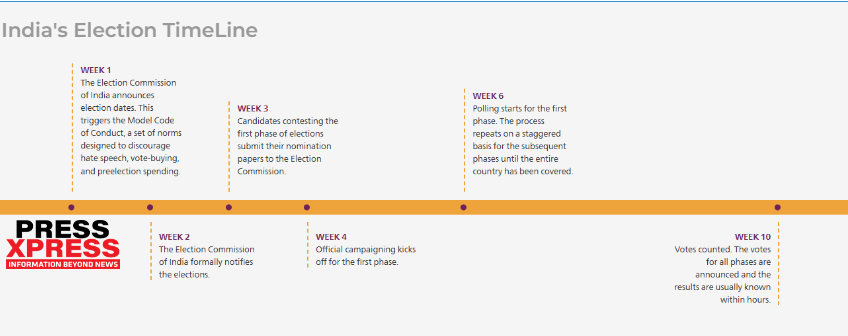

India is gearing up for an electoral feat of unprecedented scale, set to take place in April-May. To effectively conduct the world’s biggest electoral process, voting machines are being delivered to the most secluded regions of the western desert via camelback, while sophisticated control rooms are being established to thwart the spread of deceptive deep-fakes and propaganda.

You can also read: From Fragile 5 To Top 5: How BJP’s Rule Brought Fortune to India

With over 960 million registered voters, India’s electoral rules require a polling station within 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) of every habitation, resulting in over one million polling locations nationwide. In a mammoth electoral exercise with 2,400 political parties that may contest in the polls, India’s current Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to clinch a historic third term in office.

India’s Election Commission is expected to announce the polls schedule this week. Two key political parties –BJP and Congress–already published their heavyweight candidates’ list leaving no stone unturned to lead the race.

The election commission has set up hundreds of control rooms to spot and control deceptive deepfakes and propaganda content on social media centering the elections.

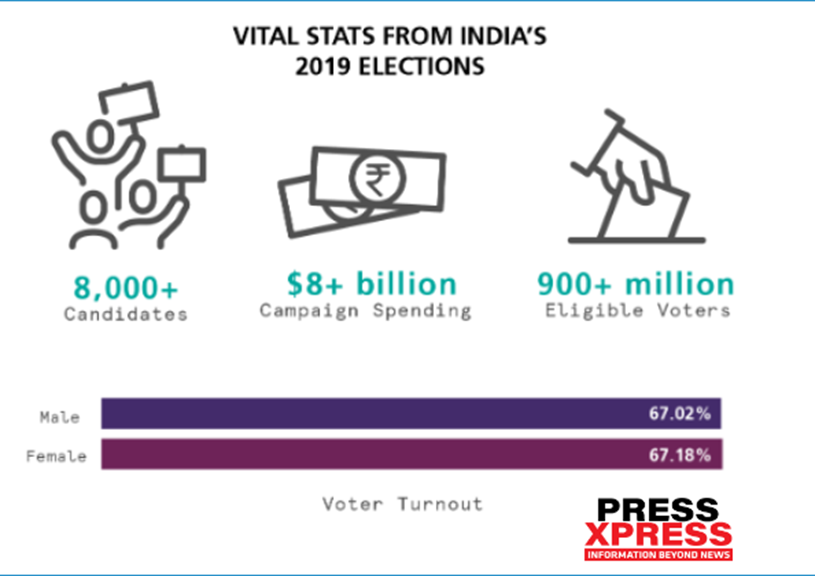

India’s elections are the world’s costliest, outspending the US. In 2019, $8.7 billion was spent courting over 900 million voters. That year, 8,054 candidates from 673 parties vied for MP seats. Nearly 615 million people—67.4 percent of Indians—voted in 2019: this was the highest voter turnout on record.

