Key Highlights:

- Under Akbar’s reign, the tradition of celebrating Pohela Boishakh began.

- At the heart of this centuries-old jubilation lies the ‘Boishakhi Mela’ (Boishakhi Fair), spanning various locales across the nation and lasting for at least a week.

- On the eve of Bengali New Year, Bengalis flock to the Kalighat temple to offer their prayers.

Pohela Boishakh, recognized as the Bengali New Year, heralds the beginning of the Bengali calendar, commonly observed on April 14 in Bangladesh and/or April 15 in certain regions of India according to the Gregorian calendar. Bengalis residing abroad have creatively embraced their cultural customs, endeavoring to evoke a feeling of home in distant lands.

Festivities include lively fairs in urban areas, where people exchange greetings with the traditional phrase “Shubho Nobobarsho,” meaning Happy New Year. In Bangladesh, the iconic Mangal Shobhajatra procession adds to the jubilant atmosphere.

You Can Also Read: UNIQUE CELEBRATION OF NEW YEAR IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

Rooted in the customs of Old Dhaka’s Muslim community during the Mughal era, as well as Akbar’s tax reforms, Pohela Boishakh carries historical significance.

In recognition of its cultural importance, UNESCO designated the festivity organized by the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka, as a cultural heritage of humanity in 2016.

As we delve deeper into its essence, one can’t help but wonder: How does this age-old tradition continue to evolve and resonate across generations and continents?

The Festive Legacy of Mughal Tax Reforms

During the Mughal era, agricultural taxes were levied based on the Hijri calendar, creating challenges for farmers due to misalignment with harvest seasons. Emperor Akbar recognized this issue and initiated a reform to synchronize tax collection with agricultural cycles.

To achieve this, Fatehullah Shirazi, a respected scholar and astronomer, devised the Bengali year by combining elements from the Hijri lunar and Hindu solar calendars. Inaugurated on 10/11 March 1584, retroactively dated from Akbar’s ascension in 1556, this calendar became known as the Fasli San, or agricultural year, and later as the Bengali year or Bonggabdo.

Under Akbar’s reign, the tradition of celebrating Pohela Boishakh began. Landowners would settle all debts on the last day of Choitro, followed by festivities on the first day of the new year. This included treating tenants to sweets and community fairs. Pohela Boishakh evolved into a day of joyous gatherings, with a key ritual being the opening of new account books, known as “Halkhata.”

This tradition, focused on financial matters, extended across villages, towns, and cities, where traders closed old accounts and welcomed customers with sweets, symbolizing the renewal of business relationships. Even today, particularly among jewellers, this tradition persists, reflecting its enduring cultural significance.

The Magic of Pohela Boishakh in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the festivities kick off early in the morning as thousands converge beneath the banyan tree at Ramna Park, known as the Ramna Batamul, for the annual cultural extravaganza. Commencing with the iconic song of Rabindranath Tagore, “Esho hei Boishakh, esho, esho,” the programs often unfold with a medley of cultural performances.

Homes are cleaned and adorned with traditional “Alpana” designs, an age-old custom.

Individuals don vibrant traditional attire mainly combination of white and red, pay visits to loved ones, and relish in a spread of traditional delicacies such as Panta Bhat (Watered rice), Ilish Bhaja (Fried Hilsa Fish), Dried fish, and an assortment of bhartas (Pastes), among other culinary delights.

At the heart of this centuries-old jubilation lies the ‘Boishakhi Mela’ (Boishakhi Fair), spanning various locales across the nation and lasting for at least a week. While previously held on Chaitra Sankranti, marking the final day of the Bengali calendar, the fair has evolved from a month-long affair into its current form.

The fair showcases an array of traditional products, agricultural produce, handicrafts, pottery, wooden furniture, toys, cosmetics, and an assortment of delectable foods and sweets. It is accompanied by traditional events such as Circus performances, Puppet shows, Jatra, Palagaan, Kabigan and rural sports like Nouka Baich (Boat race), Bull race, and Kite flying, commemorating this vibrant occasion.

Pohela Boishakh in West Bengal

On the eve of Bengali New Year, Bengalis flock to the Kalighat temple to offer their prayers. Places of worship like Dakshineswar and Belur also experience a surge in devotees. Families engage in thorough cleaning and adornment of their homes in anticipation of the occasion.

