The horrors of genocide have marred humanity’s history for centuries, leaving indelible scars on the collective memory of those who have suffered its brutal consequences.

Recent events in Bucha, Ukraine, once again thrust the issue of genocide into the global spotlight, raising questions about Western responses to such atrocities. While the international community swiftly condemned the Bucha massacre as a genocide, millions of Bangladeshis are left pondering why the genocide they endured in 1971 remains largely unrecognized by the West.

You can also read: The Rohingya genocide: is ICJ soft on Myanmar Case?

The tragedy of Bangladesh’s 1971 genocide is often overshadowed by geopolitical interests, preventing the world from acknowledging the magnitude of the suffering experienced by the Bangladeshi people during their quest for independence.

Recognizing the Genocide

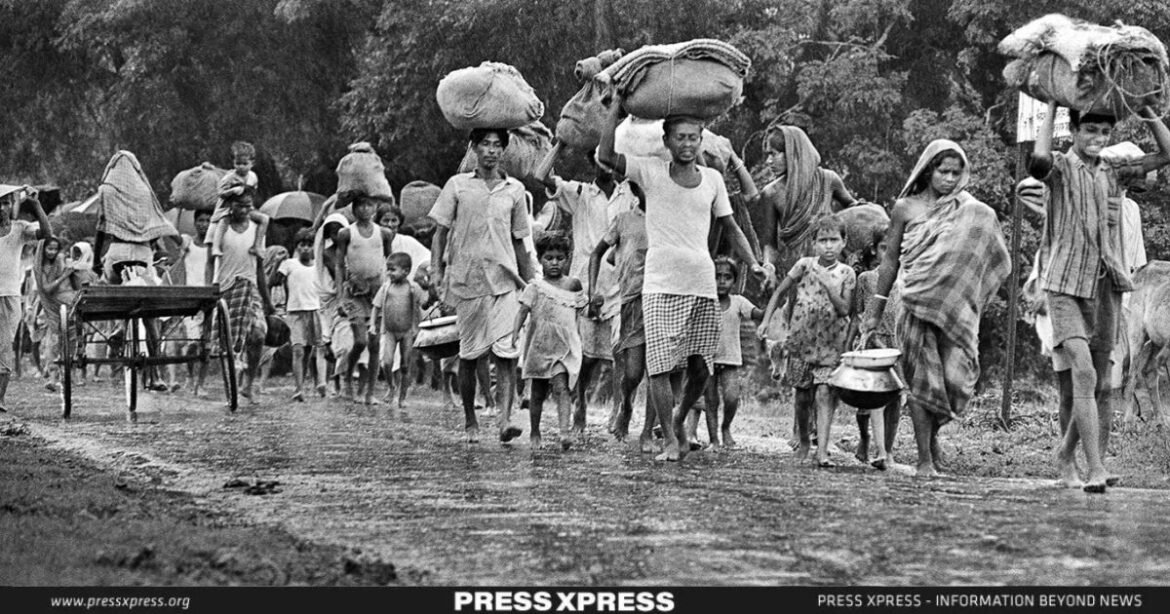

Over the course of nine months, the Pakistani military’s brutal campaign resulted in the deaths of approximately three million people and the rape of over 200,000 women. Moreover, more than 10 million people were forced to flee to India as refugees, and nearly half of Bangladesh’s population was internally displaced.

On May 20, 1971, over a period of six hours between 11am and 5pm, at least 10,000 people (eye witnesses claim the number is much higher), were subjected to wanton killing at Chuknagar, a small township in Khulna district. Pakistani soldiers raided Chuknagar to carry out a brutal carnage. Bhadra, the small river flowing through Chuknagar, went red with the blood of the fallen. Most of the dead bodies found their “graves” on the river’s bed.

The Chuknagar incident is only one of hundreds of such genocidal episodes that took place during the nine-month-long war of independence.

These Cold-blooded mass murders are well-documented, and there was no shortage of evidence at the time. In April 1971, the US Consulate in Dhaka reported to the State Department that East Pakistan was in the midst of a genocide, condemning their own government’s “moral bankruptcy” in the face of these horrors.

