- The Maldives’ robust tourism-driven GDP bars it from accessing more affordable financing

- ‘Ras Male’ and similar projects are ineligible for climate funds because they fall under infrastructure development

- SIDS receives only about 14% of the finance that the least developed countries receive

The Maldives, a picturesque Indian Ocean archipelago known for its luxurious tourism, faces an existential threat from rising sea levels. This low-lying nation has been vocal about the disproportionate impact of climate change on its survival. On Saturday 25th May, the Maldives demanded international funding to address the severe consequences of rising sea levels, highlighting the unjust exclusion of the country from the most generous support measures available to other nations.

You can also read: Will Tax Reforms Secure the Future of Bangladesh’s Economy?

President Mohamed Muizzu, in an article for Britain’s Guardian newspaper, emphasized the disparity between the Maldives’ minimal contribution to global emissions and the severe impact it faces.

“The Maldives is liable for just 0.003 percent of global emissions, but is one of the first countries to endure the existential consequences of the climate crisis,”

– Mohamed Muizzu (Maldives president)

“The Maldives is liable for just 0.003 percent of global emissions, but is one of the first countries to endure the existential consequences of the climate crisis,” Muizzu wrote.

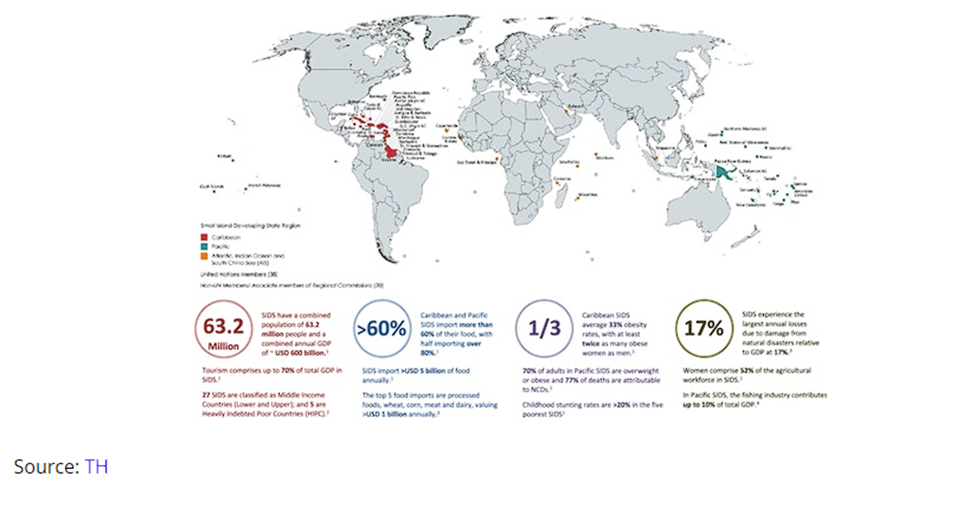

Muizzu’s remarks precede the important once-a-decade conference of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), where he will co-chair in Antigua and Barbuda, starting Monday. This gathering is critical for small island nations, many of which are renowned luxury tourism destinations now facing growing risks from rising sea levels. Despite their vulnerabilities, Muizzu highlighted that SIDS receives only about 14% of the financial support allocated to the least developed countries.

Recent Macroeconomic Trends in Maldives

In 2019, real GDP in the Maldives surged by 7.0%, driven by robust investments in tourism, commerce, and construction. However, this growth followed a period of slower expansion, with GDP increasing by 2.5% in 2012 and 2.9% in 2015, leading to macroeconomic imbalances such as twin fiscal and current account deficits. The economy suffered a significant blow in 2020, contracting by 32% due to the pandemic’s impact on tourism. Nevertheless, there was a remarkable rebound with GDP growing by 33.4% in 2020, fueled by a strong recovery in tourism.

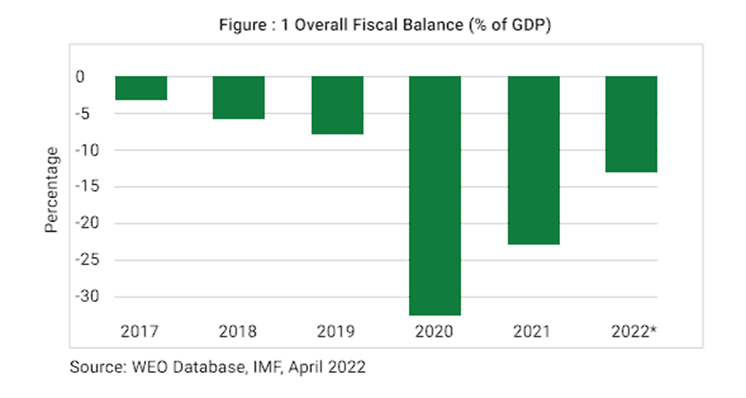

Fiscal expenditure consistently outpaced revenue even before the pandemic, resulting in widening fiscal deficits, reaching 5.1% of GDP in 2018 and 6.6% in 2019. This trend was driven by various factors including public sector wage bills, pensions, subsidies, transfers to state-owned enterprises, and large public investment projects. The pandemic-induced surge in expenditure coupled with reduced revenue led to a fiscal deficit of 27.6% of GDP in 2020, which gradually decreased to 18.1% in 2021.

