Tobacco farming once heralded as a beacon for financial prosperity, is now faced with critical scrutiny due to its adverse impact on the environmental and health landscape of the nation. Driven by the allure of quick profits, alongside a backdrop of limited awareness and rural impoverishment, it’s hardly shocking that this agricultural path continues to be trodden, despite the stark repercussions.

The Roots of Tobacco in Bangladesh

Tracing back to the 1960s, the landscape of this country’s farming began to see a significant shift with the introduction of large-scale cultivation of this crop. This transformation was further accelerated post-liberation in 1971. The legacy of tobacco farming is deeply rooted in its significant economic and social ramifications, especially after independence when the Teesta region’s rich soils became synonymous with tobacco cultivation.

This shift was notably driven by the initiatives of the British American Tobacco Company, positioning this country as a major global tobacco producer. The sector has not only contributed to the country’s economy but also to a complex socio-financial fabric, intertwining farmers’ livelihoods with the cultivation of this crop.

You can also read: Higher Interest Rates Tempt Depositors Back to Banks!

Despite the challenges and the ecological impacts associated with cultivation of this crop, such as clearing of forests, deterioration of soil, and agrochemical contamination, this crop remains a critical agricultural commodity. Efforts to control production of this crop face barriers due to the financial implications for farmers, compounded by political and commercial interests. The continuation of growing this crop, heavily influenced by contracts with multinational this crop companies, underscores the ongoing debate between financial advantages and ecological balance

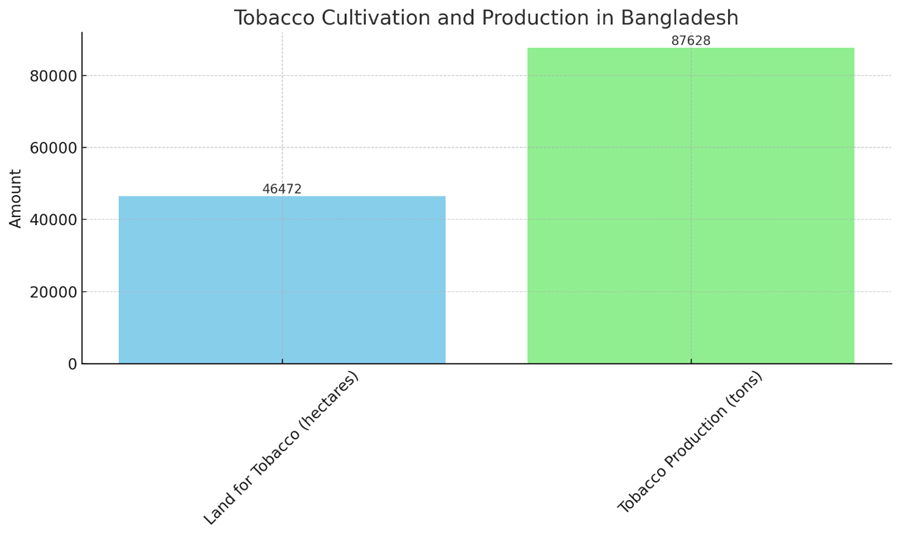

The Scenario of Tobacco Cultivation

Due to the inevitable soil degradation caused by tobacco cultivation, it tends to relocate from one area to another over decades. A study by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) reveals that the British American Tobacco Company initiated tobacco cultivation in Bangladesh during the 1970s.

Initially, the Rangpur region became a tobacco hotspot due to its access to water from the Teesta River, ample wood for tobacco curing, and fertile land.

However, as the fertility of the Rangpur tobacco hub declined, cultivation shifted to the Kushtia region.

Despite Kushtia remaining the primary tobacco hub, followed by Lalmonirhat and Nilphamari, since 2000, a shortage of firewood has prompted a shift in cultivation to the Chittagong Hill Tract districts along the Matamuhuri River.

