Japan is rapidly automating and using robotics to address its aging population and shrinking workforce caused by labor shortages and supply chain disruptions. Even iconic services like food trolleys on bullet trains and stocked vending machines are being impacted by the labor shortage. This crisis is changing how the government, companies, and people operate and plan for the future.

Reports estimate Japan will have a shortage of 11 million workers by 2040, as nearly 30% of the population will be over 65 by 2042. Japan has relied on female and elderly workers in the past decade, but this is no longer enough to sustain the workforce. To tackle this demographic challenge, Japan is introducing avatars, robots, and artificial intelligence into key sectors of its workforce.

Construction Industry

Japan’s construction industry has struggled for a long time to hire enough workers, despite efforts to attract more women and young people by increasing wages, providing better uniforms, and installing portable toilets for women at construction sites.

However, the number of construction workers has decreased by 30% since its peak in 1997 to 4.8 million workers, according to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Only 12% of construction workers are under 29 years old, while about 36% are over 55.

The staffing problems in the construction sector are so severe that the industry was given five years to prepare for new labor rules that will limit overtime for construction workers and truck drivers, which are now in effect this month.

Due to these labor shortages, the estimated cost of the Osaka World Expo 2025 has doubled to more than $1.6 billion, as contractors have to pay higher wages to attract workers. Some countries are scaling back their presence at the expo, fearing rising costs and delays. Japan’s major national event could be directly impacted by its labor shortages, diplomats have warned.

Supply Chain

For decades, the major Japanese confectionery company Lotte has delivered its popular bear-shaped chocolate biscuits, Koala’s March, by truck. However, due to an acute shortage of truck drivers caused by new overtime rules, Lotte will now deliver this beloved children’s snack by train.

Other companies across Japan, including automaker Toyota and e-commerce firm Rakuten, are also making preparations to address the driver shortage. This includes developing robots, self-driving vehicles, and consolidating with smaller rivals.

Japan’s approximately 4 million vending machines require many truck drivers to keep them stocked. However, the gaps between refills are increasing, even in large cities, as there are fewer drivers available. The vending machine industry is rushing to adapt, with one company, JR East Cross Station, starting to use trains in November to transport drink cans to restock some vending machines.

At its Motomachi plant in Aichi Prefecture, Toyota has introduced a fleet of ‘vehicle logistics robots’ to pick up and move cars to the loading area. Eventually, Toyota hopes to replace 22 human workers in the yard with just 10 robots.

Farming

Last summer in Miyazaki prefecture, southern Japan, a solar-powered robot duck called Raicho 1, made by Kyoto company Tmsuk, was used in the rice paddies to churn up weeds. This robot was part of a suite of drones and robots designed to sow, nurture and harvest rice crops without human labor. A high-pressure water cannon was also used to scare away wild boars and deer that now roam more freely as the human population has declined in the area.

The experiment, which ended with the October rice harvest, produced a promising result – the total number of human labor hours was reduced from 529 to 29, a 95% reduction, with only a 20% decrease in the total rice yield.

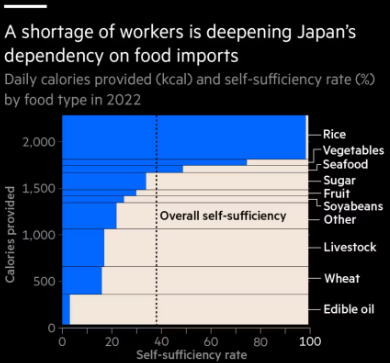

As Japan’s population has shrunk and aged, agricultural labor shortages have become severe. Government data shows Japan was only 38% self-sufficient in calorie terms in 2022, against a target of 45% by 2030 – a target that looks increasingly difficult to achieve. Over 10% of farmlands are now abandoned nationwide.

With 43% of Japanese farmers over 75 years old and the average farmer age nearly 68, Tmsuk’s CEO Yoichi Takamoto said Japan has little choice but to embrace a robot workforce in agriculture to preserve famous regional agricultural products.

Retail

Labor shortages have forced Japanese retailers and convenience stores, known as ‘combini’, to reduce hours and services. In 2020, Japan’s convenience stores were short of 172,000 workers, and the industry body forecasts a gap of 101,000 workers by 2025. As a result, only 87% of combini are now open 24 hours, compared to 92% in August 2019.

Hiring foreign students, who can work despite Japan’s tight immigration restrictions, is an option. However, some need weeks of training to meet customer expectations.

Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has warned about the shrinking labor force and overall population, stating last year: “Japan is standing on the brink of whether we can continue to function as a society.” With fewer workers, many hope artificial intelligence (AI) can fill the gap.

The head of Japan’s largest recruitment agency, Recruit Holdings, says AI will resolve Japan’s labor shortages but cautioned that its usefulness will be limited until people trust the technology more.

CEO Hisayuki Idekoba said Japan ‘needs to go all in on AI’, pointing to successes in using AI tools to attract more job candidates. However, he added that AI adoption in developed economies will be slower than expected due to deeply rooted public mistrust of letting technology into their lives.