The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson, three economists whose research examines the influence of political and economic institutions on a country’s prosperity.

Their work, grounded in data, seeks to understand how historical events, particularly European colonization, have contributed to vast disparities in wealth among nations today.

The Colonial Roots of Economic Inequality

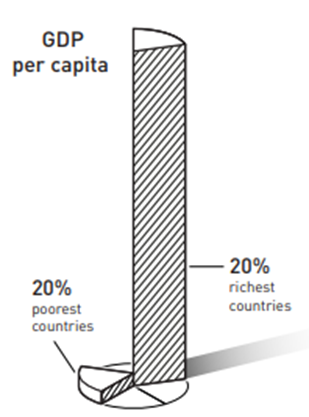

The data is stark: the richest 20% of countries have an average income per capita that is over 30 times higher than that of the poorest 20%, according to the World Bank.

The Nobel laureates argue that these disparities are not merely the result of geography or natural resources, but rather the quality of institutions inherited from the colonial period.

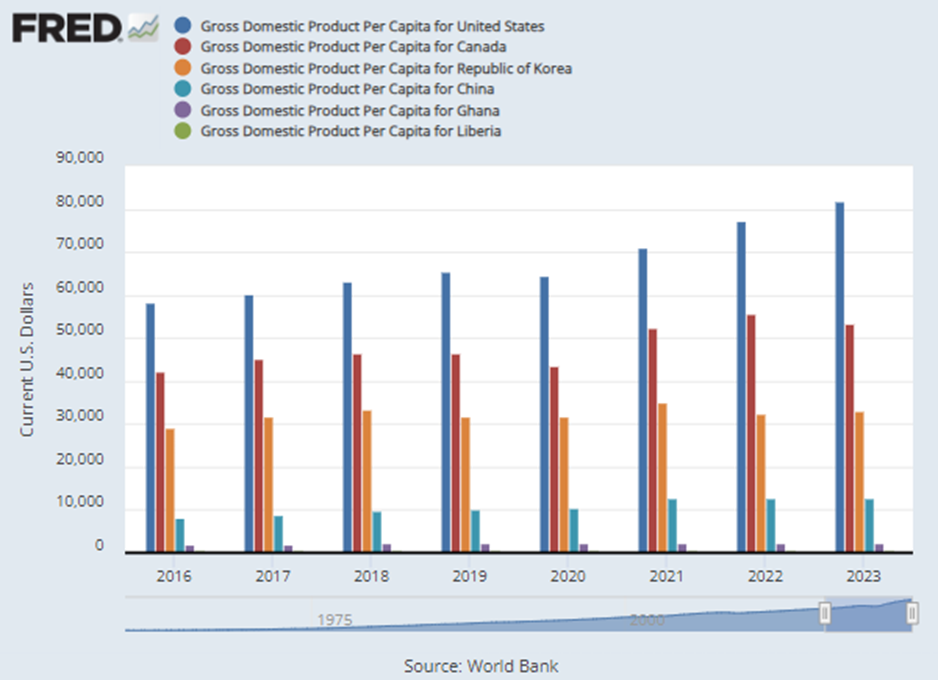

In regions where European colonizers found the climate favorable and disease burden low, they often established governance structures that mirrored those in Europe. These included protections for private property, political stability, and the rule of law—all conducive to long-term economic growth. For instance, the United States, where settlers created inclusive institutions, now enjoys a per capita GDP exceeding $70,000, placing it among the wealthiest countries globally.

However, in areas where settlers faced harsher climates and higher mortality rates—particularly in parts of Africa and South Asia—colonizers set up extractive institutions. These systems were designed to maximize resource extraction for the benefit of the colonial power, often at the expense of local populations. Today, nations that inherited extractive institutions tend to struggle economically. For example, GDP per capita is about $2,600 in Bangladesh and only $550 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, underscoring the long-term costs associated with extractive practices.

Inclusive vs. Extractive Institutions: A Key Determinant of Wealth

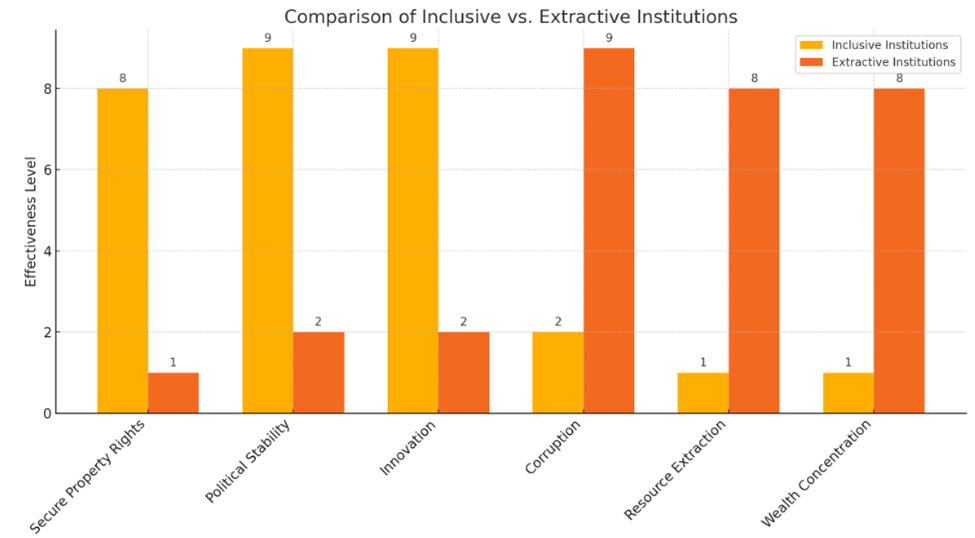

The laureates’ work draws a clear distinction between “inclusive” and “extractive” institutions, terms that describe how political and economic power is distributed. Inclusive institutions encourage investment and innovation, while extractive institutions prioritize the wealth of a select few, often at the expense of the broader population.

