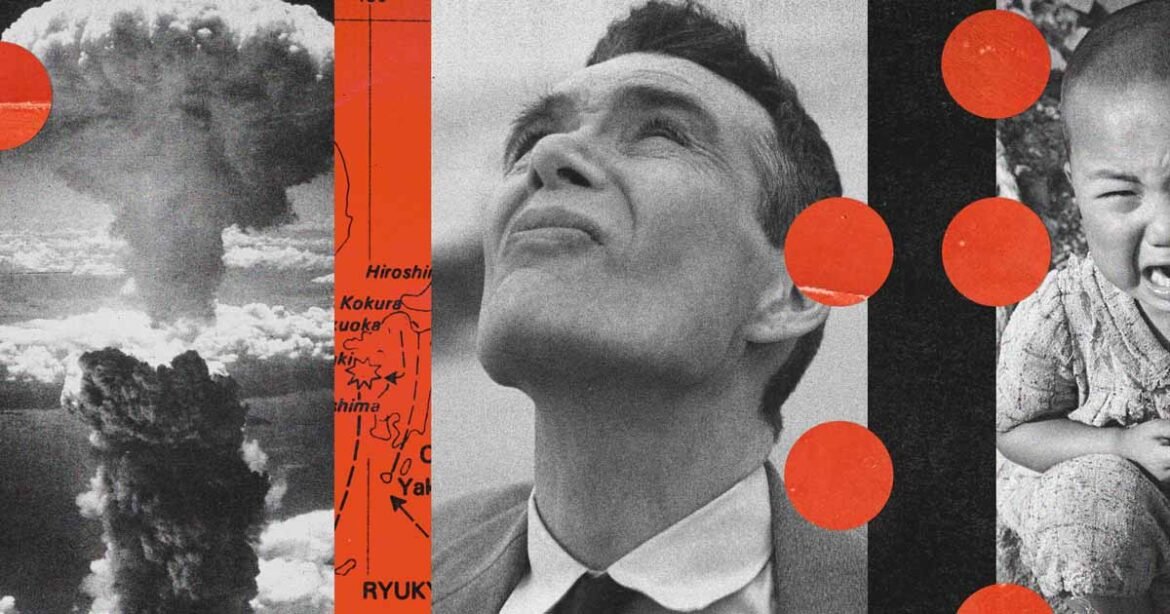

Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster biopic was released in the US shortly after the anniversary of the Trinity test, which marked the culmination of the Manhattan Project on July 16, 1945. This significant event paved the way for the post-war Pax Americana. In South Korea, the film was scheduled to hit screens on National Liberation Day, which commemorates Tokyo’s surrender on August 15, 1945, at the end of World War II, an event for which the atomic bomb is often credited. However, in Japan itself, where the nation is nearing the 78th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bombs “Little Boy” and “Fat Man” on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, the movie has not yet been scheduled for release.

The absence of a release date in Japan may reflect the country’s complex and sensitive views on the war. In the US, the movie has sparked debates on whether the use of the atomic bomb during World War II constituted a war crime. These discussions, based on historical revisionism and modern perspectives, have proven to be contentious. Contrary to some reports, it is important to note that the film “Oppenheimer” has not been banned in Japan. Unlike some of its Asian neighbours, Japan rarely takes such steps to ban politically sensitive content. However, the movie’s distributor has not yet confirmed a release date for Japan, and if it does happen, it is likely to be scheduled after the August 6 and August 9 memorials, which commemorate the atomic bombings.

Japan tends to avoid extensive discussions about the rights and wrongs of the atomic bombings, particularly on the anniversaries of these events. The citizens’ views on the matter are diverse, with no uniform position among the Japanese population. In a 2015 survey conducted by the public broadcaster NHK in Japan, it was found that approximately 40% of the Japanese population concurred with the statement suggesting that the United States had no alternative but to utilize the atomic bomb. Interestingly, in Hiroshima, that number was slightly higher at 44%, surpassing the national average, and there were more individuals who labelled the bombing as “unforgivable.” These findings suggest that opinions on the bombings continue to vary among the Japanese people.

Revisiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Residents were recently asked for their opinions on the US decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, when local audiences get the chance to watch the movie, it may spark a different discussion, focusing on Japan’s ambiguous and sometimes contradictory stance toward nuclear weapons. Publicly, Japan opposes nuclear technology, but it also relies on it for its security, given the increasingly hostile neighbourhood. As the country faces a significant shift in defense spending, it becomes essential to address this debate now.

Headlines from Kyodo News during Oppenheimer’s US premiere often reflect a common sentiment on both sides of the Pacific, expressing concern that the movie fails to depict the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan’s own portrayals of historical events also tend to lack the same level of context, often emphasizing sentimental depictions of the experiences of the common people affected by the events. The atrocities suffered by Japan during the war and those committed by Japan elsewhere are sometimes treated as though they were natural disasters.

Rather than rehashing old arguments, it may be more prudent to focus on the current state of affairs. While the US continues to contemplate its decision to use the atomic bomb, Japan has largely accepted the post-war reality. In recent surveys, it has been reported that an unprecedented 90% of the Japanese population now expresses their admiration for the US-Japan alliance, recognizing its vital role in safeguarding the nation’s peace and security. This remarkable figure reflects a consistent upward trend over the past four decades.

The impact of Abe’s proposal and Kishida’s rejection

Respondents were recently asked for their opinions on whether the Japan-US Security Treaty contributes to the peace and security of Japan. Last year, Tokyo came close to initiating a serious debate about its three non-nuclear principles, which commit the government to not possessing, producing, or allowing atomic weapons to enter the country. In early 2022, Shinzo Abe, a prominent voice in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party and a former prime minister, suggested the need to discuss the possibility of hosting US nuclear weapons in Japan. Abe’s statement sparked controversy and concern, particularly regarding the potential remilitarization of Japan.

Despite the passage of time, this debate has not faded away entirely. The idea of weapon sharing was strongly rejected by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, a lifelong advocate for denuclearization, whose family has roots in Hiroshima, a city devastated by the atomic bomb. Abe’s assassination before he could capitalize on Kishida’s limited public support has contributed to the lack of significant progress in the discussion.

In May, Prime Minister Kishida took the leaders of the Group of Seven (G7) nations to visit the aftermath of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. During this visit, the G7 leaders pledged to work towards a world without nuclear weapons while ensuring undiminished security for all. This stands in contrast to the concerns expressed by former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the same month, who has repeatedly warned that Japan is on a path to becoming a nuclear power within the next five years. Kissinger’s longstanding concerns revolve around the potential for a remilitarized Tokyo and have led him to advocate for closer cooperation between the US and China to mitigate such possibilities.

The issue of Japan’s stance on nuclear weapons and its reliance on the Japan-US Security Treaty remains a contentious and complex topic. Public opinion in Japan and the views of its political leaders continue to shape the ongoing debate about the country’s security and nuclear policies.

Indeed, Prime Minister Kishida should not be too quick to dismiss the discussion about Japan’s security and nuclear policies. In an increasingly uncertain world, where tensions between the US and China are on the rise, Japan must be willing to engage in real talks about its response strategy, including the role of atomic weapons, and what actions it would take if the US nuclear umbrella were no longer guaranteed, especially under a less reliable administration.

Recent events, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have shattered some post-Cold War assumptions, demonstrating that the global geopolitical landscape is evolving rapidly. In light of the growing tensions around Taiwan, Japan cannot afford to remain stagnant in decades-old debates. It must actively consider and prepare for potential challenges and threats in the current geopolitical climate.

While “Oppenheimer” may have sparked unhelpful reinterpretations of World War II, if the movie reaches audiences in Japan, it could serve as a catalyst for a more productive and meaningful discourse within the country. As a nation that experienced the horrors of atomic bombings firsthand, Japan has unique perspectives and responsibilities when it comes to discussions on nuclear weapons and war.