Instead of targeting Latin Americans for blame, they should get assistance to help them address the issues arising from drug prohibition and drug abuse in their countries. All possibilities, from decriminalization to the regulation and taxation of the drug trade, should be on the table for discussion.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro has suggested the formation of a coalition among Latin American nations to address drug trafficking with a united front. He advocated for the recognition of drug consumption as a public health issue instead of persisting with what he has labeled an “unsuccessful” militarized approach during the closing of the Latin American and Caribbean Conference on Drugs “For Life, Peace and Development” on September 9, 2023.

Bringing the Latin American and Caribbean Conference on Drugs in Cali to an end, Petro, Colombia’s first-ever leftist president, argued that 50 years of a failed drug war had left Latin America scarred by incalculable bloodshed. He also stated that it had caused immense suffering.

You can also read: The Complex Dynamics Behind Ukraine’s Reluctance for Ceasefire

“I suggest that we adopt a fresh and cohesive perspective to advocate for our society, safeguard our future, and honor our history while breaking free from the confines of an unsuccessful narrative. The time has come to rekindle hope and refrain from perpetuating the painful and brutal wars, such as the ill-conceived ‘war on drugs,’ which wrongly perceives drugs as a military issue rather than a public health concern,” he conveyed.

The rise of the drug trade in Colombia

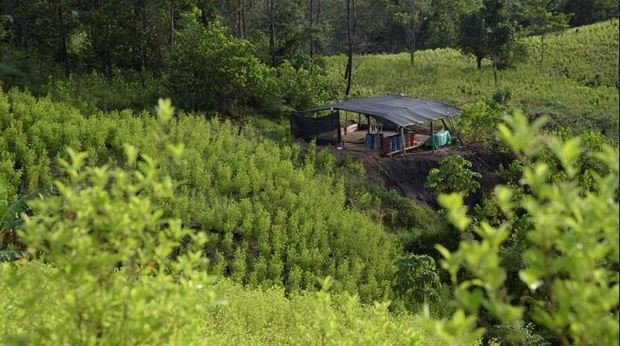

Over the years, Colombia has been home to four major drug trafficking cartels – Medellín, Cali, Norte del Valle, and North Coast – each playing a significant role in the illegal drug trade since the 1970s. The surge in coca production in Colombia was driven by the worldwide appetite for psychoactive drugs in the 1960s and 1970s, solidifying Colombia’s position as the top producer.

Colombia experienced a surge in drug production during the pandemic, with the total coca leaf cultivation area expanding by 43% in 2021, as reported in the latest annual survey by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Simultaneously, the potential coca yield per hectare increased by a further 14%.

According to the UN, as a consequence of pandemic lockdowns, illicit drug production became the predominant economic activity in numerous rural regions of the country. This shift occurred as markets and agricultural routes closed down, prompting farmers to switch from food crops to coca.

How has the U.S. war on drugs shaped Latin American countries?

Cocaine, manufactured in remote Colombian labs at a mere $1,500 per kilo, can be resold on US streets for as much as $50,000 per kilo. The US, the largest global consumer of cocaine and illicit drugs, engaged in efforts to disrupt this supply chain in Colombia.

Since the War on Drugs was declared, the governments of the United States and various European nations have been providing Colombia with financial, logistical, tactical, and military aid to carry out anti-drug strategies. United States-led initiatives to combat drug trafficking in Latin America contribute to increased violence, lawlessness, corruption, and instability across the region.

Drug prohibition policies endorsed by the U.S. gave rise to an extensive underground drug market, ultimately bolstering and empowering organized crime syndicates, corrupt officials, and warring factions.

The practice of anti-drug fumigation, like the U.S. financial and military resources against coca and poppy crops in Colombia, has been linked to documented adverse effects on both human health and the environment. The imprecise nature of the spraying poses significant risks to people, livestock, and food crops.

Challenging the influence of cocaine

Over the past fifty years, Colombia has faced the daunting challenge of convincing farmers to abandon coca cultivation. The conventional approach to this issue in Colombia has involved punishing farmers by employing increasingly sophisticated and forceful methods, such as aerial fumigations, enforced eradication campaigns, aerial monitoring, and the deployment of troops to coca-growing areas.

However, the financial burden of this endeavor reached into the millions, with substantial support from military aid offered by the United States to Colombia. Sadly, it has also led to the loss of thousands of Colombian farmers and soldiers in conflicts and drug-related violence.

Petro’s administration seeks to curb the escalation of drug-related violence, even if it entails potential growth in coca harvesting areas in the near future, in the short run.

In an effort to sidestep confrontations with coca-growing communities and lessen the likelihood of retaliatory actions from cartels, Colombia’s coca eradication campaign will be toned down, though not entirely suspended. Instead, the justice ministry will initiate a series of ‘voluntary consultations’ aimed at convincing these communities to replace illicit crops with legal alternatives, all while providing financial incentives.

Drug cartels, the purchasers of coca, are prepared to offer advance payments for a crop, frequently in cash, and critically, they ensure transportation by directly collecting it from the farms– a compelling inducement for farmers located hours away from major market towns. This is why the Petro government is determined to relocate the entire workforce associated with cocaine production.

Critic’s take on the matter

A 2019 study carried out by the University of Oxford revealed that Colombia’s drug trade accounts for almost 2% of its GDP. Osuna is well aware of the arduous task at hand, acknowledging that resolving this issue won’t be a quick fix, considering the fifty-year history of failed efforts in the war on drugs.

The government’s opponents, like former Colombian president Alvaro Uribe, oversaw the most significant crop reduction in the nation’s history through a contentious, full-scale military operation in the early 2000s. He argued that legalizing cocaine would only increase the wealth of the cartels, not diminish it.

As a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, Santos highlighted the necessity of a comprehensive approach, stating: “It’s high time we address responsible government regulation, seek strategies to disrupt the drug trade, and bolster resources for prevention, care, and harm reduction in relation to public health and our societal fabric. To be truly effective, this reflection should encompass a global perspective, engaging not just governments but also academia and civil society. It should extend its reach beyond law enforcement and the judiciary, involving experts from various fields such as public health, economics, and education.”