Inside South Africa’s glittering history as one of the world’s largest gold producers lies a stark reality—an underground world controlled by ruthless gangs, where thousands of illegal miners risk their lives to extract gold from abandoned shafts

South Africa’s gold mining industry, once a cornerstone of its economy, has witnessed a significant decline over the past three decades. This downturn has led to the proliferation of illegal mining activities, predominantly carried out by individuals known as “zama zamas.” These miners, often operating in abandoned shafts, face perilous conditions and are frequently under the control of organized criminal syndicates.

The Rise of Illegal Mining

The term “zama zama,” derived from the Zulu language meaning “take a chance,” aptly describes the plight of these miners. Following mass layoffs in the formal mining sector, many former miners turned to illegal mining as a means of survival. Estimates suggest that there are approximately 30,000 illegal miners in South Africa, organized by around 200 criminal syndicates.

These miners often spend extended periods underground, extracting gold from abandoned shafts. The operations are typically controlled by organized crime groups that provide protection and supplies in exchange for a significant share of the profits. The extracted gold is then sold on the black market, with a substantial portion smuggled out of the country. Between 2012 and 2016, over 34 metric tons of gold worth over $1.5 billion were smuggled to Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Illegal mining syndicates, often linked to organized crime, control the supply chain. These groups exploit laborers, provide weapons for protection, and traffic the gold. Syndicate leaders—frequently referred to as “kingpins”—remain elusive, with many living in affluent suburbs such as Sandton, Johannesburg, and Cape Town.

Economic Implications

Illegal mining poses a substantial economic threat to South Africa. The Minerals Council South Africa estimates that illegal mining costs the country approximately R21 billion ($1.1 billion) annually in lost sales, tax revenues, and royalties. This figure encompasses lost tax revenues, royalties, and sales. In Gauteng province alone, the economic hub of South Africa, there are an estimated 30,000 illegal miners operating. Across the country, the numbers swell to over 100,000 individuals, many of whom are former legal miners laid off due to the decline of the formal industry. Additionally, the illicit trade undermines the formal mining sector, deterring potential investments and contributing to the deterioration of mining infrastructure.

In the last decade, South Africa’s gold production has plummeted by 54%, from 132 metric tons in 2010 to 61 metric tons in 2020. Once the world’s leading gold producer, South Africa now ranks eighth globally, trailing behind countries like China, Russia, and Australia. This decline has rendered many mines unprofitable, leading to their abandonment and subsequent occupation by illegal miners.

Social and Security Challenges

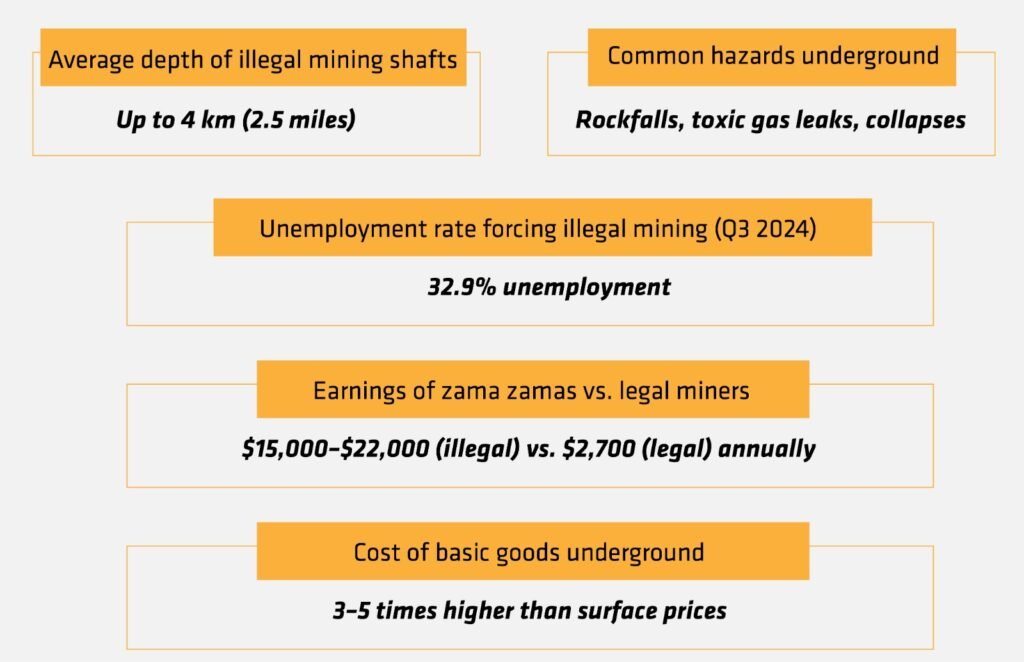

South Africa’s official unemployment rate stands at a staggering 32.9% (as of Q3 2024), forcing many to seek alternative livelihoods. For illegal miners, known locally as zama zamas, underground work offers earnings far surpassing formal employment. For example, zama zamas reportedly earn $15,000–$22,000 annually, compared to the $2,700 median wage of legal miners, BBC reported.

