For centuries after centuries, people have been talking about hidden cities inside the vast wilderness of the Amazon forest. During the last 600 years, many Spanish explorers went in search of El Dorado, a mythical city made of gold, and some of them got lost for good and never came back.

Now it seems that the myth of lost cities inside the deep forest of the Amazon. The Amazon rainforest, covering much of northwestern Brazil and extending into Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and other South American countries, is the world’s largest tropical rainforest, famed for its biodiversity.

You can also read: Struggling Economies See Light at the End of the Tunnel with Global Debt Surge

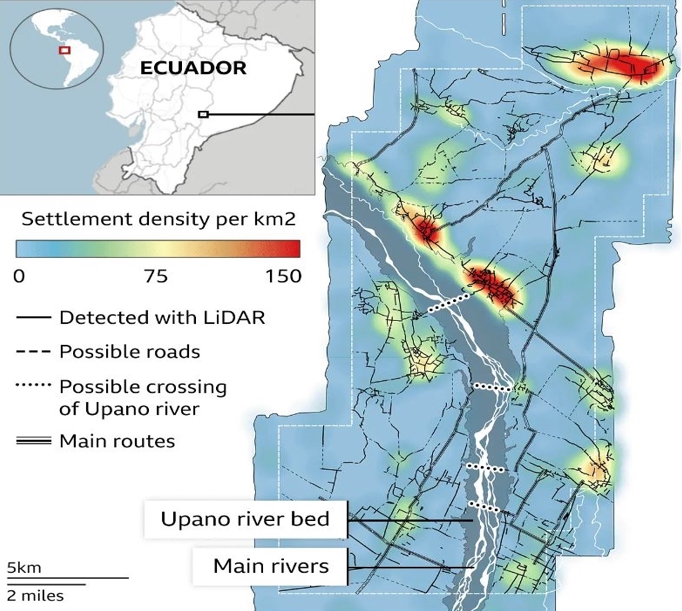

It is not imaginary as archaeologists have discovered an extensive network of cities deep inside the rainforest, revealing a 2,500-year-old lost civilization of farmers. The vast site, with wide streets and long, straight roads, plazas, and clusters of monumental platforms covering more than 1,000 square kilometers (385 square miles), was found in the jungle at the Upano valley on the eastern foothills of the Andes mountain range in Ecuador, according to a study published in the journal Science on January 11.

The discovery is the result of more than two decades of investigation by a group of archaeologists from France, Germany, Ecuador, and Puerto Rico, leading to the discovery of the earliest and largest urban network of built and dug features in the Amazon.

The French-led team of researchers used a remote sensing method called light detection and ranging (LIDAR), throwing laser light from above to detect structures below the thick tree canopies of the jungle, uncovering 20 settlements, including five large cities connected by roads.

Stephen Rostain, an archaeologist at France’s CNRS research Center and the lead author of the study, told the media that it was like discovering the lost mythical city of “El Dorado”.

“The scale of this urban development — which includes earthen homes, ceremonial buildings, and agricultural draining — has never been seen before in the Amazon,” said Rostain who first detected traces of this lost civilization 25 years ago, spotting hundreds of mounds in the area.

In 2015, his team of researchers flew over the region using laser technology called LIDAR, which allowed the scientists to peer through the forest canopy.

Laser mapping paved the way for the discovery

“The LIDAR gave us an overview of the region and we could appreciate greatly the size of the sites,” Rostain said, adding that it showed them a “complete web” of dug roads.

He said the first people who lived there, 3,000 years ago, had small, dispersed houses. However, between approximately 500 BCE and 300-600 CE, the Kilamope and later Upano cultures began to build mounds and set their houses on earthen platforms. These platforms were organized around a low, square plaza.

While we knew about cities in the highlands of South America, like Machu Picchu in Peru, it was believed that people only lived nomadically or in tiny settlements in the Amazon.

“This is older than any other site we know in the Amazon. We have a Eurocentric view of civilization, but this shows we have to change our idea about what is culture and civilization,” Prof Rostain said.