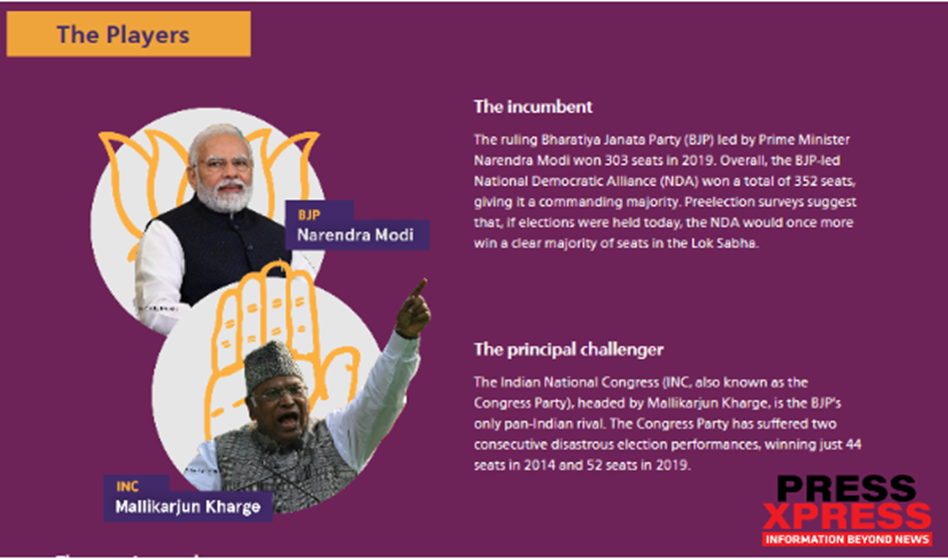

Meanwhile, according to recent opinion polls, The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is projected to win a decisive majority in the upcoming elections.

The “Mood of the Nation Poll” by India Today indicates Modi’s enduring popularity as a leader who has spurred economic growth and bolstered international relations. The survey suggests that the BJP and its allies are poised to secure 335 of the 543 parliamentary seats.

Alliance Politics

One of the distinctive features of India’s political scenario is the prevalence and importance of coalition politics, where no single party can secure a majority on its own and has to rely on the support of other parties to form a government. This phenomenon reflects the diversity and fragmentation of the Indian electorate, as well as the rise of regional parties that cater to the specific demands and aspirations of different states and communities.

The BJP and the Congress, despite being the largest and most dominant parties, have to contend with the challenge of forging and maintaining alliances with various regional and smaller parties, some of which have their agendas and ambitions.

The BJP-led NDA, which came to power in 2014 with a historic majority, has seen some of its allies deserting or distancing themselves from the coalition, due to ideological differences, policy disputes, or electoral calculations.

For instance, the Shiv Sena, a Hindu nationalist party based in Maharashtra, broke away from the NDA in 2019 and joined hands with the Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) to form a state government. Similarly, the Telugu Desam Party (TDP), a regional party from Andhra Pradesh, quit the NDA in 2018 over the issue of granting special status to the state.

The Congress-led INDIA alliance, which was formed in 2023 as a united front against the BJP with 26 parties, has also faced its share of troubles and tensions, owing to the diversity and complexity of its constituents. The alliance comprises parties with different ideologies, backgrounds, and agendas, some of which are rivals or competitors in their respective states.

For example, the Trinamool Congress (TMC), a regional party that rules West Bengal, and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI-M), a left-wing party that has a strong base in the state, are part of the INDIA alliance at the national level but are bitter opponents at the state level.

Five Issues To Watch

Five key issues are worth watching centering the elections. These include the waning predictive power of state elections, the challenge of opposition, backward castes, competitive welfarism, and foreign policy as a mass issue.

Limits Of State Election Results

Recent state assembly elections offer limited foresight into the general elections. While the BJP’s success is noteworthy, it doesn’t necessarily forecast voter behavior in the upcoming national elections.

Historically, a clear link existed between state and national election outcomes. Political scientist Nirmala Ravishankar observed that state ruling party’ candidates performed well in national elections held early in their term. However, this pattern has shifted lately.

For instance, despite the Congress Party’s victory in the 2018 Chhattisgarh assembly elections and its strong performance against the BJP in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, these successes didn’t translate into parliamentary wins. The BJP overtook Congress in these states during the Lok Sabha elections that followed shortly after. Similarly, the TRS’s landslide victory in Telangana’s state elections didn’t carry over to the 2019 national elections.

Yet, with Prime Minister Modi’s significant popularity, the 2024 elections might see a resurgence of this correlation, as voters may align with the BJP to support Modi’s leadership.

Coordinated Opposition

In the 2014 and 2019 elections, the BJP capitalized on a divided opposition to secure a majority in Parliament. The opposition’s split vote, due to multiple parties vying against each other and the BJP, led to their defeat under the first-past-the-post system.

Learning from past losses, over two dozen opposition parties formed the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA). This diverse group, including the Congress Party and regional parties, aims to challenge the BJP but faces significant hurdles:

- Unified Platform: The INDIA alliance needs a cohesive agenda beyond opposing the BJP, which garnered 45% of the vote in 2019, leaving a majority of voters unrepresented. They must present a compelling governance alternative.

- Leadership: The INDIA bloc lacks the advantage of the BJP’s charismatic Modi type leadership. To compete, they need a figure who can effectively counter Modi’s influence but this is unlikely.

- Seat-sharing: The alliance has yet to finalize a seat-sharing strategy. Parties must sacrifice individual ambitions for the greater good, a challenging task given historical rivalries.

Despite forming a coalition, as seen in Uttar Pradesh in 2019, the opposition’s combined vote share didn’t translate into seats due to a lack of unity in action. The INDIA alliance must bridge this gap to succeed.

