With Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s renewed threat to abandon the Black Sea deal on Tuesday, the outlook of the deal is “not so great” for extending beyond May 18, 2023. As a result, uncertainty reigns over the future of the United Nations-backed sea corridor, which allows for the safe export of grain from some Ukrainian Black Sea ports during the war.

The fundamental food security of tens of millions of people around the world hangs by a thread as Russia mulls whether it will maintain an agreement that has allowed Ukrainian grain to pass through the Black Sea. On Tuesday, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov reiterated his threats to abandon the Black Sea Grain Initiative because the conditions for extending the guarantee of safe exports via the Black Sea during the Ukraine conflict had not been fulfilled.

The black sea grain initiative and its renewal

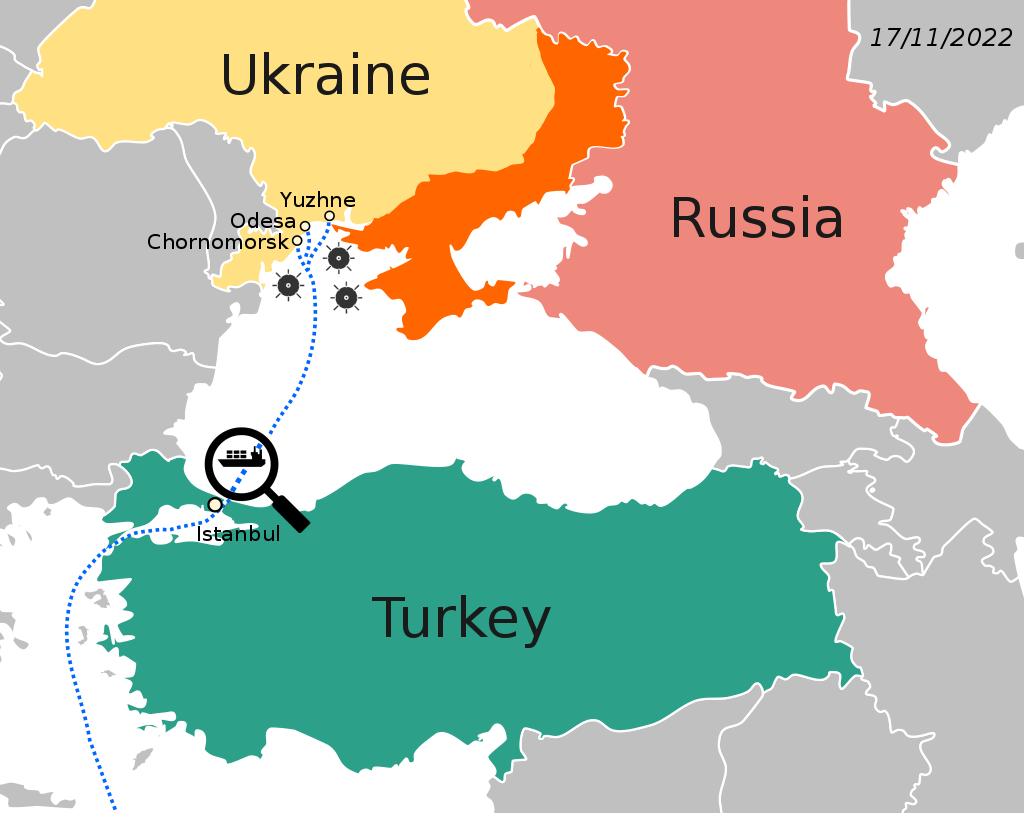

Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, exports of grains from Ukraine and food and fertilizers from Russia have been severely impacted. The disruption in supplies contributed to the global food crisis by driving prices even higher. In July of last year, the United Nations and Turkey established the Black Sea Grain Initiative to reintroduce vital food and fertilizer exports from Ukraine to the rest of the world. The contract was extended once in November for 120 days and then again on March 18 for only 60 days.