The Environmental Toll

Tobacco farming imposes a significant ecological and agricultural toll in this country, extending far beyond the fields where it is cultivated. This agricultural practice contributes to clearing of forests, leading to a reduction in biological diversity and increased the release of harmful gases.

Soil erosion, a direct consequence of clearing land for this crop, compromises soil well-being and farming output. The intensive use of agrochemicals in growing this crop contaminates both soil and water bodies, posing serious well-being concerns to both farmers and surrounding communities.

Moreover, the prioritization of this crop over food crops threatens food stability in a country where arable land is scarce and precious. This shift not only affects the environment but also has broader implications for societal well-being and financial resilience. The challenge lies in balancing the immediate financial advantages derived from cultivation of this crop against the long-term sustainability of this country’s agricultural and natural ecosystems.

A Cycle of Dependency

The profitability of cultivation of this crop obscures a grim reality of dependency, well-being hazards, and ecological degradation. This dependency cycle is sustained by the crop industry’s structure, where farmers are often ensnared in contracts that bind them to growing this crop due to financial constraints and indebtedness.

Additionally, the well-being concerns associated with this form of farming, notably green this crop sickness (GTS), underscore the dire occupational hazards faced by these workers. GTS, a condition resulting from nicotine absorption through the skin from handling wet this crop leaves, manifests through symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, and dizziness, further exacerbating the occupational risks for farmers with limited access to protective gear and well-beingcare.

The use of agrochemicals in cultivation of this crop compounds these challenges, posing dire ecological and well-being consequences. As a monocrop, this crop requires significant chemical inputs, including a range of pesticides and fertilizers, which not only degrade soil quality and biological diversity but also pose severe well-being concerns to those exposed to them.

Studies have highlighted the neurological and psychological impacts of pesticide exposure among this crop farmers, including increased risks of conditions like depression and anxiety. Moreover, these chemicals contribute to pollution in aquatic environments, affecting both local ecosystems and community well-being.

Yet, there are glimmers of hope and alternatives. For instance, in Brazil, a shift towards eco-friendly farming practices among former this crop farmers is demonstrating the viability and benefits of moving away from growing this crop.

These farmers have transitioned to organic farming, growing a diverse array of food crops without the use of harmful pesticides and fertilizers, thereby improving soil well-being, enhancing biological diversity, and ensuring food stability. Their experiences underscore the potential for agricultural practices that prioritize ecological balance and well-being over the monoculture of this crop.

This juxtaposition of the entrenched challenges of cultivation of this crop against the backdrop of successful transitions to eco-friendly farming practices highlights a critical pathway for change. It emphasizes the need for comprehensive support mechanisms, including education, access to credit, and governmental strategies that encourage and facilitate a move towards ecologically friendly and well-being-conscious agricultural practices.

The Need for a Transition

Promoting eco-friendly alternatives to cultivation of this crop is imperative for this country to mitigate the adverse impacts of clearing of forests, deterioration of soil, and chemical contamination in farming. This involves fostering the adoption of crops that are not only ecologically friendly but also financially viable for farmers. By encouraging diversification in farming, this country can reduce its dependency on this crop, thereby enhancing food stability, preserving biological diversity, and improving the livelihoods of rural communities.

Government policies and interventions play a crucial role in this transition. Incentives for eco-friendly farming practices, along with educational programs aimed at increasing awareness about the ecological and well-being concerns associated with growing this crop, are essential. Furthermore, access to credit and markets for alternative crops must be improved to ensure that farmers have the financial and logistical support necessary to make the shift.

International experiences, such as the success stories from Brazil where this crop farmers have successfully transitioned to eco-friendly crops, offer valuable lessons for this country. These examples underscore the importance of comprehensive support systems, including technical assistance, access to eco-friendly farming technologies, and market development for alternative crops.

The path towards a greener future also involves collaboration between the government, NGOs, the private sector, and the international community. Joint efforts can provide the resources, knowledge, and infrastructure needed to support eco-friendly agricultural practices and ensure that ecological conservation is integrated into the national development agenda.