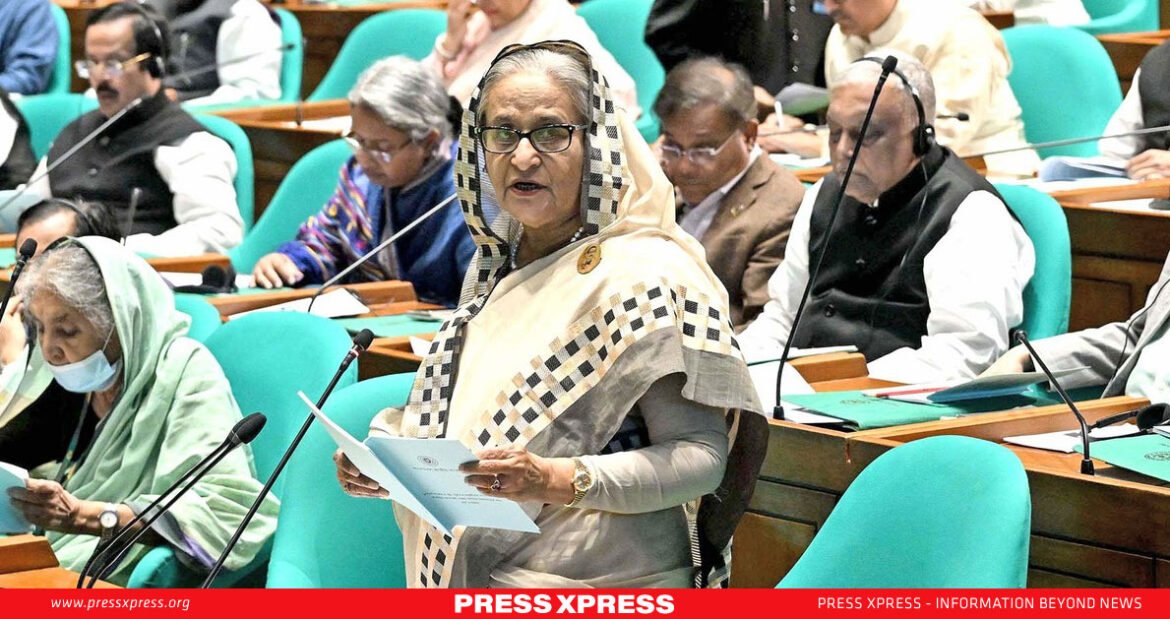

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina endorsed a budget provision to legalize black money, emphasizing its integration into the legitimate financial system. During a discussion at the Awami League office in Dhaka, she likened this process to baiting a hook, noting the initial nominal tax followed by regular payments. The proposed 2024-25 budget reintroduces the whitening of investments, including black money and undisclosed assets, through a 15% tax.

This decision offers amnesty for undisclosed assets, acknowledging that many countries adopt similar measures to address unreported assets. It aims to enhance compliance and combat money laundering, addressing calls from the business community and general populace. Black money is often kept outside the national economy, yields little benefit, and tends to go abroad.

You Can Also Read: GOVERNMENT MAY MOVE ON BLACK MONEY WHITENING SCHEME

The government urges individuals to declare undisclosed assets and adhere to tax regulations, offering immunity from tax inquiries for those who comply with the 15% tax between July 1, 2024, and June 30, 2025. This includes legalizing land, flats, and apartments by paying specified taxes based on the property’s area.

Highlighting her administration’s success, Sheikh Hasina contrasted the Tk62,000 crore budget of the last BNP regime and Tk68,000 crore under the caretaker government with her proposed budget of Tk7.97 trillion for FY 2024-25. This reincorporation of black money legalization after a four-year hiatus aims to integrate surplus funds into the formal economy, addressing economic realities and promoting financial transparency.

An Analysis of Past Trends and Future Implications

Under the new provision, taxpayers can pay a fixed tax rate for immovable properties such as flats and land, and a 15% tax on other assets, including cash, without facing any scrutiny from authorities, regardless of existing laws. This opportunity to legalize black money will remain available until June 2025.

