Key Highlights:

- Public Eye, a Swiss investigative organization, has cast a glaring spotlight on Nestle’s practices by examining 115 products, 108 of which (94%) revealed that Nestle’s baby food products in several countries

- Thailand recorded the highest sugar dose at 6g per serving, trailed by Ethiopia at 5.2g, South Africa at 4g, Pakistan at 2.7g, India at 2.2g, and Bangladesh at 1.6g

- In Africa, there’s been a nearly 23% rise in the count of overweight children under the age of five since 2000

Nestle, a household name synonymous with nourishment, has found itself embroiled in a bitter dispute that juxtaposes corporate strategy against public health. The company holds a substantial position in the worldwide baby food market, accounting for roughly 20% of the market share with annual global sales reaching approximately $2.5 billion. Given the pivotal role these products play in the nutritional intake of infants and young children globally, the concern over sugar content becomes notably urgent.

You Can Also Read: Disney Parks, Top Money Maker

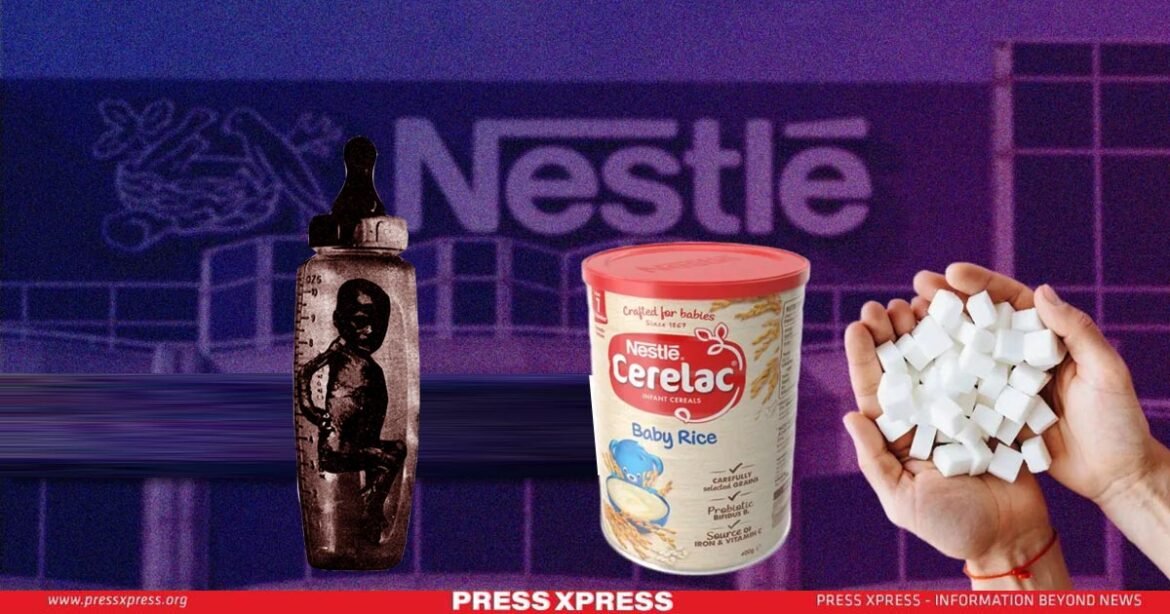

A recent expose by Public Eye, a Swiss investigative organization, has cast a glaring spotlight on the company’s practices. After examining 115 products, 108 of which (94%) revealed that Nestle’s baby food products in several countries, notably India, Africa, and Latin America, contain higher levels of sugar than those in Europe.

This revelation has sparked significant concern, particularly in low-income countries where Nestle’s popular brands like Cerelac and Nido were found to contain high levels of sucrose and honey. These ingredients are linked to obesity and diabetes—maladies that burden societies with lifelong healthcare challenges.

The controversy is not new; it echoes the historical outcry of the 1970s when Nestle was accused of undermining breastfeeding by aggressively marketing infant formula in less affluent nations. Today, the company faces renewed scrutiny as disparities in product formulations across geographies raise questions about the equity of nutritional standards.

Cerelac Packs Hidden Sugar Punches for Babies

Of particular concern is Nestle’s wheat-based product, Cerelac, tailored for 6-month-old infants. Cerelac reigns as the leading baby cereal brand globally, boasting sales surpassing $1 billion (€940 million) in 2022.