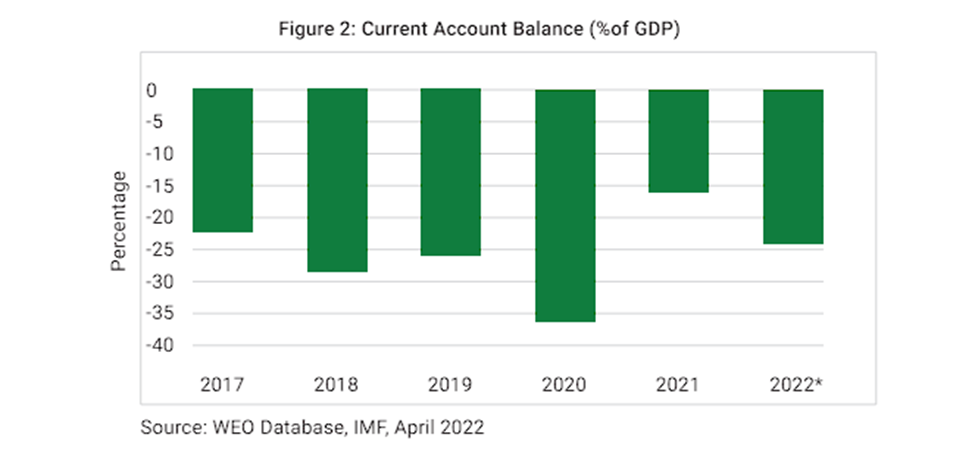

Despite lower global commodity prices and increased tourism receipts, the current account deficit remained high at 26.6% of GDP in 2019. This was primarily due to the imbalance between tourism-driven imports and fishery-driven exports, as well as higher overall imports. In 2020, tourist arrivals plummeted to a third of the 2019 level, resulting in a larger drop in exports compared to imports. Consequently, the current account deficit worsened to 35.5% of GDP in 2020 before improving to 15.6% of GDP in 2021.

About Small Island Developing States (SIDS)

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are a unique group comprising 39 states and 18 associate members of United Nations regional commissions, facing distinctive social, economic, and environmental challenges.

- SIDS are located in three geographical regions: the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and the South China Sea (AIS).

- SIDS were recognized as a special case for both environmental and developmental issues at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- These highly vulnerable developing countries suffer from low economic diversification, often relying heavily on tourism and remittances.

- They face economic volatility due to fluctuations in private income flows and raw material prices, along with significant debt stress.

- For SIDS, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)—the ocean area under their jurisdiction—is, on average, 28 times the size of their landmass.

- Thus, for many SIDS, the majority of the natural resources they have access to come from the ocean.

Economic Disparities and Funding Challenges

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Maldives boasts a higher GDP per capita than Chile, Mexico, Malaysia, or China. However, Muizzu criticized GDP as a ‘legacy metric’ that does not accurately reflect the country’s economic vulnerabilities.

The Maldives’ economy heavily relies on tourism, making it difficult to raise the estimated $500 million needed to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Although boasting a higher GDP per capita than many nations, the Maldives is categorized as an emerging economy. This classification denies the Maldives access to more affordable financing options reserved for the least developed countries. The dominance of the Maldives’ tourism industry distorts its economic indicators, hindering access to vital climate funds.

Dynamic Growth in the Maldives, still driven by tourism

Since 2023, the Maldives has seen stabilized economic growth after the severe recession between 2020 and 2022. This recession was followed by a remarkable recovery driven by a resurgence in global tourism and favorable government policies. The Maldivian economy is heavily dependent on tourism, which directly contributes 25% to the GDP and 60% when including related sectors such as food suppliers. The broader service sector accounts for 78% of GDP.

Tourism continues to be the main driver of growth, bolstered by a significant increase in Chinese tourists. The Maldives, a top destination for Chinese travelers before the pandemic, was among the first to be authorized for travel by the Chinese government in late 2022. Along with visitors from India and Russia, this influx is expected to offset the reduced tourist numbers from the European Union and the United States due to their weaker economies and competition from emerging destinations like Thailand. This growth will positively impact tourism-related sectors, including transport and retail.

Additionally, major public investments in infrastructure to support tourism will boost the economy. The Greater Malé Connectivity Project, aimed at linking Malé to the islands of Villingli, Gulhifalhu, and Thilafushi by road, is expected to be completed by the end of 2024. The expansion of Velana International Airport will also continue.

Inflation is anticipated to moderate in 2024 after two years of high levels, due to cheaper food and energy imports and a gradual reduction in public spending after the 2023 presidential and 2024 parliamentary elections. This budgetary tightening may slightly impact private consumption but will contribute to overall economic stability.

Historical Context and Ongoing Efforts

The Maldives has been sounding the alarm about climate change for decades. The first SIDS meeting in 1994 occurred five years after then-president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom warned that the nation, comprising 1,192 tiny coral islets, faced extinction if sea levels rose by a meter. Gayoom spearheaded a land reclamation project to build an artificial island two meters above sea level, which doubled the size of the congested two-square-kilometer capital island, Male.

Building on this legacy, President Muizzu, who was elected in September last year, has proposed an even more ambitious project. He unveiled plans for ‘Ras Male’, a larger man-made island featuring 30,000 apartments designed to combat rising sea levels. Unfortunately, this project has been ineligible for climate funding as it is classified as infrastructure work, a categorization Muizzu lamented.

Conclusion

The Maldives’ plea for international funding underscores the urgent need for a more equitable distribution of climate finance. As the world prepares for the upcoming SIDS conference, wealthier nations must recognize and act upon their moral responsibility to support vulnerable countries like the Maldives.