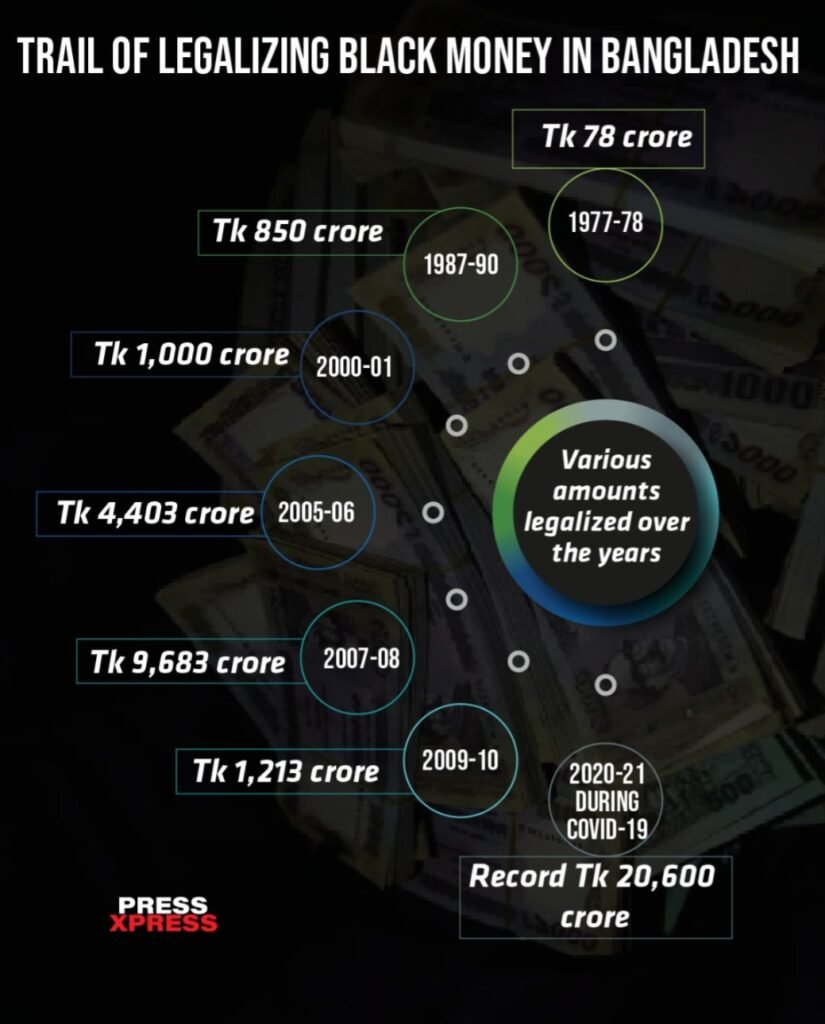

Data from the National Board of Revenue (NBR) indicates that nearly Tk45,522 crore was legalized between 1972 and 2022, yielding Tk4,641 crore in taxes. A record Tk20,600 crore was legalized in 2020-21 under a similar amnesty, generating Tk2,064 crore in taxes for FY21. In 2006-07, the caretaker government allowed black money to be legalized with a penalty, resulting in Tk9,682 crore being brought into the legal economy.

The exact amount of black money in Bangladesh remains unknown. However, the Bangladesh Economic Association estimates it could be as high as Tk13,253,500 crore, according to Prof. Aynul Islam, the association’s general secretary. A World Bank report published in April criticized the existing government policies for legalizing undisclosed wealth, arguing that such measures demotivate honest taxpayers and encourage tax evasion while failing to generate significant revenue.

Black money has plagued South Asian economies since the colonial era, fueled by activities like drug trafficking, smuggling, gambling, and corruption. A 2018 IMF study estimated that the shadow economy in Bangladesh accounted for over 30% of GDP, averaging 33.59% from 1991 to 2015. In contrast, a 2013 government-commissioned study found that the underground economy’s share of GDP had risen from 7% in 1973 to 62.75% in 2010. The IMF study focused primarily on legal economic activities, excluding illegal pursuits like prostitution and gambling, as well as informal household activities.

From Grey to White: Bangladesh’s Recurring Approach to Legalizing Black Money

The black or underground economy encompasses various terms such as hidden, shadow, grey, cash, unofficial, informal, and undisclosed economy. According to the IMF, it comprises all economic activities concealed from official authorities due to monetary, regulatory, and institutional reasons. Monetary factors include evading tax payments and social security contributions, while regulatory factors involve avoiding government scrutiny or regulatory burdens. Institutional factors stem from weaknesses in anti-corruption enforcement, political institutions, and the rule of law. The presence of a black economy distorts tax systems and leads to inaccuracies in measuring macroeconomic variables. Policies based on flawed measurements often fail to yield desired outcomes, exacerbating poverty and inequality while negatively impacting the quality of public goods and services.

Bangladesh is distinct in its recurring approach of allowing individuals to whiten black money, despite its questionable efficacy. Over the years, various amounts have been legalized: Tk78 crore in 1977-78, Tk850 crore from 1987-90, Tk1,000 crore in 2000-01, Tk4,403 crore in 2005-06, Tk9,683 crore in 2007-08, Tk1,213 crore in 2009-10, and a record Tk20,600 crore in 2020-21 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Except for the spike in 2020-21, these amounts are minimal compared to the estimated size of Bangladesh’s black economy.

A 2015 IMF report estimated the shadow economy at approximately Tk4,532.71 billion. A 2012 finance ministry report suggested that black money could be between 45-85 percent of Bangladesh’s GDP. Both reports indicate significant sums are hidden in the shadow economy, generated by and fueling further crime and corruption. This creates an invisible cycle with devastating social costs.

Examining the Impact of Black Money in Bangladesh

Historically, black money in Bangladesh stems from widespread corruption and bribery within the political and bureaucratic systems. This deep-rooted issue has led to public officials across various sectors amassing wealth far beyond their declared incomes. To combat the influence of black money, it’s crucial to strengthen anti-corruption institutions and address the known sources of illicit funds rather than legalizing them through lenient laws.

In the fiscal years 2007-2008 and 2008-2009, under the military-backed caretaker government, Tk9,682.99 crore of black money was legalized, the highest amount in Bangladesh’s history. In FY21, individuals could legalize their money by investing in the stock market or as cash, bank deposits, and savings certificates, with a mere 10% tax. Additionally, investments in land and flats were allowed, with tax rates based on location and size.

Impact and Analysis:

- Black money generated by and fueling further crime and corruption

- Poor compliance and lack of trust in tax authorities

- Honest taxpayers frustrated by additional investigation

- Evaders not scrutinized, demoralizing taxpayers

During this period, professionals like doctors, engineers, and businessmen took advantage of this opportunity. Despite the frequent availability of such schemes since Bangladesh’s independence, these initiatives typically failed to gain traction due to the scrutiny of undisclosed money sources by government agencies. To address this, the NBR amended the law in 2020, ensuring no questions would be asked about the sources of black money during or after the legalization process.