According to the study, all 15 Cerelac baby food variants in India contain an average of almost 3 g of sugar per serving. On the flip side, Thailand recorded the highest sugar dose at 6g per serving, trailed by Ethiopia at 5.2g, South Africa at 4g, Pakistan at 2.7g, and Bangladesh at 1.6g.

While sugar content was properly labeled on packaging in India, the report uncovered a significant oversight in the Philippines, where 5 out of 8 samples contained a high 7.3 grams of sugar per serving, with no mention on the packaging.

However, Nestle India has defended its actions by pointing out reductions in sugar content of up to 30%, and the debate surrounding this issue continues to rage on.

Notably, Nestle’s sales of Cerelac products in India reached over ₹20,000 Crore in 2022 and milk products and nutrition portfolio, spanning dairy whitener, condensed milk, yogurt, maternal and infant formula, baby foods, and healthcare nutrition, reported sales of ₹6,815.73 crore.

72% of Nido Toddler Milk Laden with Added Sugar

Nido powdered milk brand has surpassed $1 billion in global sales, targeting children aged 1 to 3, according to data from Euromonitor disclosed by Public Eye. Analysis by the latter indicates that out of the 29 tested Nido products available in certain low- and middle-income countries, 21 (72%) contain added sugar.

The amount of added sugar varies across markets. For instance, no added sugar was found in Nido powdered milk for 1-year-olds in Brazil and the Philippines. However, a product sold in Panama was found to contain as much as 5.3g per serving. Similarly, in Nicaragua, a Nido powdered milk product contained 4.7g per serving, while in Mexico, the level was 1.8g.

What’s the Limit on Sugar for Infants?

In 2015, the WHO advised countries to restrict the consumption of free sugars to 10% of total energy intake for both children and adults. Moreover, it proposed lowering this threshold to 5% or 25g per day. This guidance pertains to added sugars in processed foods, excluding naturally occurring sugars in fruits and milk.

Children under 4 are not assigned a specific sugar limit but are encouraged to steer clear of sugary beverages and foods with added sugar. Emphasizing nutritious choices assists children in upholding a well-rounded diet and promotes their general well-being.

An overabundance of sugar in infant foods presents a substantial risk to a baby’s well-being, potentially causing unhealthy weight gain, heightening the likelihood of Type 2 diabetes, and adversely affecting dental health.

In Africa, there’s been a nearly 23% rise in the count of overweight children under the age of five since 2000. On a global scale, the WHO noted that over one billion individuals are grappling with obesity.

“Excess sugar uptake can result in health complications like obesity, dental decay, and a higher propensity to chronic illnesses later in life. High sugar consumption from baby food significantly contributes to speeded weight gain and obesity in babies and toddlers. Early childhood obesity is serious, as it can pave the way for obesity-related issues in the future, such as type 2 diabetes, heart issues, and high blood pressure.”

– Dr Rajadeepa Chatterjee, Apollo Hospitals

A Costly Cover-Up: Nestle’s Baby Formula Scandal

In the 1970s, the company targeted marketing efforts toward developing nations in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Saleswomen, disguised as nurses, were dispatched to persuade mothers that Nestle’s formula was superior to their breast milk.

Facing financial constraints, many women resorted to diluting the costly formula with often unsanitary water, further compromising its nutritional value. This led to the tragic deaths of millions of infants, while many suffered from malnutrition, profoundly affecting the health and longevity of populations in the developing world.

According to a report in The New York Times, the income of a Jamaican family was reported to be as low as an average of $7 per week. Consequently, the mother had to resort to diluting the water with up to 3 times the recommended amount to provide sustenance for her two children. The company neglected to educate consumers on proper usage and even bribed healthcare professionals to support its false claims.

The Infant Formula Action Coalition initiated a boycott against Nestle in the United States, which subsequently gained momentum in France, Finland, Norway, and numerous other nations. Although the boycott was temporarily halted in 1984, it reemerged in the late 1980s as Ireland, Australia, Mexico, Sweden, and the United Kingdom joined in.

In conclusion, breast milk stands as the optimal and innate nourishment for every newborn, with the World Health Organization advocating for exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months of age. Nestlé should strictly follow the guidelines set forth by the WHO Code, refraining from promoting products for infants under 6 months. With the rising global obesity crisis, especially among children, raises the question: Is it feasible, and morally right, for a corporation’s profit-driven motives to coincide with safeguarding the most susceptible?