Key Highlights:

- The Dhaka slums, house 6.33% of the urban population

- Most rooms in the slums lack ventilation

- In 2021, the government provided newly constructed flats to 300 low-income families previously living in slums, enabling them to access civic amenities

Addressing the housing challenges faced by low-income communities in Dhaka is crucial for creating a more equitable and sustainable urban environment. To tackle these issues, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has pledged that even laborers will be able to live in apartments, highlighting the government’s effort to make Dhaka slum-free.

You Can Also Read: A NOBLE INITIATIVE FOR SLUM-DWELLERS

The Prime Minister made this promise during the launch of construction on the Bangabazar market and 3 other development projects on Saturday, May 25. By replacing informal settlements with structured, low-cost housing, Dhaka aspires to set a precedent for urban development that is both inclusive and sustainable, paving the way for a future where every citizen has access to safe and secure housing.

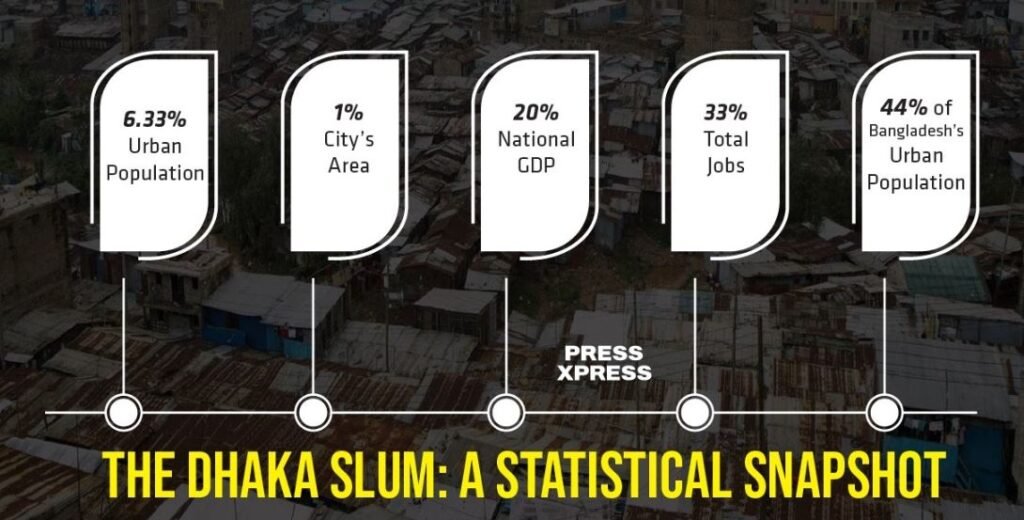

The Dhaka slums, which house 6.33% of the urban population, occupy only 1% of the city’s total area. Every day, approximately 1,000-2,000 people migrate to Dhaka in search of livelihood opportunities. Dhaka contributes to one-fifth of the national GDP and offers one-third of all jobs, has become a magnet for rural migrants.

As a result, Dhaka has transformed into a primate city, housing nearly 44% of Bangladesh’s urban population. This continuous influx has overstressed the city’s infrastructure, making it difficult to meet the basic living requirements of its low-income residents. Vulnerable groups are often forced to live in congested slums.

The Daily Struggle in the City’s Slums

Most rooms in the slums lack ventilation. A small area allows for 2-3 people to sit face-to-face, with a semi-double bed and a meat shelf occupying most of the space. The Kallyanpur Pora (Burnt) Basti is named due to being ravaged by fire partially or completely 8 to 10 times in the last 30 years. The most recent blaze in 2023 damaged over 300 rooms.

At least 3,031 families living in 10 blocks on a 17-acre plot owned by the House Building and Research Institute (HBRI) live in constant fear of fire. A 2021 study highlighted that living conditions in Dhaka Slum are substandard, with limited household resources, inadequate public goods, and poor-quality civic amenities.

