Two years have passed since the military junta in Myanmar, led by Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, seized power in a coup and detained the elected civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other members of her National League for Democracy (NLD) party. Since then, the junta has unleashed a brutal crackdown on the pro-democracy movement, killing more than 1,500 civilians, arresting thousands more, and displacing millions from their homes. The junta has also continued its decades-long persecution of the Rohingya Muslim and denies their citizenship and basic rights. The junta has accused the Rohingya of being terrorists and blamed them for the country’s problems, while blocking humanitarian aid and repatriation efforts for the hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled to Bangladesh after the military’s atrocities in 2016 and 2017.

You can also read: Myanmar Unrest Concerns Neighbors

The people of Myanmar have been fighting for their freedom and democracy, facing violent repression and human rights abuses. But in the midst of this dark and bloody conflict, there is a ray of hope and a sign of unity. A recent development has highlighted a show of previously unseen unity; with various factions uniting under the single purpose of toppling the military junta.

A History of Division and Discrimination

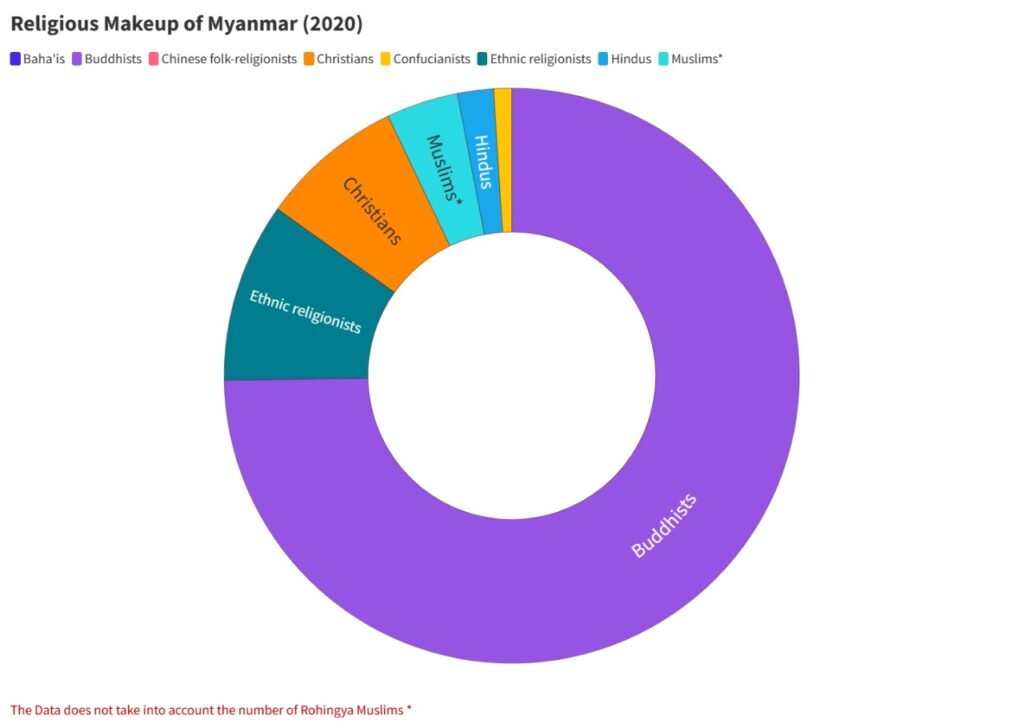

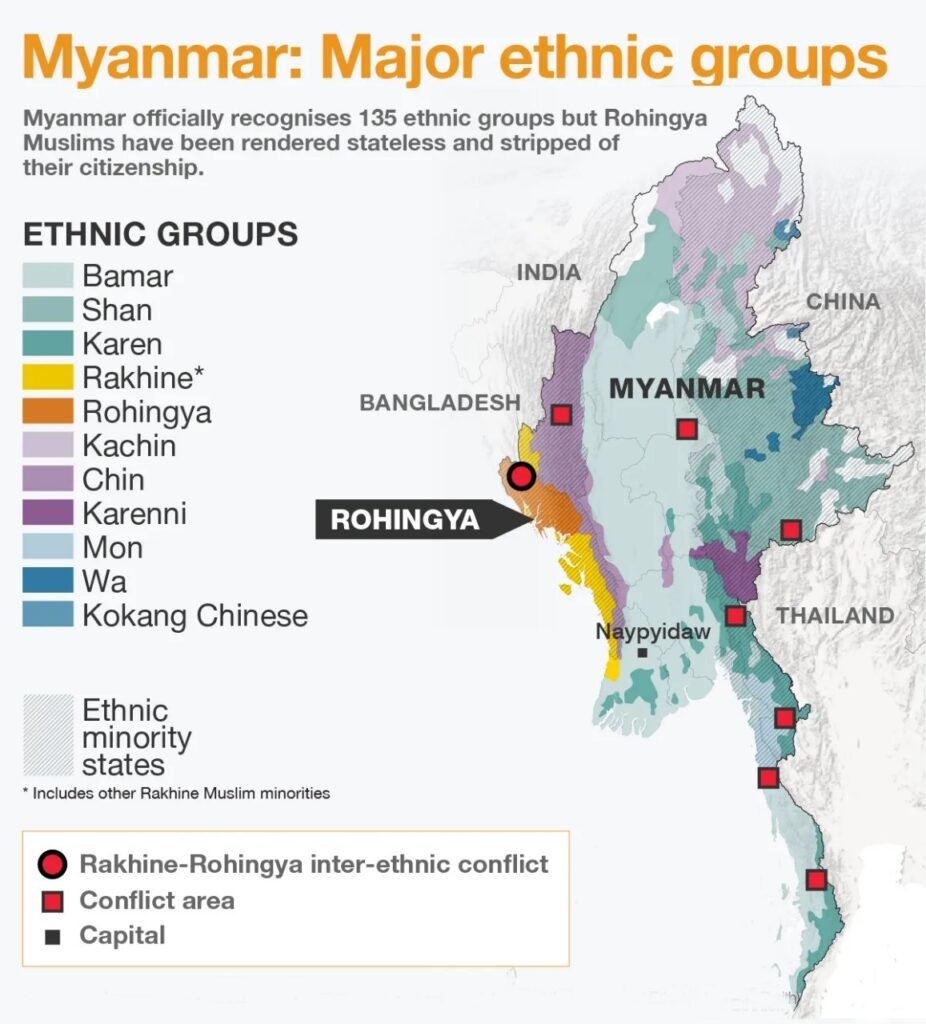