In inclusive systems, individuals have incentives to invest in their future because they enjoy security in property rights and freedom to participate in the economy. Countries like the United States and Australia rank highly in indices measuring political stability, regulatory quality, and ease of doing business—factors that contribute to their long-term economic success. According to the Global Innovation Index, both countries are also among the world’s top innovators, a direct result of their institutional frameworks.

Conversely, countries with extractive institutions face significant obstacles to growth. Without secure property rights or political freedoms, investment stagnates, and economies become vulnerable to corruption and exploitation. The Corruption Perceptions Index shows that nations with extractive institutions, such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe, tend to have high levels of corruption and low levels of economic freedom. In Venezuela, for example, GDP per capita has plummeted from over $10,000 in the early 2010s to under $4,000, illustrating the devastating impact of extractive governance.

The Lasting Impact of Colonial Choices

The Nobel laureates suggest that many of today’s economic disparities are rooted in institutional decisions made during the colonial era. For example, they point to India, where British colonial authorities established extractive institutions aimed at maximizing resource extraction rather than fostering local development. This legacy has had long-lasting effects: India’s GDP per capita remains relatively low compared to countries where more inclusive institutions were established.

To illustrate the link between institutional quality and economic performance, consider the case of Nigeria, where extractive institutions continue to dominate. While Nigeria is rich in oil, this wealth has not translated into broader economic prosperity. The country relies heavily on oil for export revenue—over 80% of its export earnings come from oil—leaving it vulnerable to price shocks and limiting economic diversification. This reliance on extractive practices has contributed to economic instability, with an average growth rate of only 1.8% over the past decade.

In contrast, Botswana, a former British colony in southern Africa, took a different approach. Following independence, it adopted inclusive institutions that promoted political stability and secure property rights. As a result, Botswana’s GDP per capita now exceeds $8,000, significantly higher than the regional average, illustrating the benefits of an inclusive approach to governance.

The Path Forward: Can Institutions Be Reformed?

The laureates’ work raises an important question: if inclusive institutions are essential for prosperity, why haven’t more countries adopted them? One reason, they argue, is that extractive institutions often benefit the ruling elite, who have little incentive to promote reforms that might weaken their power.

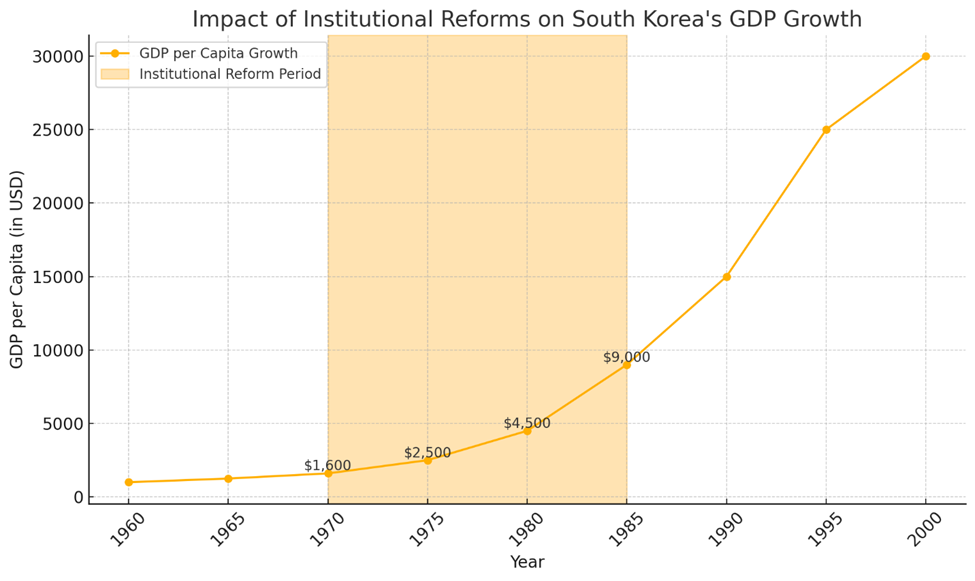

This persistence of extractive institutions is particularly evident in countries where elites can safely extract resources without facing significant opposition. However, history has shown that institutional change is possible. For example, South Korea, once characterized by extractive institutions, transformed itself in the late 20th century by adopting inclusive institutions. This shift has propelled the country to become one of the world’s leading economies, with a per capita GDP of over $30,000.

But institutional reform often requires external pressure or significant social movements to overcome entrenched interests. The researchers suggest that in some cases, threats of civil unrest or loss of power can prompt ruling elites to implement reforms. This underscores the importance of political dynamics in driving economic change.

The Role of Institutions in Bridging the Wealth Gap

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics brings attention to the role of institutions in shaping economic outcomes. By highlighting the connection between historical choices and modern-day disparities, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson offer a compelling explanation for why some nations thrive while others lag behind. Their work underscores the need for policymakers to focus not only on economic policies but also on the institutional frameworks that determine the “rules of the game” in any economy.

As global inequality remains a pressing issue, the insights from this year’s Nobel laureates provide a valuable framework for understanding how institutions can either support or hinder a nation’s prosperity. By fostering inclusive institutions that promote political stability, secure property rights, and broad economic participation, countries can build a foundation for sustained growth and greater economic equality.