In 2022, the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (URP) at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) presented a policy brief indicating that many of Dhaka Slum are located near hazardous industries, water bodies, and garbage sites.

Urban Poor Left Out of Housing Loans

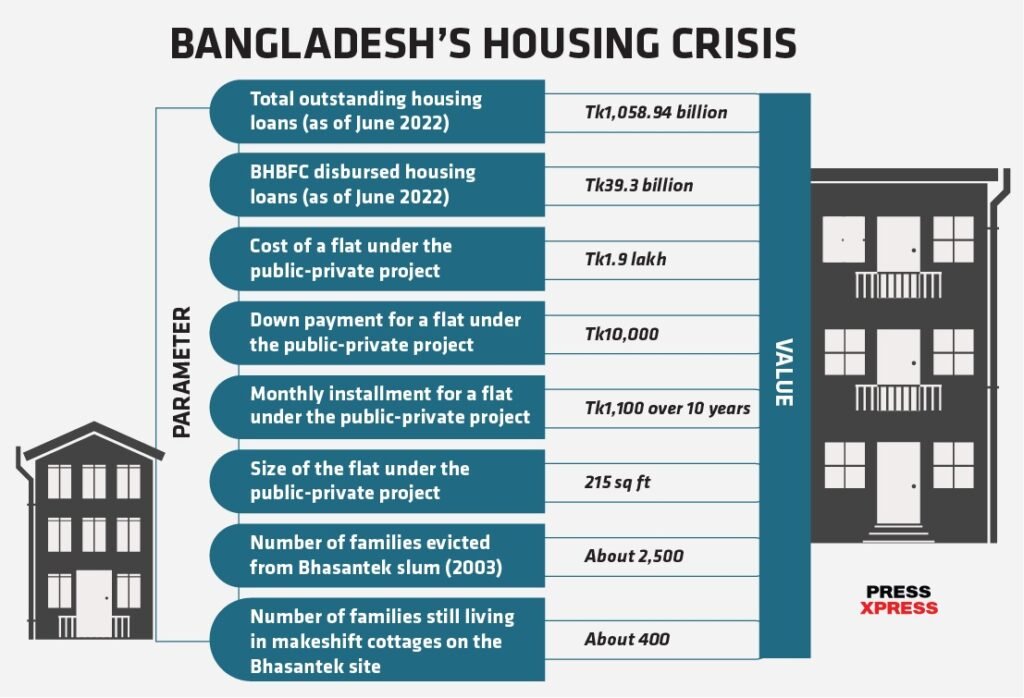

The Bangladesh House Building Finance Corporation (BHBFC), the sole public housing finance entity, addresses the housing crisis. By June 2022, total outstanding housing loans were Tk1,058.94 billion, with BHBFC disbursing Tk39.3 billion, and private entities providing the rest. BHBFC does not finance housing for the urban poor in Dhaka, Chattogram, or Sylhet Metropolitan cities.

Private banks and housing finance companies also do not offer schemes for the poor. The government has two housing projects for lower-income groups in Dhaka: The Bhasantek Rehabilitation Project and Rajuk’s Uttara Apartment Project.

North South Development Limited, responsible for Bhasantek, sold apartments to wealthier individuals instead of slum dwellers. A 2019 report showed no low-income individuals owned flats under the Uttara project. The Bhasantek project, launched in 2003, evicted about 2,500 families from the Bhasantek slum. None acquired the flats, and about 400 families still live in makeshift cottages on the site.

The public-private project offered a 215-sq ft flat for Tk1.9 lakh, with a down payment of Tk10,000 and monthly installments of Tk1,100 over 10 years.

Pockets of Progress Amidst Prevailing Problems

Despite the bleak situation, there are small glimmers of hope. In 2021, the government provided newly constructed flats to 300 low-income families previously living in slums, enabling them to access civic amenities. Each 672-square-foot flat, comprising a drawing room, kitchen, and separate bathrooms, has a daily rent of Tk 150 and a monthly rent of Tk 4,500.

