Key highlights:

- In a joint announcement with the United Kingdom, Mauritius gained complete sovereignty over the isolated archipelago.

- The agreement allows the US military base on Diego Garcia to continue operations under a 99-year lease.

- The treaty aims to address the historical wrongs of forcibly displacing 1,500-2,000 Chagossians in the 1970s.

Diego Garcia is known as the “Footprint of Freedom” due to its strategic location in the Indian Ocean, which is within striking distance of Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, as well as its distinctive shape.

It was instrumental in the United States’ overseas operations following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, dispatching aircraft to Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2002, rendition flights arrived on the island, a claim that the United States had for years denied. However, the United Kingdom government affirmed the occurrence in 2008.

And, now having a fresh dimension over the UK’s decision to hand over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, finishing more than five decades of sour conflict over Britain’s last African colony. The deal represents a pivotal moment for both nations and is deeply tied to geopolitical strategies and historical injustices involving the forced displacement of Chagossian islanders.

This development follows years of negotiations and international pressure, most notably from the United Nations and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). However, the agreement retains the US military base on Diego Garcia, a strategic asset in the Indian Ocean, which will continue its operations under a 99-year lease. The UK will provide a package of financial support to Mauritius, including annual payments and infrastructure investment. Mauritius will also be able to begin a program of resettlement on the Chagos Islands, but not on Diego Garcia

“This is a seminal moment in our relationship and a demonstration of our enduring commitment to the peaceful resolution of disputes and the rule of law,” the statement from UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Mauritius Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth read.

The leaders also said they were committed “to ensure the long-term, secure and effective operation of the existing base on Diego Garcia which plays a vital role in regional and global security”.

The treaty will also “address wrongs of the past and demonstrate the commitment of both parties to support the welfare of Chagossians”.

The Historical Context

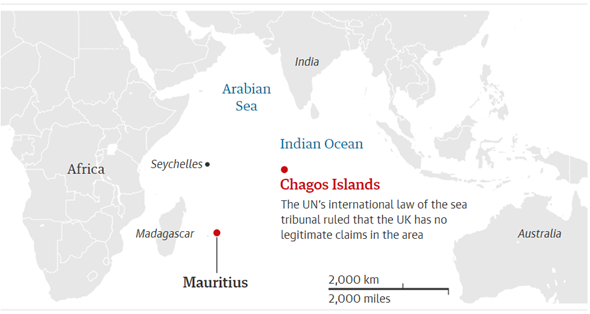

The Chagos Archipelago, including Diego Garcia, was separated from Mauritius by the UK in 1965, three years before Mauritius gained independence. The UK created the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) and leased Diego Garcia to the United States in 1966 for the construction of a military base in return for a $14m discount on Polaris missiles. This agreement came at the expense of around 1,500 to 2,000 Chagossians, who were forcibly removed from their homes in the early 1970s, sparking decades of legal battles and protests.

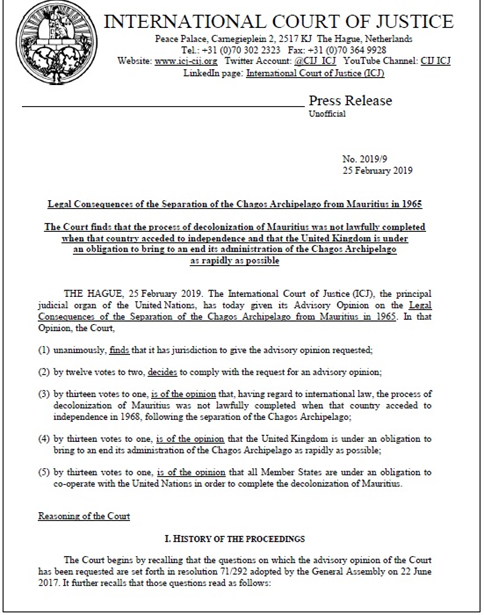

Over the years, international opinion shifted in favor of Mauritius. In 2019, the ICJ issued an advisory opinion that the UK should cede the Chagos Islands, declaring the detachment of the islands illegal. A subsequent UN resolution, endorsed by 116 member states, gave the UK six months to return the territory, yet the process stalled. Despite the UN vote, the UK refused to comply, citing the importance of the Diego Garcia military base, which it had leased to the United States in 1966 for defense purposes. The base plays a crucial role in regional and global security, particularly for US operations in the Middle East and Indian Ocean. The UK argued that returning the islands to Mauritius could jeopardize these strategic interests.

Brexit further isolated the UK, as many European countries and African nations began to align against its stance on decolonization. In 2021, Mauritius achieved another legal victory. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) tribunal ruled in favor of Mauritius, affirming that the UK had no sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. The tribunal’s decision reinforced the ICJ’s 2019 ruling and further eroded the UK’s standing on the international stage.

Mauritius’ Prime Minister, Pravind Jugnauth, reflected on the protracted struggle, stating, “We were guided by our conviction to complete the decolonization of our republic.”

A Deal Rooted in Geopolitical Strategy

The agreement comes at a time of growing geopolitical competition in the Indian Ocean region, where Western powers, China, and India all vie for influence. The Diego Garcia base has been instrumental for US operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and its future security was paramount in ensuring the deal moved forward.

The negotiations that culminated in the agreement reached on Thursday were initiated by the previous UK government. But the timing of this breakthrough is indicative of a growing sense of urgency in international affairs, particularly in relation to Ukraine. The United Kingdom is eager to eliminate the Chagos issue as a barrier to securing more global support, particularly from African nations, as the possibility of a second Trump presidency looms.

Both UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Mauritian Prime Minister Jugnauth emphasized the importance of the military base in maintaining regional and global security. The joint statement underscored their commitment to the “long-term, secure, and effective operation of Diego Garcia,” which will now operate under a 99-year lease.

US President Joe Biden also lauded the agreement, calling it a “clear demonstration that through diplomacy and partnership, countries can overcome long-standing historical challenges to reach peaceful and mutually beneficial outcomes.”

Chagossian Displacement and Reactions

The Chagossians, many of whom are scattered across Mauritius, the Seychelles, and the UK, have voiced mixed reactions to the agreement. The deal includes provisions for financial support and a resettlement program, allowing some Chagossians to return to the archipelago—except for Diego Garcia, which will remain off-limits due to its military use.

For many Chagossians, this agreement represents a bittersweet victory. Isabelle Charlot, a second-generation Chagossian, expressed optimism to BBC, saying, “Plans for resettlement would mean a place that we can call home—where we will be free.” However, others are less convinced. Frankie Bontemps, another Chagossian, voiced his dismay to BBC, stating, “We remain powerless and voiceless in determining our own future and the future of our homeland.”

Critics like Clive Baldwin, senior legal advisor at Human Rights Watch, have slammed the agreement, arguing it continues to marginalize the Chagossians. Baldwin noted, “It does not guarantee that the Chagossians will return to their homeland, appears to explicitly ban them from the largest island, Diego Garcia, for another century, and does not mention the reparations they are all owed to rebuild their future.”

The UK has also pledged to set up a trust fund to support the Chagossian community, but the deal has left some feeling excluded from the decision-making process. Chagossian Voices, a community organization in the UK, criticized the lack of consultation, stating, “Chagossians learned this outcome from the media and remain powerless and voiceless in determining our own future.”

Lastly, as the two nations finalize the treaty, the UK’s role in the Indian Ocean, the future of Diego Garcia, and the Chagossian people’s rights will remain key areas of focus. While the deal ends one chapter of colonial history, its geopolitical and humanitarian ramifications will continue to unfold for years to come.