For many, the day commences with a sacred dip in the Ganges, ideally just before dawn. Traditional attire such as kurtas and pajamas for men and sarees for women adorn the celebrants. Most clothing stores launch their “Chaitra Sale” or end-of-year sale a month prior to Pohela Boishakh.

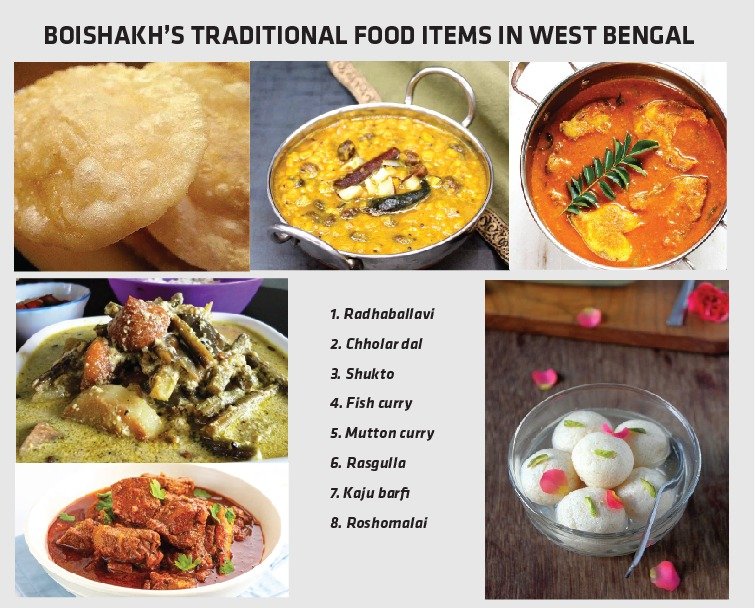

Partaking in quintessential Bengali cuisine, including dishes like radhaballavi, chholar dal, shukto, fish, and mutton curry, is customary. Sweet delicacies like rasgulla, kaju barfi, and roshomalai grace household tables. Cultural festivities dot the landscape of Bengal and beyond. Musical performances featuring Rabindrasangeet, Najrulgeeti, folk songs, and dances are integral to these events. Streets and parks come alive with vibrant decorations, illuminated by colorful lights, while megaphones serenade localities with Bengali melodies.

Boishakh Around the World

In the heart of New York City, the vibrant Bangladeshi community gathers at Jackson Heights, Queens. Colorful processions wind through the streets, accompanied by traditional music and dance. Food stalls offer mouthwatering delicacies like panta bhat (fermented rice), ilish bhapa (hilsa fish cooked in mustard paste), and mishti (sweets).

London’s Brick Lane transforms into a mini Dhaka during Pohela Boishakh. The curry houses lining the street serve bhapa pitha (steamed rice cakes), chingri malai curry (prawn curry), and roshogolla (spongy syrup-soaked sweets). The iconic Altab Ali Park hosts cultural performances, where expatriates sway to Rabindra Sangeet and folk tunes.

Toronto’s Gerrard Street East becomes a canvas of alpona designs during Pohela Boishakh. Families gather for picnics, clad in traditional attire. The aroma of biryani wafts through the air, and children participate in art competitions. The Canadian-Bengali diaspora cherishes this day as a bridge between their heritage and their adopted homeland.

In Sydney, the Bangladeshi community congregates at Parramatta Park. Colorful masks, banners, and floats depict themes of resilience, unity, and hope. The Australian sun bathes the revelers as they dance to the beats of dhak (traditional drum) and immerse themselves in the spirit of renewal.

In Tokyo, the Bengali expatriates gather at Yoyogi Park. Amid cherry blossoms, they share stories of their homeland, recite Tagore’s poetry, and indulge in panta bhat. The fusion of Japanese and Bengali culture creates a unique celebration, where hanami (flower viewing) meets Boishakh.

Whether in bustling cities or quiet suburbs, Bengalis and their friends come together to celebrate renewal, unity, and the promise of a new year. As we welcome another glorious Boishakh, let us carry forth the spirit of unity, diversity, and harmony that defines this enchanting festival, ensuring that its legacy continues to shine brightly for generations to come. Shubho Nobobarsho!