Key Highlights:

- More than four billion people expected to vote this year, which makes deepfakes a matter of serious concern

- Deepfakes leading to more confusion between truth and lies and eroding the confidence in democratic institutions

- According to the Sumsub report, the Asia Pacific region experienced a 1,530% surge in deepfake occurrences from 2022 to 2023

- Tech giants admit that detection and watermarking technologies for identifying deepfakes haven’t kept pace with AI-generated content’s rapid growth and enhancement

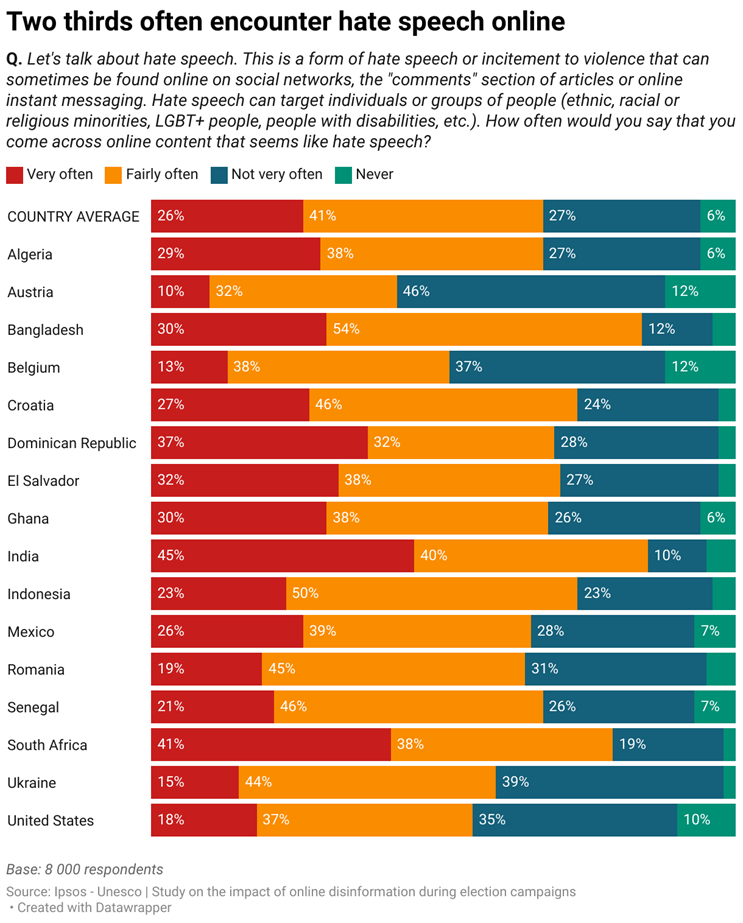

Online hate speech, misinformation, and lies are not new, but the scale of the ‘misinformation pandemic’ created by AI and AI-generated bots, or automated social media accounts now worsen. AI-driven large language model now made it easier to run convincing propaganda campaigns through bots. A study by PNAS Nexus says that generative AI will be used more by disinformation campaigns, trolls, and other “bad actors” to create election lies in 2024.

You Can Also Read: DEEPFAKES IN ELECTIONS: A THREAT TO DEMOCRACY OR A MORAL PANIC?

According to a Sumsub report, the number of deepfakes worldwide rose by 10 times from 2022 to 2023. In Asia Pacific countries alone, deepfakes surged by 1,530% during the same period. Online media, including social platforms and digital advertising, saw the biggest rise in identity fraud rate at 274% between 2021 and 2023.

Deepfakes of politicians are becoming increasingly common, especially with 2024 set up to be the biggest global election year in history. More than 50 countries and four billion people are voting this year, which makes deepfakes a matter of serious concern and can lead to more confusion between truth and lies and erode confidence in democratic institutions.

On January 7, 2024, the day of the 12th Jatiya Sangshad election in Bangladesh, a fake video was seen to be circulating on social media, in which Abdullah Nahid Nigar, an independent candidate for the Gaibandha-1 constituency, announced that she has withdrawn from the election. However, the video was fake and created with the help of AI thus creating confusion among the constituency’s voters.

The day after Pakistan’s national election, jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan claimed victory- via a video generated using artificial intelligence (AI).

Asia is not ready to tackle deepfakes in elections in terms of regulation, technology, and education, said Simon Chesterman, senior director of AI Singapore.

In its 2024 Global Threat Report, cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike reported that with the number of elections scheduled this year, nation-state actors including China, Russia, and Iran are highly likely to conduct misinformation or disinformation campaigns to sow disruption.