Myanmar, also known as Burma, boasts a diverse cultural heritage but has been marred by a tumultuous history of division and discrimination. Home to approximately 130 ethnic groups, the Bamar stands as the largest, constituting 68 percent of the population and wielding significant political and economic influence. Primarily followers of Theravada Buddhism, the Bamar’s dominance is reflected in the country’s official religion. While 90 percent of the population adheres to Buddhism, the remainder comprises Christians, Muslims, and various other religious affiliations.

In the latest estimations ON 2020, around 88% identify as Theravada Buddhists, while Christians, encompassing Baptists, Roman Catholics, and Anglicans, make up about six percent. A four percent slice is attributed to Muslims, primarily Sunni. It’s crucial to note that the 2014 census didn’t include Rohingya, but both NGOs and the government approximated their Sunni Muslim population at 1.1 million before October 2016. Shockingly, as of September 2023, 965,467 Rohingya refugees have been registered and issued documentation jointly by the Government of Bangladesh and UNHCR. These refugees have sheltered in Bangladesh since August 2017, with an estimated 520,000 to 600,000 still in Rakhine State.

The roots of Myanmar’s ethnic and religious conflicts trace back to the colonial era when British rule, spanning from 1824 to 1948, exacerbated existing divisions by favoring certain groups. Exploiting ethnic differences bred resentment and mistrust, while the suppression of Buddhist practices in favor of secular education ignited a nationalist movement among Bamar Buddhists. This movement birthed the Burma Independence Army in 1941, laying the foundation for the junta’s army. Although Myanmar gained independence in 1948, ethnic and religious tensions persisted.

