But while the numbers look strong, many farmers feel the carbon credit system is rigged. To qualify, they must shift to Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD)—a labor-intensive method that reduces methane emissions by alternating between flooding and draining rice fields. They are also encouraged to produce biochar, a carbon-rich byproduct from burnt rice husks used to enrich soil or trade for credits.

The biggest foreign player in Cambodia’s carbon market is Japan’s Green Carbon, which recently struck a deal with Amru Rice, the nation’s leading organic rice producer, and the Royal University of Agriculture (RUA). The agreement aims to bring 20,000 farmers into the carbon trade, starting with 1,000 hectares before expanding to 1 million hectares.

“We are working with 20,000-30,000 small-scale farmers, but there’s still a long way to go,” says Green Carbon’s Yuri Maeono. The company has similar projects in Vietnam and the Philippines, with plans to capture over half of Cambodia’s irrigated AWD rice fields.

The Trade-Off: Climate Gains vs. Economic Realities

For all its ambition, the carbon credit system remains a tough sell for many farmers.

“It’s a lot of work, and the financial return just isn’t there,” says an agricultural economist who works with foreign governments but requested anonymity. “These farmers have used the same methods for generations. Why should they change if it doesn’t pay off?”

At COP28, Cambodia made high-profile commitments, including scrapping a coal-fired power project and avoiding hydropower developments on the Mekong River. The country has also pledged to plant one million trees annually and cut back on plastic waste. But the biggest question remains: will these climate policies actually benefit the people working the land?

Corporate Optimism vs. Ground Reality

Despite skepticism, Amru Rice sees potential in the carbon market.

“We’re launching with 650 farmers across 2,000 hectares, but we plan to scale up every year,” says Amru’s CFO Jonathan Lim. The company is set to register a carbon credit project in 2025, with a $1 million trial budget for its first year.

“We believe farmers will see the benefits over time,” Lim adds. “Eventually, this could expand beyond rice to other key crops like cashews and mangoes.”

Yet, as Cambodia pushes forward with its green ambitions, some farmers are choosing to stick with what they know. Satellite data from Thailand shows that Cambodia recorded nearly 700 rice stubble-burning hotspots this month—the highest in the region, despite a ban on the practice.

“Farmers are literally burning money,” says a foreign development expert. “But when you’ve farmed one way for centuries, change doesn’t come easy.”

A Work in Progress

For now, Cambodia’s carbon credit push is a bold experiment in progress. It could set a precedent for sustainable agriculture in emerging economies, or it could expose the flaws of a system that profits polluters more than farmers.

As one former diplomat put it: “Cambodia contributes a tiny fraction to global emissions, yet it’s doing more than some wealthy nations. That deserves some credit. But whether farmers see real benefits? That’s still up for debate.”