Merely a month following China’s proclamation of restricting the export of gallium and germanium, vital components indispensable in semiconductor manufacturing, their overseas shipments dropped to zero. Beijing has granted some export licenses in the interim, yet these restrictions serve as an ominous reminder that China possesses a potent weapon in the escalating trade war concerning the future of technology. These constraints were a response to limitations placed by the United States, Europe, and Japan on chip and chipmaking equipment sales to China. This was aimed at cutting off China’s access to critical technology that could be repurposed for military applications.

You Can Also Read: HAMAS ATTACK CASTS SHADOW ON INDIA’S GLOBAL TRADE VISION

China’s export restrictions highlight the potential severity of limitations on gallium and germanium exports from China and the challenges in establishing an alternative supply chain. This also underscores the potential economic and technological challenges associated with reducing dependency on China for gallium and germanium supply.

The restrictions on gallium and germanium exports raise several critical concerns, including:

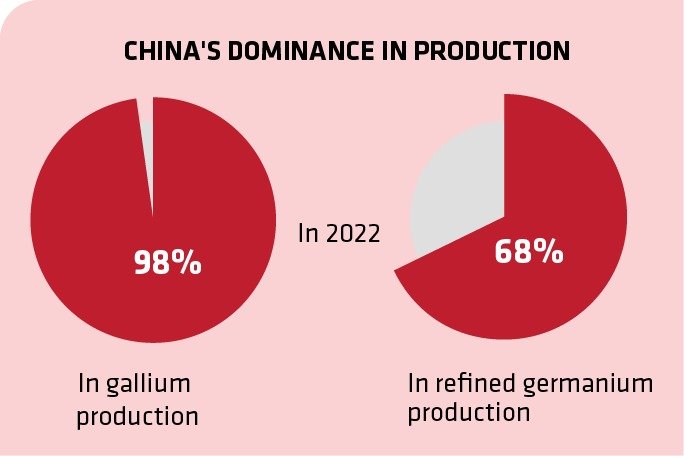

- China’s Dominance in Production: China is a major player in the production of gallium and germanium, commanding a significant share of the global market. According to data from the US Geological Survey, it produced 98% of Global gallium and 68% of refined germanium production in the previous year.

- Potential Supply Chain Disruption: If China were to block a substantial portion of exports of these elements, it could disrupt the global supply chain, causing significant issues for consumers and industries that rely on these materials.

- Challenges of Establishing an Alternative Supply Chain: While the United States and its allies may consider exploring alternatives to China’s supply, doing so would require a massive investment exceeding $20 billion. Additionally, developing a new supply chain for gallium and germanium processing would take years.

- Time and Technology Constraints: The refinement technologies and facilities necessary for gallium and germanium processing cannot be developed overnight. It’s a time-consuming process, and the extraction and mining processes also have environmental implications that need to be considered.

Nevertheless, there appears to be no alternative but to embark on this formidable endeavor. While the monetary value of these minerals in global trade may be relatively modest, only amounting to “several hundred million dollars,” they play a pivotal role in the supply chains of international semiconductor, defense, electric vehicle, and communication industries. Each of these industries is worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

From byproducts to dominance

For over a decade, China has dominated the production of two crucial elements: gallium and germanium. Gallium, a malleable, silvery metal, is vital for radio frequency chips in mobile phones and satellite communication. Germanium, a hard, grayish-white metalloid, plays a key role in optical fiber production for transmitting light and electronic data. These elements are byproducts of aluminum, zinc, and copper mining.

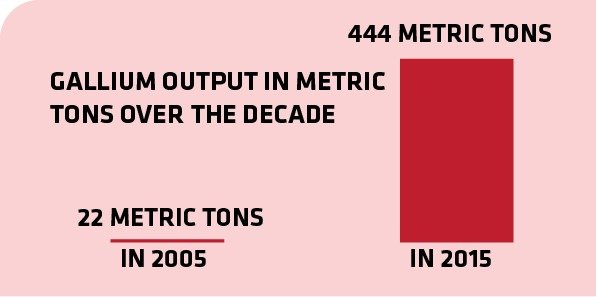

Refining gallium and germanium is a complex and resource-intensive process. China’s supremacy in its production is not solely due to its scarcity but also stems from its ability to keep production costs remarkably low, outpacing competitors. Between 2005 and 2015, China’s low-purity gallium output surged from 22 to 444 metric tons. Analysts attribute this to China’s strong position in the aluminum industry and strategic government policies that encouraged gallium extraction.