The Ministry of Housing and Public Works financed and implemented this project in Mirpur 11, Dhaka. This marked the first phase of relocating slum residents to better housing. The project, costing Tk 148 crore, includes around 10,000 flats. In its second phase, 1,001 more families received flats.

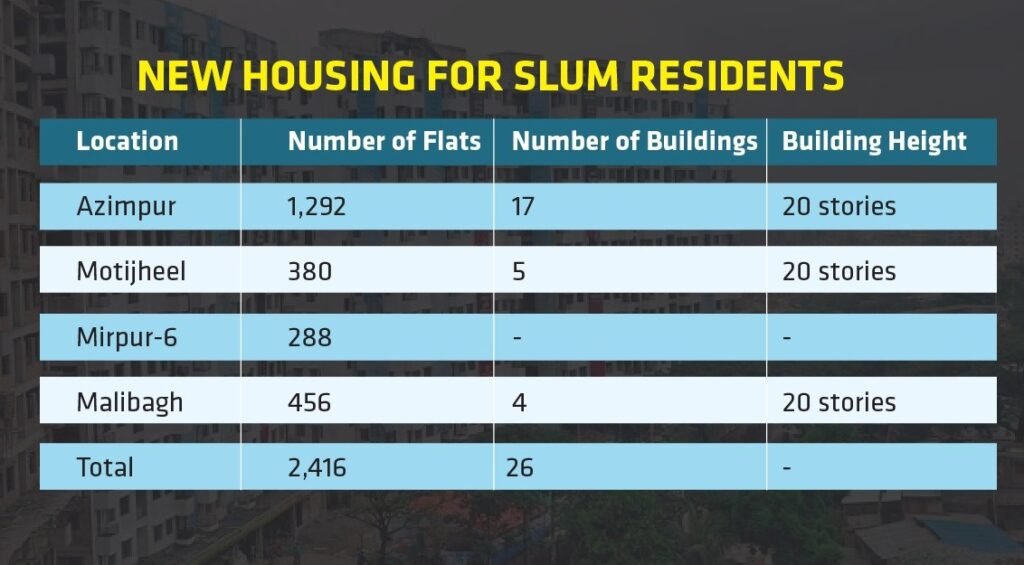

Beyond housing projects for slum residents, the Prime Minister inaugurated 2,474 flats in Azimpur, Motijheel, Mirpur, Malibagh, and Tejgaon areas for government employees posted in Dhaka. Specifically, Azimpur has 1,292 flats in 17 20-storey buildings, Mirpur-6 has 288 flats, Malibagh has 456 flats in four 20-storey buildings, and Motijheel has 380 flats in five 20-storey buildings.

From Slums to Sanctuaries: ‘Ashrayan’ Brings Housing Revolution

As skyscrapers replace slums, villagers without homes are being provided brick houses through the ‘Ashrayan’ initiative. Each beneficiary receives a two-decimal plot of land and a semi-furnished, two-room house equipped with free electricity, a kitchen, a bathroom, and a shower.

Both spouses’ names are registered for ownership of the house and land. Extensive tree planting efforts are underway in project areas, and one tube well is provided for every ten families to ensure access to clean drinking water and prevent waterborne illnesses. Community clinics will also be built to address healthcare needs.

This initiative stands as the world’s largest endeavor to grant free housing to the underprivileged, aiming to integrate them into society. In the first two phases of the project, 183,003 homes have already been allocated, with the majority given as a gift during the Mujib Borsho celebration by the prime minister in 2021-22. An additional 65,674 houses have been constructed and await distribution.

In the labyrinth of Dhaka’s urban landscape, where slums stand as stark reminders of inequality, a beacon of hope emerges. As the city grapples with the weight of its expansion, government initiatives offer not just shelter, but a sanctuary for those long relegated to the margins. Through concerted efforts led by the government and supported by communities, the narrative of urban poverty is being rewritten.