According to the study, data from LIDAR revealed more than 6,000 platforms within the southern half of the 1,000 square kilometers area surveyed. The platforms were mostly rectangular, although a few were circular, and measured about 20 meters by 10 meters (66 feet by 33 feet). They were typically built around a plaza in groups of three or six. The plazas also often had a central platform.

The team also discovered monumental complexes with much larger platforms, which probably had a civic or ceremonial function. They were built by cutting into hills and creating a platform of earth on top.

At least 15 clusters of complexes identified as settlements were discovered. Some settlements were protected by ditches, while there were obstructions to roads near some of the large complexes. This suggests the settlements were exposed to threats, either external or resulting from tension between groups, the researchers said.

Even the most isolated complexes were linked by pathways and an extensive network of larger, straight roads with curbs. In the empty buffer zones between complexes, the team found features of land cultivation, such as drainage fields and terraces. These were linked to a network of footpaths, according to the study.

The overall organization of the cities suggests the existence of advanced engineering at the time, according to the study authors, who concluded that the garden urbanism of the Upano Valley “provides further proof that Amazonia is not the pristine forest once depicted.”

Similar sites found across the Americas

This newly discovered urban network aligns closely with other sites that have been found across the tropical forests of Panama, Guatemala, Belize, Brazil, and Mexico, according to landscape archeologist Carlos Morales-Aguilar, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved in the study.

Terming the study ‘groundbreaking’, he said, “It not only provides concrete evidence of early, advanced urban planning in the Amazon but also contributes significantly to our understanding of the cultural and environmental legacy of Indigenous societies in this region.”

In 2022, Morales-Aguilar was part of a team of researchers that used LIDAR to uncover a vast site in northern Guatemala, with hundreds of ancient, interconnected Mayan cities, towns, and villages, as well as a 110-mile (177-kilometer) network of raised stone trails connecting communities.

He said the findings in this latest study mirror the advanced techniques in agriculture and urban planning that he observed in northern Guatemala and “offer new insights into the complexities of these early societies.”

The discovery changes my perspective on Amazonian culture

“It changes the way we see Amazonian cultures. Most people picture small groups, probably naked, living in huts and clearing land – this shows ancient people lived in complicated urban societies,” said archaeologist Antoine Dorison, co-author of the study.

“The road network is very sophisticated. It extends over a vast distance, everything is connected. And there are right angles, which is very impressive,” he said, explaining that it is much harder to build a straight road than one that fits in with the landscape.

The scientists also identified causeways with ditches on either side which they believe were canals that helped manage the abundant water in the region.

The city was built around 2,500 years ago, and people lived there for up to 1,000 years. According to archaeologists, it is difficult to accurately estimate how many people lived there at any one time, but scientists say it is certainly in the 10,000s if not 100,000s.

Researchers first found evidence of a city in the 1970s, but this is the first time a comprehensive survey has been completed, after 25 years of research. It reveals a large, complex society that appears to be even bigger than the well-known Mayan societies in Mexico and Central America.

“Imagine that you discovered another civilization like the Maya, but with completely different architecture, land use, and ceramics,” said José Iriarte, a professor of archaeology at the University of Exeter, who was not involved in this research.

Some of the findings are ‘unique’ for South America, he explained, pointing to the octagonal and rectangular platforms arranged together. The societies were well-organized and interconnected, as the long sunken roads between settlements indicate.

People who lived there

Not a huge amount is known about the people who lived there and what their societies were like. Pits and hearths were found in the platforms, as well as jars, stones to grind plants and burnt seeds. The Kilamope and Upano people living there probably mostly focused on agriculture. People ate maize and sweet potato and probably drank “chicha”, a type of sweet beer.

Professor Rostain was warned against this research at the start of his career because scientists believed no ancient groups had lived in the Amazon. “But I’m very stubborn, so I did it anyway. Now I must admit I am quite happy to have made such a big discovery,” he said.