As a result, gallium production outside of China became economically unviable over the past decade, leading countries like Kazakhstan, Hungary, and Germany to cease their primary gallium production operations. However, Germany expressed plans to restart production in 2021 due to rising prices. China’s dominance in gallium and germanium production underscores its influence on the global supply chain, driven by economic efficiency and strategic policies.

Russia, Canada, and more in the play

Nonetheless, alternatives do exist.In 2022, according to data from the US Geological Survey (USGS), Russia, Japan, and Korea collectively contributed 1.8% of the global gallium production. Canada’s Teck Resources stands as one of the world’s largest germanium producers, and the American company, Indium Corporation, ranks among the top global manufacturers of germanium compounds and alloys. Canada’s 5NPlus and Belgium’s Umicore have entered the arena by producing both of these critical elements.

However, the transition to these alternative sources is no overnight endeavor, cautions Chris Miller, the author of “Chip War” and an esteemed economic historian. It’s not just a matter of time; it’s also a question of cost.

Gregory Allen, the Director of the Wadhwani Center for AI & Advanced Technologies at CSIS, unveils a potential path forward. Global mining giants can enter the fray and supply gallium and germanium should China choose to tighten its grip on themarket. “This process won’t be immediate,” he clarifies, “but certain global mining and refining companies have signaled their intent to do so.” A bold move, indeed.

In a bold move signaling readiness, the Russian state-owned conglomerate Rostec has expressed its willingness to escalate germanium production for domestic consumption, responding to China’s export restrictions. Netherlands-based Nyrstar, too, is setting its sights on potential gallium and germanium ventures across Australia, Europe, and the United States, further underscoring the global resolve to diversify supply sources.

In the face of these challenges, Xiaomeng Lu from Eurasia Group offers a glimmer of hope. She points out that even if supplies of these invaluable minerals were to run dry, gallium could step in as a substitute for silicon or indium in the wafer manufacturing process. Additionally, she highlights zinc selenide as a capable, though lesser-known, alternative to germanium in specific applications, leaving a trail of innovation and adaptability amidst this landscape of change.

Costs on the rise

In a commendable move, the US Defense Logistics Agency launched a program last year to recycle optical-grade germanium used in weapon systems. Xiaomeng Lu sheds light on the existing sources of supply, revealing that factory floor scrap already contributes to the resource pool. Notably, germanium scrap is salvaged from decommissioned military vehicles, including tanks, offering a valuable reservoir.

In the shadow of a challenging August, when China halted gallium and germanium exports beyond its borders, there emerges a glimmer of hope for September. The Chinese Commerce Ministry has announced the approval of export licenses for domestic companies, hinting at a potential resurgence in the numbers.

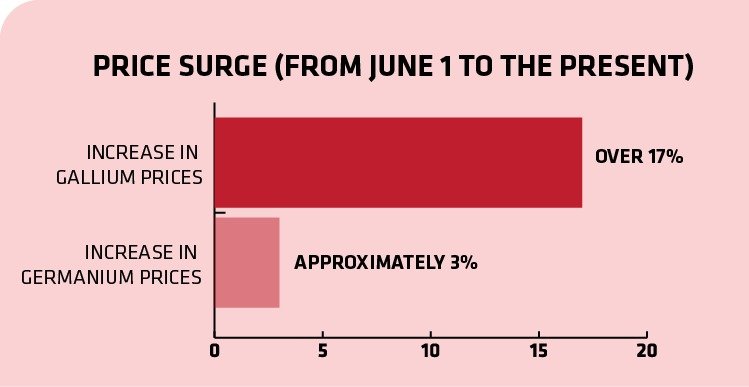

However, in the interim, it’s undeniable that prices for these indispensable elements are set to ascend, forewarns EwaManthey. As of Tuesday, gallium prices reached 1,965 yuan ($269) per metric ton, marking a remarkable surge of over 17% since June 1, as reported by ebaiyin.com, a Chinese metal trading service website. Meanwhile, germanium prices have also undergone an upward trajectory, escalating by approximately 3% during the same period.