You can also read: Biden-Harris announces formal candidacy for 2024 Election

The agreement permitted the resumption of exports of grain, other foodstuffs, and fertilizer, including ammonia, from Ukraine to the rest of the world via a safe maritime humanitarian corridor from three critical Ukrainian ports: Chornomorsk, Odessa, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi.

The Ukraine has been able to export approximately 29 million tonnes of agricultural products, including 13.9 million tonnes of corn and 7.5 million tonnes of wheat, as a result of the agreement that created a safe shipping channel. This accounts for approximately 60% of Ukraine’s exports of grain during the current 2022/23 season and 56% of exports of wheat. In addition to rapeseed, sunflower oil, sunflower meal, and barley are also shipped.

Why Russia is threatening of leaving the deal?

Lavrov told reporters at the United Nations that one of Moscow’s demands involves having Rosselkhozbank rejoin the SWIFT banking system. Two days after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the United States, its European allies, and Canada moved to block critical Russian banks’ access to the SWIFT. The exclusion of Moscow from SWIFT, which stands for the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, severed the country’s ties to a significant portion of the global financial system.

Lavrov added that the agreement is presently imbalanced because Russian fertilizers have not been permitted the same transit rights as Ukrainian grain. “It was not called the grain deal it was called the Black Sea Initiative and in the text itself the agreement stated that this applies to the expansion of opportunities to export grain and fertilizer,” Lavrov told reporters during a press conference.

“That’s not the deal we agreed to on July 22,” he added.

The reconnection of the Russian Agricultural Bank (Rosselkhozbank) to the SWIFT payment system is one of the Western barriers Russia has insisted must be removed before any extension is considered. Other requests include allowing reinsurance and insurance services to resume, restarting the Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline, and allowing Russian enterprises involved in food and fertiliser exports to have access to their assets and accounts. The West shows slight indications of giving in to such demands.

In a letter to Russian President Vladimir Putin, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres outlined several options for extending the agreement, which Moscow claims will come to an end on May 18. Lavrov was unwilling to elaborate on the letter’s specifics but said that counterparts had been sent to Ukraine and Turkey.

Can the ports operate in future without Russia?

Prior to the treaty in July of last year, Ukraine’s ports were sealed, and it is unknown whether grain could be shipped if Russia left. Insurance premiums, which have become sky-high, would go up even further, and shipowners might be unwilling to send their vessels into an area of conflict without Russia’s blessing. Insurers would have to weigh the likelihood of damage due to things like Russian navy ships patrolling the Black Sea and floating sea mines.

After the war caused farmers in Ukraine to grow less corn and wheat, experts predict a drop in exports of grains for the 2023–24 harvest. But if the growing circumstances are good, the drop could not be as severe.

The International Grains Council predicts that Ukraine will harvest 21 million metric tons of grain, down from 27 million metric tons in the previous season, with exports falling to 15 million metric tons from 20.5 million metric tons. The number of metric tons of wheat produced in Ukraine is predicted to drop to 20.2 million in 2022/23 from 25.2 million in the previous season, with exports also expected to decrease to 11 million from 14.5 million.

Since commodities grown in the eastern regions of Ukraine have a lengthy and difficult journey just to reach the border, exporting huge quantities of grain through the eastern European Union would be both administratively challenging as well as costly.

Land routes are not feasible either!

Since the start of the crisis, Ukraine has been shipping large quantities of grain through eastern EU nations including Hungary, Poland, and Romania. However, there have been a number of operational hurdles, such as various rail gauges. Like other post-Soviet countries, Ukraine’s rail system uses a 1,520 mm gauge. The 1,435 mm gauge used by the countries of the Eastern European Union prevents trains from traveling seamlessly between networks.

Producers in the eastern EU are already complaining that the influx of Ukrainian grain has damaged regional supply, been bought up by factories, and left them without a market for their production.

The global food price issue has been worsened by decreased exports from key exporter Ukraine. The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and climatic extremes are two more contributing reasons. Closing the corridor would cause a spike in global grain prices at a time when many countries are already struggling to meet rising demand for imported food and fuel.