However, the risks are immense. The abandoned mines, some as deep as 4 km (2.5 miles), are riddled with safety hazards, including rockfalls, toxic gas leaks, and collapses. Fatalities are common, with certain areas being dubbed “zama zama graveyards” due to the accumulation of bodies underground. The New Yorker revealed, underground, miners rely on a makeshift economy. Basic goods, such as canned food, torches, and batteries, are sold at inflated prices—three to five times higher than surface market rates. Some shafts even feature red-light districts, with sex workers brought in by syndicates, further complicating the social fabric.

Environmental and Health Concerns

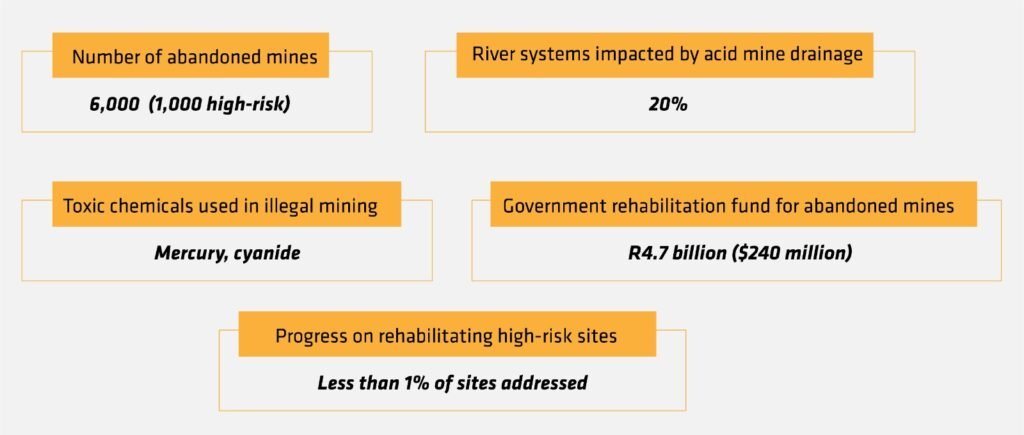

South Africa’s 6,000 abandoned mines, including 1,000 high-risk sites, pose severe environmental threats. Toxic chemicals like mercury and cyanide contaminate water sources, with acid mine drainage affecting 20% of the nation’s river systems. Improper waste disposal depletes soil quality, making land unfit for agriculture, while mining dust exacerbates air pollution, causing respiratory issues in nearby communities.

Moreover, the structural integrity of abandoned mines is often compromised, increasing the risk of collapses and accidents. The lack of safety protocols and equipment further exacerbates the dangers faced by illegal miners, resulting in frequent fatalities and injuries.

Crime Nexus: Another Dark Side of Illegal Mining

Illegal mining operations are intertwined with organized crime. Syndicates arm miners with pistols, shotguns, and semi-automatic rifles, escalating violence in mining areas. Local communities report frequent clashes between rival gangs, leading to casualties. In 2023 alone, police confiscated over 1,000 firearms and 35,000 rounds of ammunition in raids targeting illegal mining operations.

South Africa’s mining minister, Gwede Mantashe, has described the situation as “a parallel economy,” urging increased military and police interventions. Despite efforts, corruption within law enforcement enables the trade to persist, with reports of bribes exchanged for ignoring illegal activities.

Government Response and Policy Considerations

The South African government has acknowledged the severity of the illegal mining crisis. President Cyril Ramaphosa described the Stilfontein mine as a “crime scene” and emphasized the need for a coordinated response to tackle the issue. Law enforcement agencies have intensified operations against illegal miners, resulting in numerous arrests and the seizure of significant quantities of firearms, ammunition, and uncut diamonds.

However, experts argue that a purely punitive approach may not yield sustainable results. David van Wyk, a researcher at the Benchmark Foundation, suggests that decriminalizing and regulating artisanal mining could provide a more effective solution. By formalizing these operations, the government could ensure better working conditions, environmental compliance, and a new revenue stream through taxation.