The Role of AI in Information Manipulation

Several studies on the impact of disinformation in previous elections have shown how bots at large can spread disinformation or fake propaganda, thereby manipulating public trust and mandate. Bots are programs that repeat messages created by humans or other programs. But now, bots can also use large language models (LLMs) to create text that sounds human. This makes them more dangerous and harder to detect. “It’s not just generative AI, it’s generative AI plus bots,” says Kathleen Carley, a computational social scientist at Carnegie Mellon University.

Political candidates use AI to reach voters, create messages, and speak more languages. For example, India’s Prime Minister Modi uses AI to talk in Hindi and Tamil. But AI can also be used for mischief, such as making memes, songs, and deepfakes of politicians.

AI can also affect how voters get information. Online chatbots powered by generative AI can provide helpful or harmful information, depending on the source and the intention. Some chatbots can mislead voters about voting sites, candidates’ views, and reliable sources. This can increase election misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories.

AI can also make it easier and cheaper to create and spread deepfakes, which are fake images and videos. Anyone with some coding skills and software can make a deepfake in minutes. Deepfakes can damage the reputation and mental health of politicians, or create pornographic images of them. This can harm democracy and discourage people from running for office.

Deepfakes can also worsen racism and prejudice in society. They can target or misrepresent groups or individuals based on their identity or beliefs. This can increase social conflicts and challenges for democracy defenders, such as civil society, peacebuilders, technology companies, and governments.

Social Media Shapes Political Campaigns in Southeast Asia

Social media is a key tool for political campaigns in Southeast Asia. Candidates and parties use platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok to connect with voters, spread their message, and mobilize support.

In Cambodia, Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has ruled since 1985, has used social media to reach the public. He deleted his Facebook account with more than 14 million followers (many fake) after Meta threatened to suspend it for inciting violence. He then switched to Telegram and TikTok and also promoted a TV show about his life on YouTube.

In Thailand, the Move Forward Party (MFP) won 151 out of 500 seats thanks to its leader Pita Limjaroenrat’s social media appeal. He has 2.6 million followers on Instagram, where he posts friendly photos of his family.

In Malaysia, parties have used social media to boost their narratives. Last year, the conservative Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) won most seats with its hate speech campaign on TikTok. PAS President Abdul Hadi Awang is also on Facebook, but the party focused on TikTok, which has more than 14.4 million users in Malaysia.

Myanmar’s NUG leverages social media for civil war communication, reaching a broad audience and amplifying local voices post-2021 coup. Despite the praise, it faces criticism over potential propaganda and misinformation.

Southeast Asian politicians and parties have learned to use social media effectively to present themselves as relatable, to disseminate their messages, and to mobilize their supporters. They have also learned to target their messages to specific segments of voters, based on their preferences and interests. This can increase their political appeal, but it can also create online echo chambers and polarize society, as seen in the elections in Indonesia in 2019 and Malaysia in 2022.

Social media also poses challenges to political integrity and democracy. It also opens the door to foreign interference, which can undermine the democratic process.

To address these challenges, three actions are needed. First, the public needs to be aware of the dangers of misinformation on social media, and how to verify the information they see online. Second, tech giants need to be more active in removing false and harmful content and making it easier for users to report such content. Third, social media companies need to be more transparent about their moderation policies so that users can trust them and hold them accountable.

Big Tech Scales Back Protections

Amid the 2024 election year, many people around the world are worried about the spread of disinformation on social media platforms, according to a UNESCO survey. However, the efforts of Meta, YouTube, and X (formerly Twitter) to curb harmful content have been inconsistent and insufficient, a report by Free Press, an advocacy group, said. These platforms have reduced or restructured their teams that monitor and remove dangerous or false information and have introduced new features, such as one-way broadcasts, that are hard to oversee.

Free Press’s senior counsel, Nora Benavidez, warned that these platforms have “little bandwidth, very little accountability in writing and billions of people around the world turning to them for information” – a risky situation for democracy.

Meanwhile, newer platforms such as TikTok, are expected to play a bigger role in shaping political discourse. Substack, a newsletter service that refused to ban Nazi symbols and extremist language from its platform, declared that it wants the 2024 elections to be “the Substack Election”.

Meta, the owner of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, claimed in a blog post in November 2023 that it was “in a strong position to protect the integrity of elections on our platforms”. However, its oversight board criticized its use of automated tools and its handling of two videos related to the Israel-Hamas conflict in December 2023.

YouTube said that its “elections-focused teams have been working nonstop to make sure we have the right policies and systems in place”. However, the platform also announced that it would stop removing false claims about voter fraud.

X saw a surge of toxic content on its platform. Alexandra Popken, who was in charge of trust and safety operations for X, quit her job and said that many social media companies rely too much on unreliable A.I. tools for content moderation, and leave a few human workers to deal with the constant crises. “Election integrity is such a behemoth effort that you really need a proactive strategy, a lot of people and brains and war rooms,” she added.