Post-independence, Bamar Buddhist elites sought to impose their dominance, perpetuating marginalization and oppression of ethnic and religious minorities. Former Prime Minister U Nu encapsulated this ideology with his slogan: only the Bamar race, only the Burmese language, and only the Buddhist religion. This ideology fueled the world’s longest civil war, erupting in 1948, as ethnic minorities fought for their rights and autonomy, while the junta responded with brutal force.

The junta’s persecution extended to non-Buddhist minorities, with a particular focus on Rohingya Muslims, denied citizenship and basic rights. The Rohingya faced genocide, enduring killings, rapes, and mass displacements orchestrated by the junta. Propaganda and hate speech were wielded as weapons, inciting violence and animosity against the Rohingya and other non-Buddhists, portraying them as threats and enemies.

A New Dawn of Hope and Unity

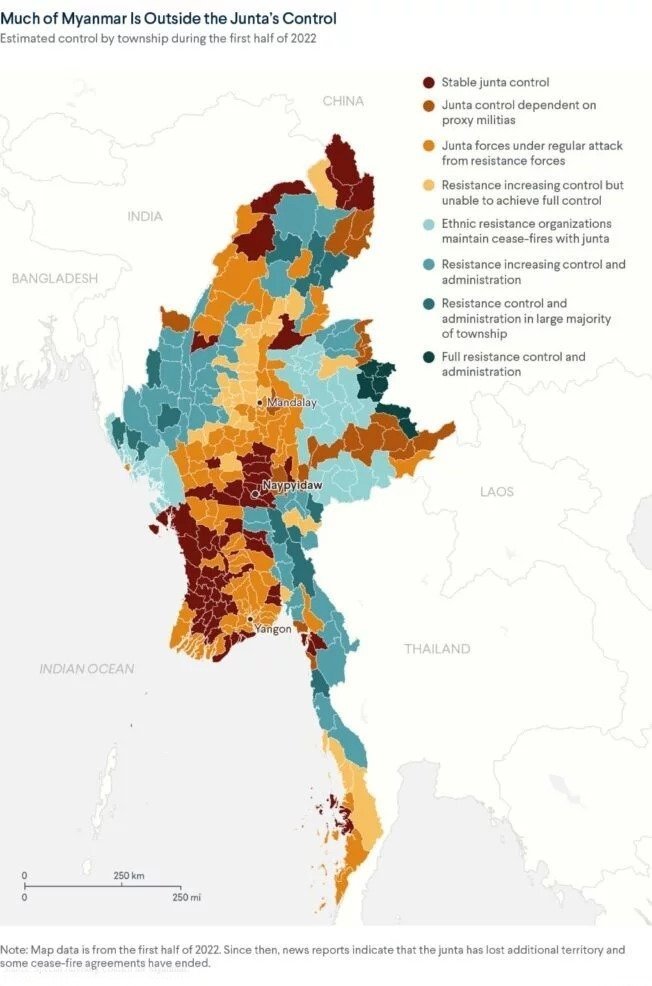

The junta’s oppressive rule and deceptive narratives have not gone unopposed. The resilient people of Myanmar, hailing from diverse ethnic, religious, and social backgrounds, have come together in resistance against the military dictatorship and its false claims. A parallel entity known as the National Unity Government (NUG), comprising ousted lawmakers, ethnic leaders, and civil society activists, has emerged, asserting itself as the legitimate representative of the people. To undermine the junta’s authority and revenue, the people have orchestrated a multifaceted approach, including a civil disobedience movement, a people’s defense force, and a clandestine shadow economy. Notably, they have expressed solidarity with the persecuted Rohingya, rejecting the junta’s divisive campaign.

The people of Myanmar have exhibited extraordinary courage and resilience in their quest for democracy and human rights. Despite facing violent repression from the junta, they have taken to the streets, initiated strikes, boycotted businesses, and employed creative and peaceful methods to voice their dissent and demand the reinstatement of civilian rule. Utilizing social media, underground channels, and alternative communication platforms, they have disseminated information, exposed the junta’s crimes, and coordinated their efforts. Drawing inspiration from regional and global movements for freedom and justice, the people have formed a united front against tyranny.