The number of individuals massacred in then-East Pakistan between March and December 1971 by Pakistani forces (the regular army and collaborators) greatly outnumber those who perished in the three genocides recognized by the UN. In Cambodian Genocide, about 1.5 to two million were killed at the hands of the murderous Khmer Rouge over four years (1975 and 1979). Between April and August 1994, during the Rwandan civil war, between 500,000 and 650,000 Tutsis were murdered by Hutus. Moreover, the death toll from the Balkan genocide never exceeded six figures.

Despite ample evidence and courageous reporting by journalists such as Anthony Mascarenhas, Simon Dring, and Sydney Schanberg, the Western world remained largely indifferent to the plight of the Bengali people. Even renowned musicians like Joan Baez and George Harrison used their platforms to raise awareness through “Song of Bangladesh” and the “Concert for Bangladesh,” respectively. Yet, the Western powers remained passive, revealing a severe disconnect between their proclaimed values and their actions.

Gary J. Bass’ book, “The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger and a Forgotten Genocide,” exposes the tragic underpinnings of President Richard Nixon and Foreign Secretary Henry Kissinger’s role in dismissing the Bangladesh genocide as “collateral damage” during their pursuit of a rapprochement with China. This calculated approach, prioritizing geopolitical interests over human lives, is a stain on the moral conscience of the world.

Bangladesh Genocide Diplomacy

After the liberation war, Bangladesh had to overcome new struggles to establish itself in the global community and be vocal about its sufferings at the same time. According to a paper by International Court of Justic, Over 92,000 Prisoners of War from Pakistan, which included between 79,676 and 81,000 members of the Pakistan Armed Forces in uniform, were apprehended by Indian authorities, as well as a contingent of Bengali soldiers who had maintained their allegiance to Pakistan. Bangladesh could not prosecute over these surrendered Pakistani soldiers, including the accused 195 war criminals as it was yet to be a member of the UN and the Geneva Conventions of 1949. Bangladesh was initially denied UN membership because Pakistan used its alliance with China to exercise a veto in the UN Security Council.

Bangladesh’s separation from Muslim-majority Pakistan was not taken well by other Muslim nations. As a newly formed country, Bangladesh has to evaluate the cost of these geopolitical interests of involved states and the intricacies of the cold war era against the urgency of getting global recognition as an independent country, obtaining UN membership, and access to foreign aid. These geopolitical pressures and cost-benefit considerations kept Bangladesh to internationalize the genocide perpetrated by the Pakistani army and its auxiliary forces.

Since the 1990s, along with various civic groups the Bangladesh government, led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, is continuing its earnest efforts to gain worldwide acknowledgment for Bangladesh’s genocide. The government has made efforts to document the genocide, preserve the testimonies of survivors, and raise awareness internationally about the events that transpired. The initiatives may have begun with a quest for acknowledgment and justice for atrocities committed in Bangladesh. Yet, under Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s resolute leadership, the campaign for genocide recognition has become part of Hasina’s statecraft.

The Slow Turning Wheels of Justice

Despite decades of indifference, there is now a glimmer of hope on the horizon. International organizations like Genocide Watch, Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention, International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, and International Association of Genocide Scholars have called upon the UN and the international community to recognize the Bangladesh Genocide of 1971.

The recent bipartisan resolution submitted by US Congressmen Steven Chabot and Ro Khanna to recognize the genocide demonstrates a promising shift in the Western stance. (The Daily Star, October 18, 2023).

Bangladesh has also taken significant steps to commemorate its history, designating March 25 as Genocide Day and pressing for international recognition. In the last few years, the Bangladesh Genocide issue has been discussed at side events during the International Human Rights Council sessions, garnering more attention.

The Western world’s proclaimed values of freedom, democracy, human rights, and a rules-based world order appear hollow when its response to genocide is selective. It is high time for the West to align its actions with its stated principles. In an evolving global landscape where unipolarity is waning, rebuilding trust between the West and the Global South necessitates addressing past injustices.

Bangladesh’s struggle for recognition of the 1971 genocide is one such case, where the line between right and wrong is undoubtedly clear-cut. As Archer K. Blood, the US Consul General in Dhaka during the genocide, stated, “I paid a price for my dissent. But I had no choice. The line between right and wrong was just too clear-cut.”

We can reasonably hope, after 52 years, that the UN, the US, and other countries will finally see this line clearly and acknowledge the Bangladesh Genocide of 1971 as one of the darkest chapters in human history, deserving international recognition.