Backward Castes Factor

The OBC Factor in Indian Politics: The political landscape in India has been significantly influenced by the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), who form the largest voter bloc. The BJP’s rise under Modi’s leadership is attributed to its success in drawing OBCs away from the Congress and regional Mandal parties. These parties had previously thrived by securing the OBC vote, but Modi’s BJP made considerable gains, especially among the lower OBCs or Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs), who felt left out of the Mandal benefits.

In 2014, the BJP won 30% of the OBC vote and 43% of the EBC vote, which increased to 41% and 48%, respectively, in 2019. This shift caused a decline in the backward vote share for the Congress and regional parties. In response, Mandal parties, led by Bihar’s Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, sought to recalibrate the political narrative through a comprehensive caste census, revealing OBCs as 63% of Bihar’s population, sparking demands for proportional job reservations.

The BJP faces challenges, particularly regarding the Rohini Commission’s recommendations on OBC subcategorization, which could redistribute reservations among various OBC communities. The commission’s report remains unpublished, and its implementation could create divisions within the OBCs and discontent among the BJP’s upper-caste base, concerned about the expansion of affirmative action.

Welfare Schemes

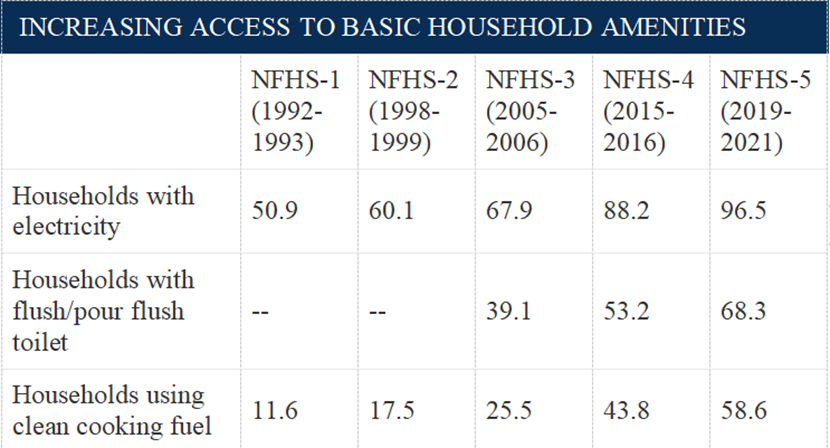

The 2024 elections are being influenced by welfare schemes and their effect on voter behavior. Arvind Subramanian, the former chief economic adviser, highlighted the Modi government’s “new welfarism,” which has significantly increased the distribution of essential goods like gas cylinders, toilets, bank accounts, and electricity since 2014. This is supported by the National Family Health Survey data, showing a marked increase in household goods access.

The government’s direct cash transfers have also seen a remarkable rise. From transferring 73.7 billion rupees ($1.2 billion) to 108 million beneficiaries in 2013–2014, the amount soared to 2.4 trillion rupees ($34 billion) for over 700 million beneficiaries in 2019–2020, with an additional 1.4 trillion rupees ($20 billion) in in-kind benefits.

While the BJP’s 2019 election victory is often attributed to nationalism, economic factors played a significant role. The government’s cash transfer scheme of 6,000 rupees ($86) to farming households likely influenced voter support, as evidenced by surveys showing beneficiaries of government schemes tended to favor the BJP.

Political parties have been promising substantial welfare benefits to win votes. The BJP, for example, offered 150,000 rupees ($1,800) to every girl child in Mizoram and 12,000 rupees ($144) annually to married women in Chhattisgarh. The BRS in Telangana and the Congress Party in Rajasthan made similar promises.

The opposition aims to match the BJP’s welfare initiatives, while the Modi government has extended a scheme providing free food grains to 800 million citizens for five more years. Despite no guaranteed electoral success, the BJP is expected to continue innovating its welfare strategies in response to the opposition’s tactics.

Foreign Policy

India’s 2024 elections are influenced by its growing global influence, blurring the lines between elite and mass concerns. Prime Minister Modi has leveraged national security incidents, like the 2019 Pulwama attack, to foster nationalism and strengthen his electoral appeal. While past security crises haven’t clearly swayed elections, the BJP’s success in 2019 suggests a shift.

Modi’s tenure is perceived to have raised India’s international stature, a sentiment amplified by the government’s promotion of its G20 presidency. This perception aligns with India’s aspiration to transition from a balancing to a leading global power.

The opposition faces challenges critiquing the government’s foreign policy without appearing unpatriotic. Their critiques often shifted, as seen during the G20 leaders’ declaration negotiations, where initial criticism gave way to claims of diluted consensus due to government concessions. This dynamic adds another layer to the electoral landscape as India positions itself on the world stage.