The inclusive and diverse nature of the people’s resistance mirrors the intricate fabric of Myanmar’s society. Individuals from various ethnic groups — Bamar, Karen, Kachin, Chin, Shan, and Mon — who have long endured the military’s oppression, join hands in this struggle. Moreover, the resistance has bridged gaps between different religious communities — Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and Hindus — who were often manipulated against each other by the junta’s propaganda. Empowering women, youth, workers, students, artists, journalists, and other marginalized groups, the movement has proven that Myanmar’s people are not divided by their differences but united by shared aspirations for democracy, peace, and dignity.

The junta’s false campaign

One of the main targets of the junta’s repression and propaganda has been the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group that lives mostly in the Rakhine state of western Myanmar. The junta has denied the Rohingya’s identity, history, and rights, and has portrayed them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh who pose a threat to the country’s security, stability, and sovereignty. The junta has also accused the Rohingya of being involved in terrorist activities, and has used this as a pretext to launch brutal military operations against them, resulting in mass killings, rapes, torture, arson, and displacement. The junta has also blocked humanitarian access and independent investigations into the situation in Rakhine, and has refused to cooperate with the international efforts to hold it accountable for its crimes against humanity and genocide.

However, the junta’s campaign against the Rohingya is based on lies and distortions. The Rohingya are not foreigners, but indigenous people of Myanmar, who have lived in the country for centuries and have contributed to its culture and society. The Rohingya are not terrorists, but victims of state-sponsored violence and persecution, who have been denied their basic rights and freedoms. The Rohingya are not the cause of the country’s problems, but the scapegoats of the junta’s failures and corruption, who have been used to divert attention from the real issues and challenges facing the country. The Rohingya are not the enemy of the people, but the fellow citizens and brothers and sisters of the people, who share the same dreams and hopes for a better future.

The impact on Bangladesh

The junta’s anti-Rohingya policy has not only caused immense suffering and injustice for the Rohingya, but also created serious problems for Bangladesh, the neighboring country that hosts the majority of the Rohingya refugees. According to a September 2023 UNHCR estimate, there are nearly a million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, most of whom live in overcrowded and squalid camps in the Cox’s Bazar district, near the border with Myanmar. The Rohingya refugees face multiple challenges and risks, such as lack of adequate food, water, health, education, and protection services, as well as exposure to natural disasters, diseases, violence, trafficking, and exploitation. The Rohingya refugees also face uncertainty and anxiety about their future, as they long to return to their homes in Myanmar, but fear for their safety and security.

The presence of such a large number of refugees has also put a huge strain on Bangladesh’s resources, infrastructure, environment, and social cohesion. Bangladesh has shown remarkable generosity and hospitality in welcoming and hosting the Rohingya refugees, and has received praise and support from the international community. However, Bangladesh cannot and should not have to bear this burden alone. It needs more assistance and cooperation from other countries and organizations to address the humanitarian and development needs of the refugees and the host communities. Bangladesh also needs more diplomatic and political pressure on Myanmar to create the conditions for the voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable repatriation of the Rohingya refugees, in accordance with their rights and wishes.

The role of the international community

The international community has a moral and legal responsibility to support the people of Myanmar in their fight against the junta and its false campaign, and to protect the Rohingya and other vulnerable groups from the junta’s atrocities.

The people of Myanmar have shown remarkable courage and resilience in their resistance against the junta and its false campaign against the Rohingya. They have united in their diversity and expressed solidarity with their fellow citizens and brothers and sisters. They have challenged the junta’s tyranny and lies, and demanded the restoration of civilian rule and the recognition of their rights and dignity.

The international community should stand with the people of Myanmar and support their struggle for democracy and human rights. The international community should also hold the junta accountable for its crimes against humanity and genocide, and pressure it to end its repression and persecution of the Rohingya and other vulnerable groups. The international community should also help the people of Myanmar to achieve a peaceful and inclusive transition to democracy.